Economics of Payments

People and Businesses send money in a variety of ways - each of which comes at a price. As emerging payment rails like Venmo and CashApp grow, who will foot the bill?

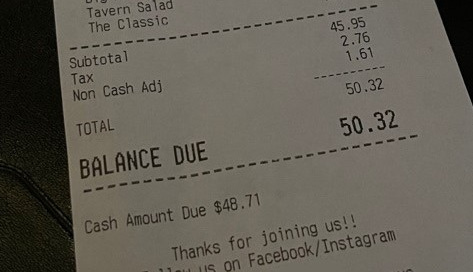

One of my friends recently had a “non-cash adjustment” applied to his bill at a restaurant and asked me why a business would penalize its customers for not using cash. The answer is closely related to why Amazon is planning to stop accepting Visa credit cards next January.

Unlike Amazon — whose sheer scale is enough to make a sizable dent in Visa’s profits — this restaurant is choosing to pass the interchange fee onto consumers. Which ultimately just makes the credit card network, the merchant and acquiring banks more money…

$48.71 <- "Cash Amount Due"

$ 1.61 <- the Merchant Interchange Fee calculated on $48.71 bill

$50.32 <- Bill total

$1.61 / $48.71 = 3.3% <- % Interchange Fee per transaction

$50.32 * 3.3% = $1.72 <- Interchange fee on new transaction

($50.32 - $1.72) - ($48.71 - $1.61) = $1.50 <- Restaurant's additional profit

$1.72 - $1.61 = $0.09 <- additional interchange revenueThis works for credit cards because its economic model is a function of transaction ($) value, but what about other payment methods? Who pays and how is it calculated? Let’s take a look at the three most common payment economic models:

Value ($)

Volume (#)

Variable (demand-based)

Let’s dive in and see what it means for you and me, businesses, and the future of payments.

Before we begin, I think it’s important to state a few definitions to understand the jargon:

Payment rail ~ payment network

“Economics” in this context is a business school euphemism for fees

Settlement = when the obligation between payer and receiver is satisfied

Availability = when the receiver of the payment can spend the funds

Cheque = paper check (helps to avoid confusion with “check” the verb)

Value-Based Economics

Credit Cards, Debit Cards*, PayPal, and “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL)

In the intro, we walked through the canonical example of value-based economics as it relates to credit cards. Assessing a percentage of the transaction value is a practice at least as old as coinage and can be argued to extend all the way back to the agricultural revolution.

Value-based economics exist because of an underlying credit (time between the transaction event, availability, and settlement) built into the payment network as well as the convenience that the rail offers senders and receivers.

Extending credit necessarily carries risk, so it follows that the greater the amount of credit, the greater the risk. The History of Risk shows us that those who extend credit require compensation — think interest on loans and, in our case, fees for payments.

The magnitude of convenience a payment rail offers (as well as the degree to which it’s treated like a commodity) determine who pays and how much they pay. In the early days of credit cards, both the merchant and consumer paid fees to use the network.

With the exception of premium credit cards, consumers no longer pay to simply own a credit card because it’s become a commodity item — to the point where issuers will pay you to get a card. Businesses, however, still benefit from increased order sizes (in theory), so they continue to eat the interchange fees.

The fee itself varies by the size of the merchant and card network, but a general rule of thumb is 1.5 to 2.5% — though this has been declining in recent years as providers like Square and large merchants like Amazon push back. PayPal is similar in structure with 2 to 4% of the transaction, and BNPL, which boast a order sizes +60% higher than credit cards, has fees of 4 to 8%.

Debit cards, until recently, had an unregulated interchange fee. This changed in 2012 with the passage of the Durbin amendment which fixed interchange fees for debit cards at 0.05% plus $0.22 for each transaction. Given the average $36 debit transaction, the interchange fee would be $0.24 ($0.22 + $0.018). This is why I’ve included it in both the Value- and Volume-based categories, because you’d have to spend $20 to hit 1 cent in variable fees.

Volume-Based Economics

Cheques, ACH, Wire, Debit Cards*

Volume-based economics are found on most institutional payment rails. This includes ACH (how +80% of Americans receive a paycheck), Wire (how most remittance payments are made), and cheques (how a 81% of B2B payments are made).

These networks are robust, but, unlike the payment rails in value-based economics, require the sender and receiver to have a degree of trust — you have to have the other party’s bank account number to complete the transaction.

As you can see in the table above, volume-based rails fee rates are based on the speed of the transaction and are paid by whomever stands to benefit the most from the transaction.

Cheques and ACH Debit (think online bill pay, where a company pays itself from your account on your behalf) are of the most benefit to the recipient of the funds. ACH Credit (a company sending payroll) and Wire transfer are charged to the sender because they owe the obligation — with Wire yielding a much higher fee due to its same day speed.

These payment methods are the backend to almost every other payment rail:

Digital wallets (Venmo, CashApp, Crypto exchanges wae) are loaded from bank accounts via ACH

Credit card transactions are ultimately settled between the merchant and acquiring banks via ACH or Wire

Variable (Demand-Based) Economics

Bitcoin, Ether, & other Cryptocurrencies

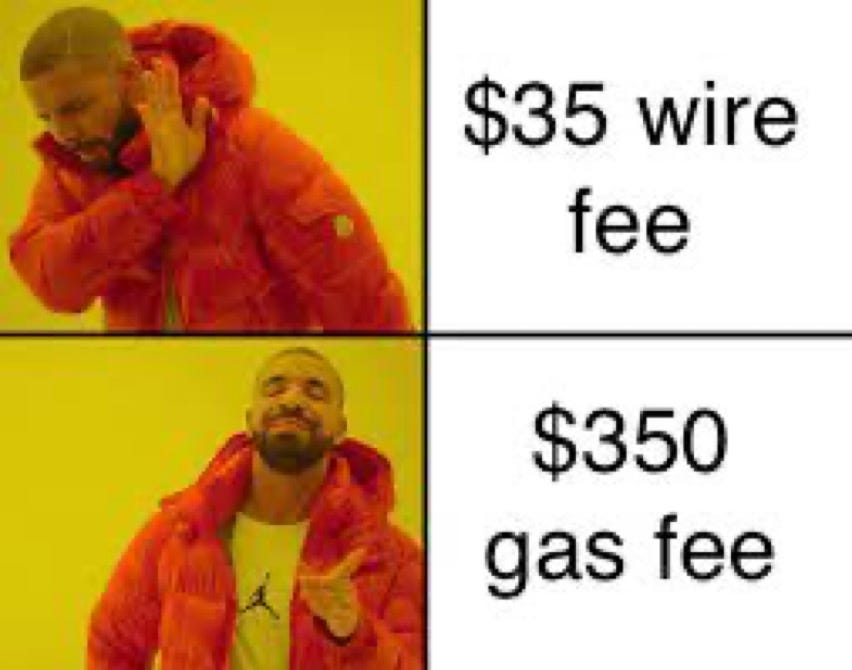

Transaction fees for cryptocurrencies are demand driven given the nature of the public ledger. The fees are set by people looking to make a transaction and miners select the transactions with higher gas fees to process first. In periods of particularly high transaction demand, the processing of transactions takes increasingly large amounts of time, effort, and energy for which the minders are compensated with higher fees.

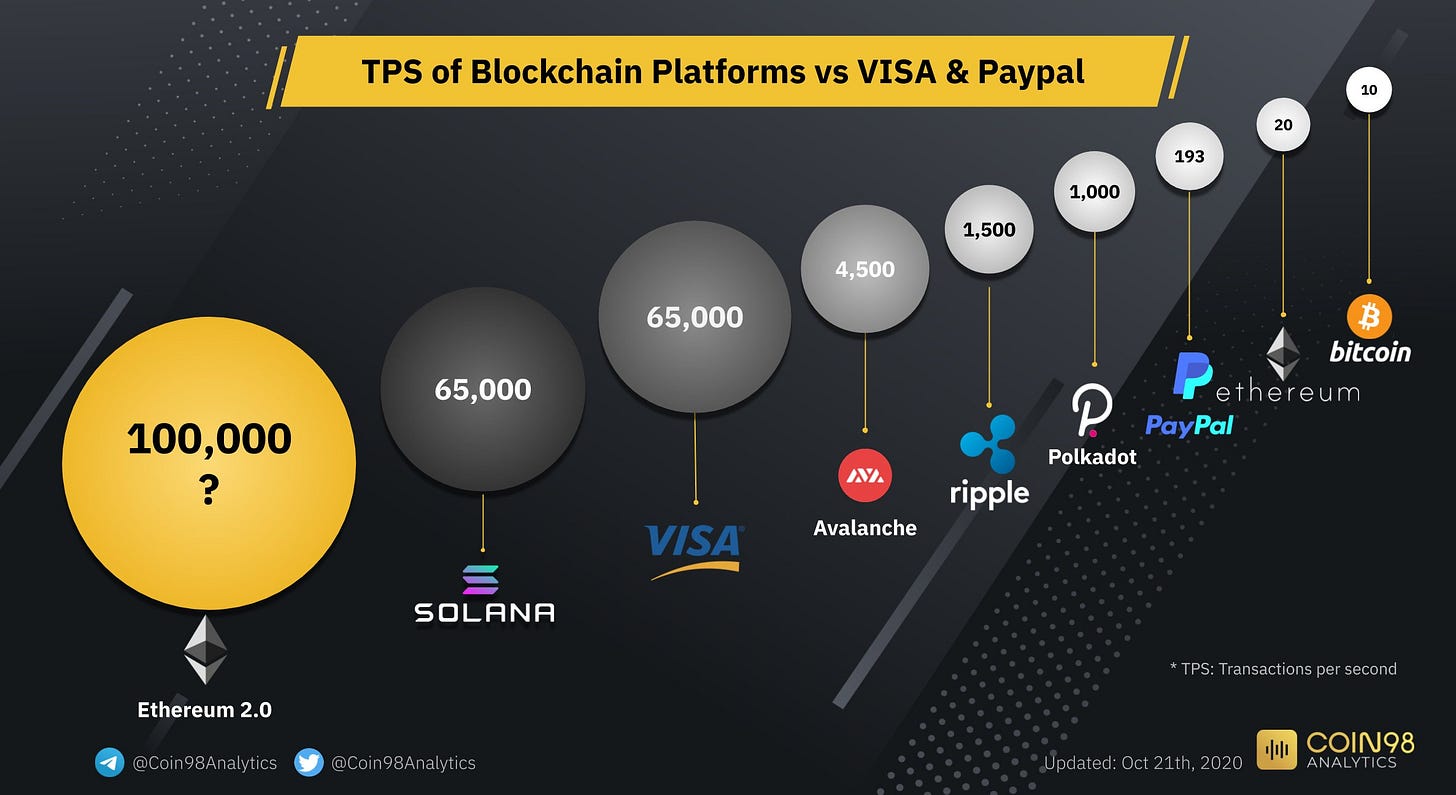

The variable nature of fees combined with the comically low transactions per second of Bitcoin (10) and Ethereum (20) have made it an unsuitable replacement for Visa (65,000) or PayPal (193).

Solona and Ethereum 2.0 seek to solve this issue through more efficient processing, but that’s beyond the scope of today’s piece.

So what can we expect for emerging payment rails?

P2P Networks (Zelle, Venmo, CashApp) are the frontier of payment rails. For now, they’re free for you and me, but will it always be that way?

P2P networks ultimately monetize by becoming C2B networks. Plain and simple.

Average users will not pay for a service unless the perceived benefits far outweigh the cost: meaning that the networks have to achieve critical scale of clients and transactions volume before monetizing it by charging businesses.

Venmo is already doing this! Charging 1.9% + $0.10 for payments made from Venmo funds and 3% for payments funded by a credit card through Venmo!

Think of it like Facebook: Always free for users, but charges advertisers for access to your eyeballs (digital wallets).

Until crypto or CBDC can figure out the variable transaction fee model, it seems we’ll just keep seeing more of the same old.

Further Reading

Debt: The First 5,000 Years (Talks @ Google, book)

Card Network Fee Overviews (page 4)

See you December 5th!

-Wilson