How to Start a Fintech

All it takes is finding the right market, using some new(ish) technology, and a whole lot of hustle: in 1967, George Thorpe managed all three.

For the last 3 years, I have been enamored with the story of a boring and clever fintech company. The hook was the year long struggle to buy its first computer — not generate its first sale but acquire the means of generating any sales. The deep end really begins when looking at the moment in which National Data Corporation came into existence.

Before hiring employees or buying computers, Col. George W. Thorpe left his job as a railroad executive with little more than an idea. It had been itching in the back of his mind for over a decade. He saw a way of connecting people and data to solve problems using the best technology of the era, and for him 1967 had the perfect intersection of a need for data and the technological advancement to apply his idea.

After 5 years in operation, his idea, the National Data Corporation, would come to dominate 65% of its market. This degree of market share is something that many fintechs today can only dream of. So how does someone start a successful one in 1967? Or 1998, 2010, or today?

Find a problem serving a niche market or ‘boring’ customer (ideally both)

Borrow an idea from somewhere else to solve the problem

Sell the dream (and find a buyer)

The Problem & The Customer: Trust & Communication Speed Prevents Trucking Company Fleet Cards from Wide Acceptance by Fuel Stations

In the 1950s and 1960s interstates were being paved across America opening the door to regional and even national trucking operations. Thanks to this, the trucking industry went from delivering within a few counties or states to routes which covered regions and even drove coast to coast. This brought a major challenge: how to pay for all the fuel?

Initially, trucking companies could rely on cash carried by the drivers or arrangement with nearby fuel stations (key cards or gas tabs). But as routes and trucks grew, so did the demand for a more robust system. This need led to trucking partnering with the major oil companies to create “fuel keys”.

The keys were inserted at special pumps which would tally the gas used by each company. This total would then be billed to the trucking company each week. But what if you didn’t have any stations on your route or needed to make an emergency fuel stop? Thankfully, the banks were ready to step in with a brilliant idea: Fleet Cards.

A Fleet Card is like a credit card but is limited to purchases at fuel stations, maintenance shops, and certain types of convenience stores. When introduced, a gas station clerk would take down the card details on a slip and mail it to the issuing institution. The list was checked by the issuer and paid based on transactions made by valid cards.

The manual processing and long delays between sale and settlement combined with high processing fees — the interchange was as high as 8% — meant transactions were expensive for stations to process. This made stations less keen on accepting cards, thus limiting their spread.

The door was open for a clever business with the help of new technology to solve a niche, very tangible issue (instant fleet card verification) for customers who have been offering the same service for over 60 years (and now over 120). But no technology had been invented to solve this problem at the time, so an entrepreneur would have to look outside of financial services for a solution.

While stationed at Offutt Air Force Base in the heart of oil country and later as a railroad executive, Col. George W. Thorpe got a taste of the problem, and his work with SAC intelligence data showed him what a possible solution might look like.

The Borrowed Ideas: Real-Time Airline Reservations

Following World War II, the shrinking of transistors and semiconductor chips gave rise to the revolutionary mainframe computer. Mainframes were at the leading edge of technology for the time and represented a chance to automate many business functions (receptive, clerical, or number crunching tasks) in a way very similar to how AI and Cloud Computing are pitched today.

After the expensive punch card led 1950s, the next wave of mainframes came in the 1960s as costs came down +40%, processing speed increased ten-fold, and computing moved away from punch cards and toward real-time processing using monitors and keyboards. The most enthusiastic adopters of this new wave of computing were airlines and financial institutions who saw the benefits of having quick access to records.

Airlines of the 1960s faced a scale issue when it came to booking a passenger:

Reservations agents were free to book space on a flight after confirming seat availability posted on large display boards in each reservation center’s office… Upon receipt of the booking message, a clerk decreased the count of available seats for the flight from an inventory maintained in a looseleaf folder.

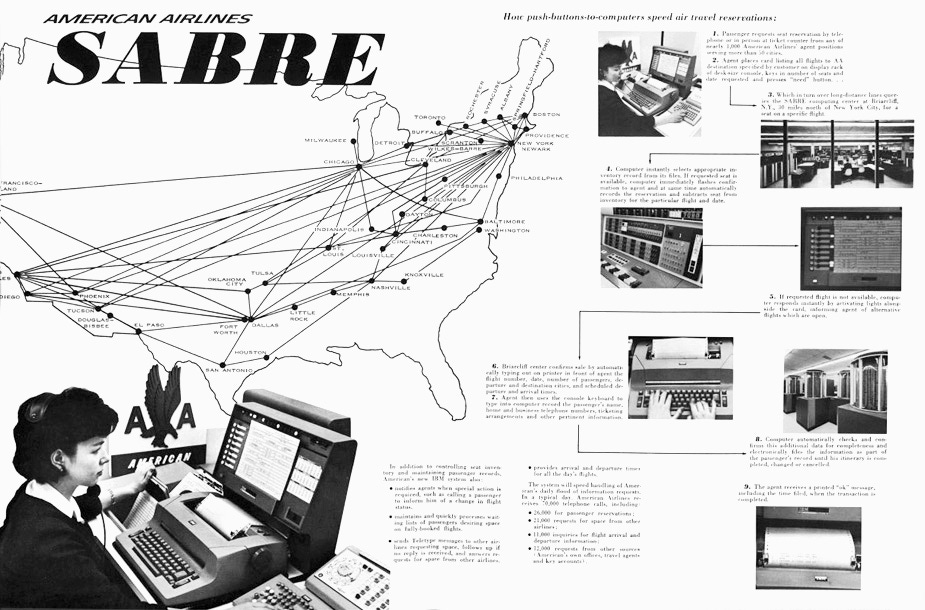

This created a lot of under/over-booked flights, potential for confusion, and a painful customer experience. To solve it, American Airlines entered a decade-long collaboration of IBM to launch Sabre: the first electronic airline reservation system.

It worked by giving reservation agents a terminal which was connected via phone lines to a central mainframe computer. Inside the computer’s memory were the flight records and passenger data for each flight within American’s network. Any of the 1,100 agents across the country could key in certain information and within 30 seconds view, create, or modify a passenger’s itinerary. This was a massive leap forward compared to the 90 minutes needed in the previous punch card system.

In Sabre, IBM had created the world’s first commercial online transaction processing system — exactly what the team needed.

The Pitch: Instant Authorization

(Ret.) Col. George W. Thorpe had just wrapped up a successful 25 year career with the U.S. Air Force, landing an easy job as a railroad executive. He had years of experience leading cutting edge data processing at Strategic Air Command (SAC) — the backbone of America’s Cold War defenses — and it took him no time to tire of the railroad life.

So he turned back to his experience working with SAGE and data processing centers while Deputy Director of Intelligence. The U.S. Military’s SAGE defense system was codeveloped with American’s Sabre by the same IBM team and shared the goal of real-time data processing. These centers allowed for data to be input from a multitude of sources before being processed in a central location and sent out to offices around the world.

Thorpe quickly severed ties with the railroad and called UNIVAC, a cheaper IBM competitor. He explained his plans and asked what it’d take to get a hold of their newest real-time computer. They told him it’d take $1.5 million before they’d send him anything, so he did what all entrepreneurs must eventually do: he started looking for investors. After “couple of pairs of shoes,” Col. Thorpe finally received a check from investment bank Robinson-Humphrey based on his idea:

A station owner anywhere in the country could call National Data and be connected to one of 4 regional communication centers. These centers would be connected to a central UNIVAC computer in Atlanta by the phone lines. Within 20 seconds an operator would be able to enter the card information and let the station owner know whether the card was valid.

For issuers, Built into the card verification is a bonus “early warning” feedback on suspected fraud. Amounts reported at each verification are stored in the computer. Should purchases exceed preset limits, the company issuing the card is notified so that it can check for a possible stolen card.

With a check in hand and contracts with a Mobil Oil in place, Col. Thorpe sent a short message over to UNIVAC…

‘We have the money. Please send the damn computer.’

There’s no right time to start a fintech — or any business — or launch a new offering for an established business. If you understand the problem you’re trying to solve and who you’re trying to solve it for, then you can look for inspiration anywhere.

The hardest part is selling the dream to investors and getting buy-in from stakeholders. If you’ve done the first two steps right, the sound of customers knocking down your door should be enough. If that doesn’t work, wave a check in the stubborn party’s face and tell them “please do the damn thing.”

Supplementals

I wrote these because I needed a space to put all of the extra information accumulated on my journey. Leaving it behind felt like a waste, so enjoy!