Efficient Markets = Average of All Inefficient Investors | Finance Papers Part 1.3

Eugene Fama dropped a bomb on Economics & Finance in 1965, and we've been picking up the pieces ever since. If you've ever wondered what it means to have something "priced in", read this post.

Have you ever heard of some piece of news or information being “priced in” or, more recently, not “priced in”? The news could be a macroeconomic event like GDP growth figures, war breaking out, or an expected slow down in the increase of interest rates. The news could also be company or industry specific: Apple cutting iPhone orders or Target overstocking inventory.

In our world, we take it for granted that asset prices reflect all available information. But is this core belief true? If so, what are the implications? What’s the purpose of the capital market? What is the value we should place on information? To find the answers, we’ll explore the expansive work of Eugene Fama on the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

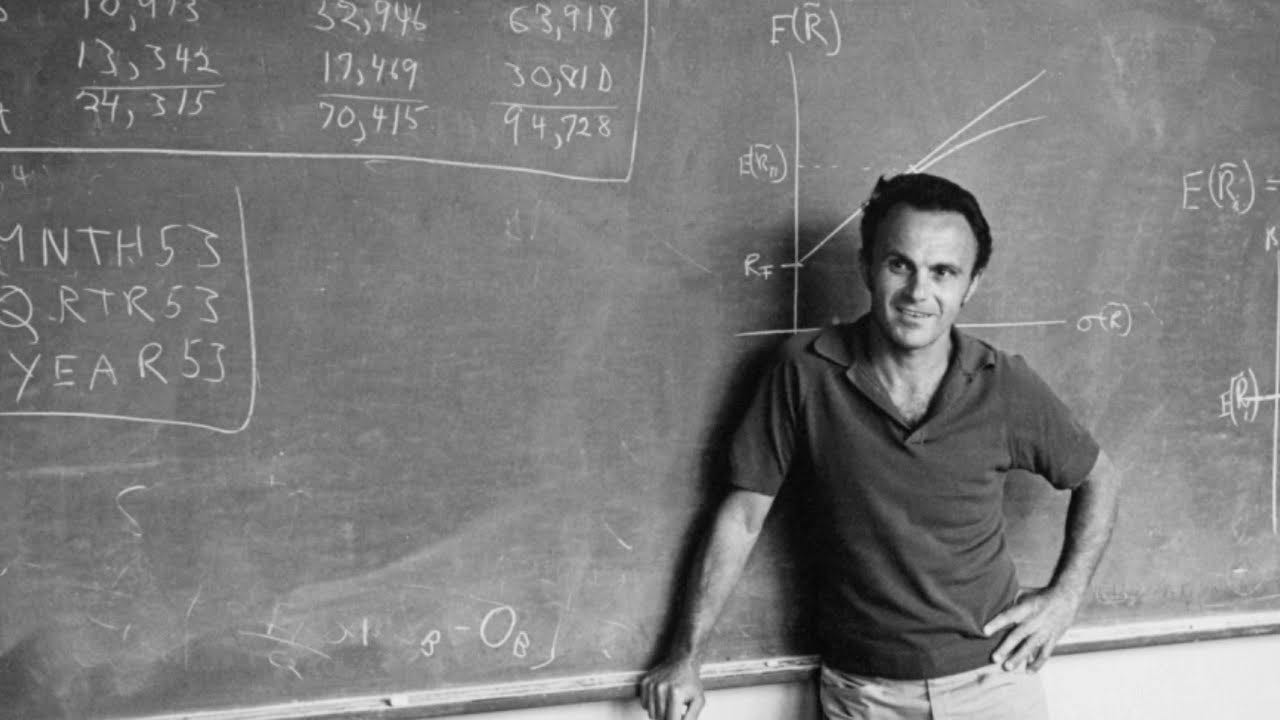

No pair of papers have divided modern financial economics more than Eugene Fama’s 1965 “The Behavior of Stock Market Prices” and its 1970 follow-up “Efficient Capital Markets”. The second paper has +36,000 citations whose reason for citing ranges from treating EMH as practical fact to showing the hypothesis has impossibly flawed logic.

It certainly doesn’t help with cohesion that the 1970 paper leads off with breaking EMH into three forms: Strong, Semi-Strong, and Weak. In the next post, we’ll cover what each of these mean as well as their implications.

And yes, I did say “next post”. Unlike Markowitz and Sharpe, trying to pinpoint Fama’s contributions to one paper is difficult. His impact spans multiple decades with major works being published in every decade since 1965.

Rather than try to cram nearly a decade of output into one post, I’ll be breaking this up into three posts:

The background and key points of Fama (1965)

Fama’s research from 1965-1969 which culminated in Fama (1970)

The lasting reception of EMH

With that out of the way, let’s dive into how an English Botanist, French Mathematician, and the man whose “life seemed to be a series of events and accidents” led to the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

Floating Dust & The Origins of Efficient Markets

The origins of markets being “efficient”, that is having prices which reflect all available information, begins, like everything in this world, with things floating in water — sorta.

In 1827, English botanist Robert Brown, credited with discovering the cell nucleus, described the jittery, random motion of particles suspended in water but made no attempt at modeling the mathematics underlying the motion. The math behind it would then sit on the shelf of unsolved phenomenon for another 73 years, before making a reappearance in a field far from botany.

French mathematician Louis Bachelier took on the challenge in his 1900 doctoral thesis (Original French, English) which covered market speculation. The thesis is now considered the first finance paper to utilize advanced mathematics and is the earliest reference to what we would now call the “Efficient Market Hypothesis”:

It is obvious that the price considered by the market as the most likely is the current true price: if the market thought otherwise, it would quote not this price, but another one higher or lower.

The idea was far ahead of its time, and it would fade into history until 1955, when Leonard Jimmie Savage dusted off Bachelier’s work and began asking if anyone had heard of this theory before — no one had, but mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, of Mandelbrot set fame, was happy to read more.

Random Walks to the EMH

Mandelbrot & Random Walks

Benoit Mandelbrot was “a powerful, original mind that never shied away from innovating and shattering preconceived notions” and “an icon who changed how we see the world.” His pioneering work covered fractal geometry, information theory, and (most importantly for us) financial economics.

In the last field, his most important written contribution to Fama’s work came in a series of papers on the randomness of stock market returns. In these papers from 1960 to 1966 Mandelbrot proves that…

Returns of a stock follow a “random walk”: that is, they are randomly distributed and independent of previous returns;

fundamental value is based on all available information;

market value cannot maintain an over-(under-)pricing relative to fundamental value; and

stock returns are not well explained by a Gaussian distribution, instead having fat-tails (they’re leptokurtic).

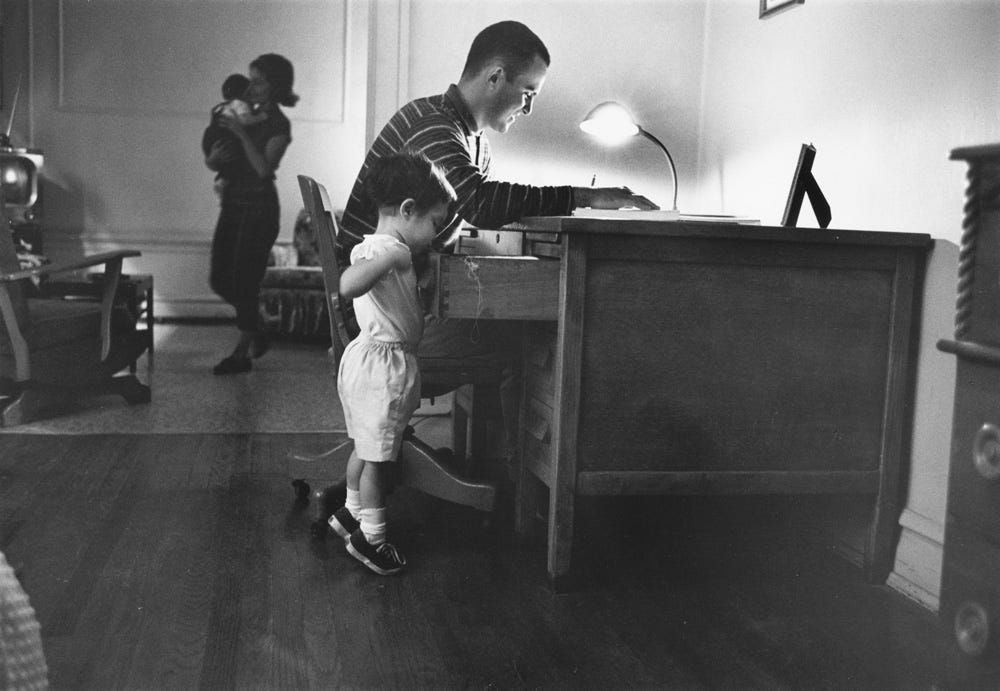

Mandelbrot’s most important overall contribution to Fama’s work, however, came while Fama was a graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1961. Mandelbrot was an occasional guest lecturer for one of Fama’s courses, and the two struck up what became a lifelong friendship.

The two would often consult with one another while taking “leisurely strolls” around the campus. It was on these strolls where Mandelbrot introduced Fama to fat-tailed probability distributions and his theories of stock market returns, culminating in Fama’s 1965 thesis paper proving, “in nauseating detail,” Mandelbrot’s assertion that stock returns are fat-tailed.

The Birth of the Efficiency

The same year his thesis was published, Fama would formally define “efficient markets” for the first time as “a market where there are large numbers of rational profit-maximizers actively competing, with each trying to predict future market values of individual securities, and where important current information is almost freely available to all participants.”

Again there is this assumption of rational, profit-maximizing investors which has carried since Markowitz, but now it has been combined with the idea current information is being used to predict future values. Rather than restate it, I’m going to quote Fama at length (emphasis is mine):

In an efficient market, competition among the many intelligent participants leads to a situation where, at any point in time, actual prices of individual securities already reflect the effects of information based both on events that have already occurred and on events which as of now the market expects to take place in the future. In other words, in an efficient market at any point in time the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of its intrinsic value.

Here we see Fama building again on the ideas from Mandelbrot: Intrinsic Value (sometimes called “true price”) and Market Value should be about the same, given that actors are rational and act on all available information. If prices were exactly correct, then they would only move when new information reaches the market, but instead we see prices continuously fluctuate.

Why do they fluctuate if the information is reflected in the price? Fama addressed this as well:

Now in an uncertain world the intrinsic value of a security can never be determined exactly. Thus there is always room for disagreement among market participants concerning just what the intrinsic value of an individual security is, and such disagreement will give rise to discrepancies between actual prices and intrinsic values. In an efficient market, however, the actions of the many competing participants should cause the actual price of a security to wander randomly about its intrinsic value.

In aggregate, the wisdom of the crowds will prevail, but because the future is uncertain, investors may continuously update their assumptions about the future, causing fluctuations around the mean. The goal of investors is to maximize returns, but is it possible to do better than the market? Yes, but not for very long…

If the discrepancies between actual prices and intrinsic values are systematic rather than random in nature, then knowledge of this should help intelligent market participants to better predict the path by which actual prices will move toward intrinsic values. When the many intelligent traders attempt to take advantage of this knowledge, however, they will tend to neutralize such systematic behavior in price series.

This paragraph will come back in the 1970 paper where it will define the different forms of market efficiency. It also contains a key nugget for refuting investors who deny the validity of EMH:

Some investors are clever enough to out perform the market, but many are not.

If you average the performance of investors over time, you’ll see outperformance fades away leaving you with the market return.

To summarize several key points from Fama’s 1965 paper:

The intrinsic price of a stock is the price which reflects all available information in the market

Prices fluctuate around the intrinsic price due to trader’s disagreements about the future

New information is very quickly reflected in the price of stocks

But does reality prove this to be true? Turns out Fama had the same question. To answer it, he spent the next 4 years conducting a groundbreaking event study to see whether his new idea held up in the real world. In 1969, Fama would publish FFJR: the opening salvo in the fight to prove EMH.

Two quick programming notes:

After wrapping this set of posts, I’ll be taking a little break to research and plan the posts for Behavioral Economics.

This style of post is likely to be repeated again later on — first that comes to mind are the works of Michael Jensen — one of Fama’s frequent collaborators.

A sneak peek at the next post:

Event Studies and the Proof* for EMH

Fama’s 60+ years of impactful output began in 1965. Fama, however, was just getting started. The following 5 years saw a string of papers coming out of U Chicago and MIT, culminating in two classics of economics:

"The Adjustment Of Stock Prices To New Information", Eugene F. Fama, Lawrence Fisher, Michael C. Jensen, and Richard Roll (1969)

“Efficient Capital Markets”, Eugene F. Fama (1970)

These papers helped catapult EMH from just another idea in academia about markets to a fundamental topic which has defined careers for generations of economists. Before this could happen, Fama would need to prove (or at least not disprove) that EMH was valid.

Enter the true hero of our story: the event study.

Additional Reading

Shared with Author’s permission: Trump Tweets and The Efficient Market Hypothesis, Jeffery A. Born, David H. Myers, and William Clark (2017)

“Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH): Past, Present, and Future“, Gili Yen and Cheng-few Lee, (2008)

“History of the Efficient Market Hypothesis”, Martin Sewell (2011)

“The (Mis)Behavior of Markets”, Benoit Mandelbrot (2006)

Nobel Prize Lecture, Eugene Fama (2013)

Samuelson vs Fama on the Efficient Market Hypothesis: The Point of View of Expertise

"The Fama Portfolio" by Ray Ball, 2017

Extra Bits

Bachelier does not deny that there is irrationality, just that it does not persist and reverts to the mean:

On the other hand, it is undeniable that the market has had, for several years, a tendency to quote spreads that are too great for options with short terms to expiration; it takes even less account of the correct proportion of those spreads that are smaller and for which the expiry date is very close. However, it must be added that the market seems to have realized its mistake, because in 1898 it appears to have been exaggerated in the opposite direction.

Bachelier actually beat Einstein to the equations explaining Brownian motion by 5 years. Where Bachelier would use it to explain stock price movements, Einstein would use it to explain the nature of the atom as part of his “Miracle Year”

Milton Friedman, when asked about Jimmie Savage, described him as “one of the few people I have met whom I would unhesitatingly call a genius.”

Fama (1965b) describes what we now call “alpha decay” — the speed at which new market information is reflected in the prices of securities — and is the main reason that high-speed trading firms are willing to spend over $300 million to shave a few milliseconds off of their trade times.

Fama’s 1969 paper was co-authored with Michael Jensen (who we’ll talk about in the 1980s economics section), Lawrence Fisher (a cofounder of the CRSP stock database), and, possibly the most interesting person I’ve come across so far, Richard Roll.