Embedded Finance Worked for GE - Until It Didn't

What GE can teach Apple, Amazon, and Starbucks about the highs and lows of embedded finance.

How do you sell expensive washing machines in the Great Depression? Offer in-house financing. This simple insight launched one of the most powerful financial engines in corporate history: GE Capital. While it started as a tool to boost product sales, it ended as a cautionary tale for every non-financial company chasing the allure of financial returns.

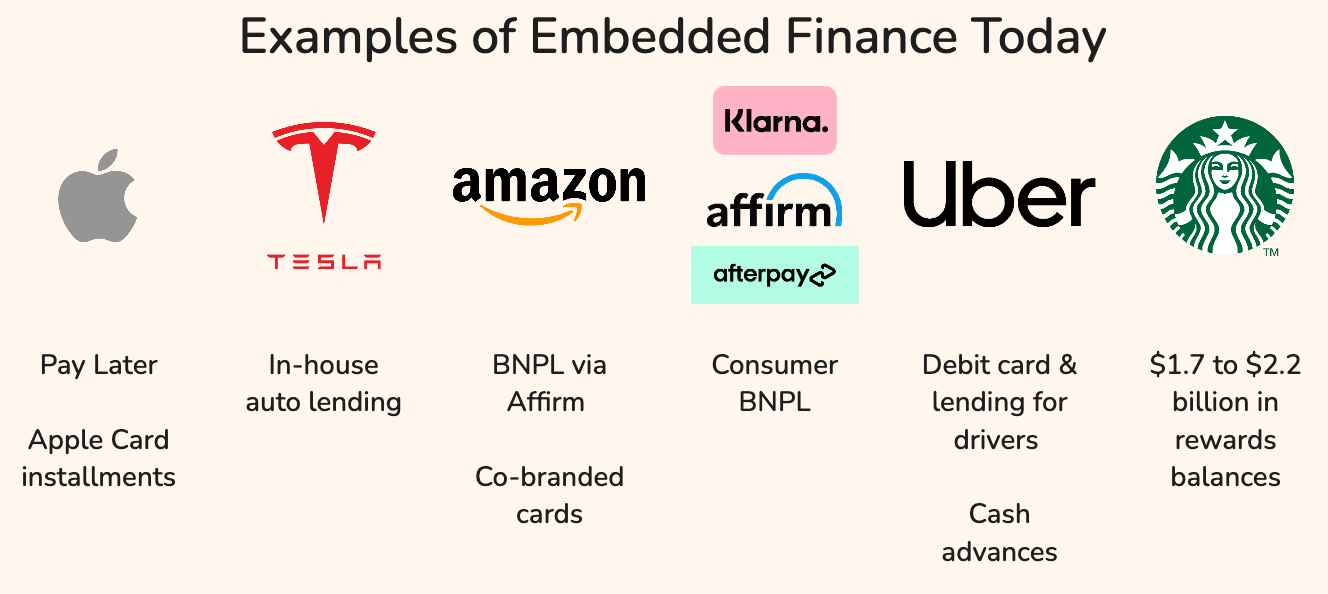

Today, embedded credit is back in vogue. Apple, Tesla, MercadoLibre, and Amazon are offering credit at checkout and spreading payments over time. Embedded lending — a subset of Embedded Finance — played out great for GE…until it didn’t. What remains to be seen: will today’s companies learn from past mistakes.

From Washing Machines to “One of the biggest names in almost everything”

General Electric (GE) was the 20th century darling of American manufacturing. Founded in the 1880s by Thomas Edison and Charles Coffin1, GE played a role in innovations that defined the era from 1900 to 1960 — mostly in consumer appliances, electronics, and aviation. Take a look in your kitchen and you’ll find light bulbs, toasters, ranges, and dishwashers based on designs pioneered by GE.

The most impactful innovation was the washing machine, with their first model being released in 1930. One study found that households with a washing machine saved more than 3 hours per week — nearly 7 days a year.2 There was only one problem: the country was in the throws of The Great Depression.

With wages, consumer spending, and confidence at all time lows, the market simply couldn’t afford to save the money needed to purchase an appliance that cost several months wages. To increase sales, another type of innovation would be needed.

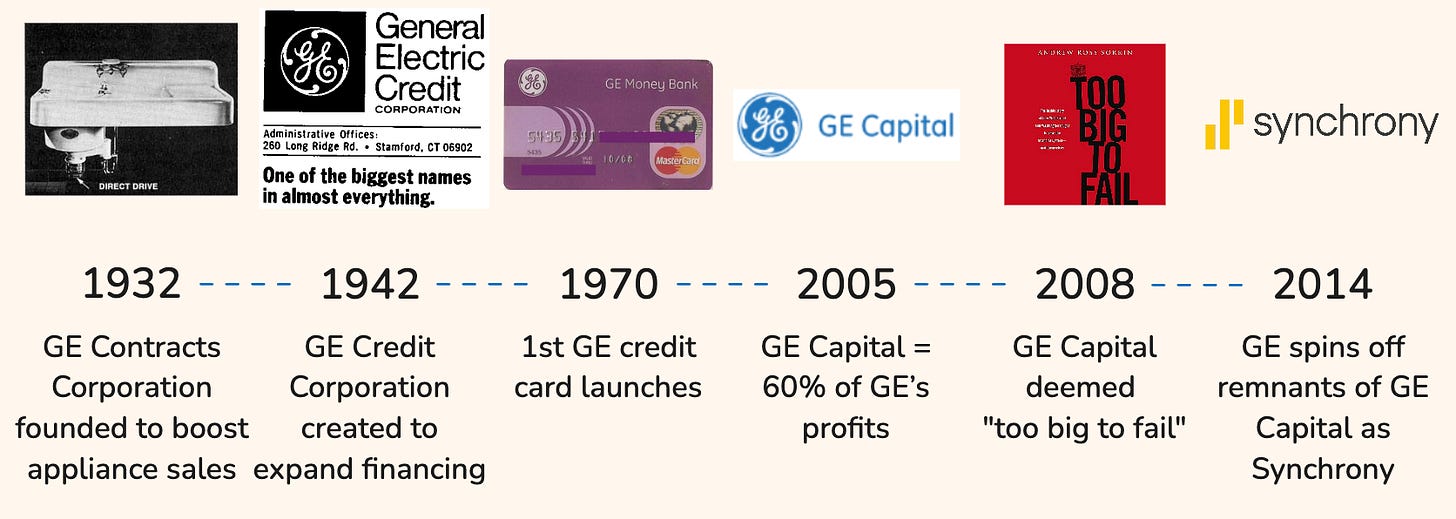

Established in 1932, the General Electric Contracts Corporation was created to provide financing solutions directly to GE customers in the form of installment plans. It was intended to make GE’s products more accessible and stimulate demand. Customers flocked to GE and similar services from Sears and Ford, to stretch their dollars and acquire modern tools in a time of economic uncertainty.

GE Contracts Corporation was so successful that GE expanded its scope to include industrial and commercial financing in 1942 during the height of WWII. GE Credit Corporation (GECC, later GE Capital), went beyond simple installment products to include loans, lease financing, and real estate financing. Then in 1970, the GE Credit Card was introduced, hopping on the trend of retailer-specific cards — an early form of “private label” credit card.

Private label cards locked customers in — an early version of ecosystem finance. In the 1970s, around 50% of households had a credit card, and the majority were private label rather than the “general use” cards we’re accustomed to today. This was intended to drive sales and keep customers in the company’s ecosystem — something that was easy to do in the age of conglomerates. It proved to be an addictive source of profit for GE from the 1980s onward.

Under CEO Jack Welch, who started in the line of business, GE Capital would become the core driver of GE’s overall profitability; the seventh largest bank in the US; and the largest private label issuer with a +40% market share. When the financial crisis of 2008 hit, GE was forced to write-down or write-off most of its lending portfolio. As part of the aftermath, GE Capital was partitioned and sold off to various parties. One of these is Synchrony Financial, still the largest private label credit card issuer in the US.3

What to learn from GE Capital’s meltdown?

GE didn’t set out to become a “too big to fail” bank. It just wanted to sell more products. But the success of embedded credit became so powerful, it transformed the company’s identity—and ultimately its risk profile. As time went on, GE became reliant on GE Capital to smooth returns and stay afloat:

Under the leadership of Jack Welch, GE Capital grew to be a reliable contributor to the parent company bottom line — contributing nearly 60% of GE’s overall profits at its peak. GE Capital had a reputation for providing consistent, predictable, reliable earnings; nipping and tucking as needed and managing — read this as manipulating — the parent company’s quarterly results.4

Ultimately, GE Capital was (rightfully) deemed a systemically important (“too big to fail”) financial institution. Rather than deal with the increased regulatory scrutiny, GE sold off GE Capital at the beginning of 2014. The brand would be renamed Synchrony Financial — still one of the largest private label cards in the country — and with that the 82 year run of GE Capital came to an end.

How to Adapt to Embedded Finance Today

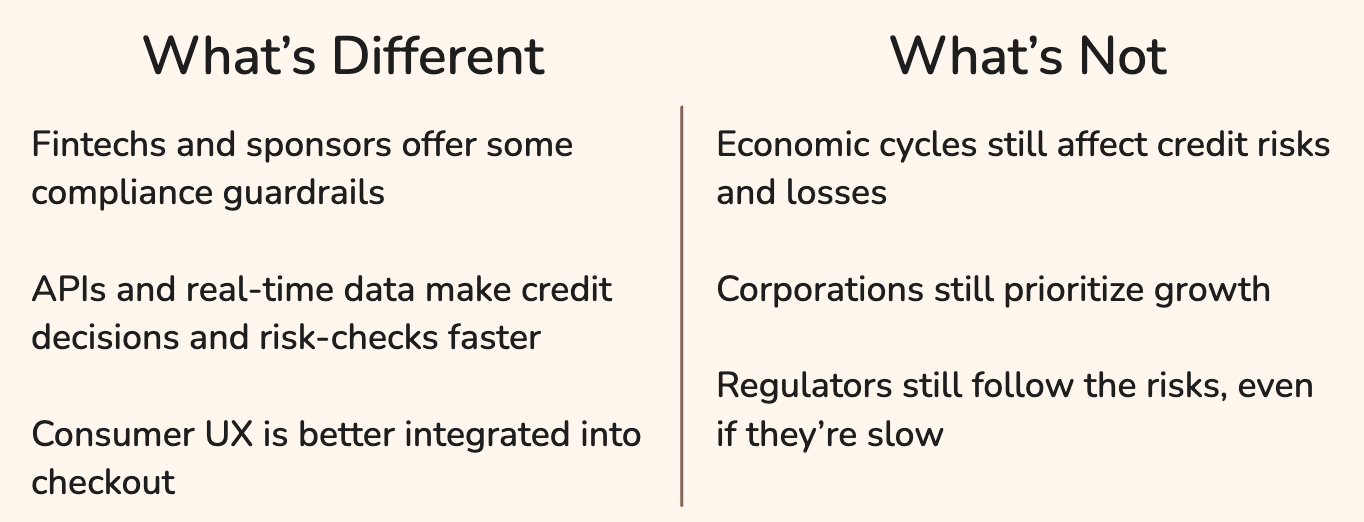

The lesson in this is that non financial corporations are often not the best stewards for financial services. The underlying profit motive and desire for strong, consistent returns often runs counter to the risk management practices needed to run a financial institution. If the 2008 financial crisis is anything to go on, even some of the largest financial institutions can be ill equipped.

Like GE, today’s companies aren’t setting out to become banks — they’re trying to sell more products, keep customers loyal, and improve conversion at checkout. But, as GE showed, that growth lever can become a crutch. They’ve got to make sure that finance is the lever, not the endgame and learn the lessons GE Capital offers.

Lesson 1: Easy Credit Can Be Addictive

GE’s core business increasingly relied on GE Capital to hit earnings. Lending and financial engineering became more profitable than the core business (manufacturing). Then when credit markets tightened, it destabilized the entire company. Companies using lending or embedded finance as a lever to fuel expansion need to temper the desire for growth with prudence.

Example: Tesla offers financing to help sell its cars, and Apple’s interest-free installment plans drive iPhone sales. But what happens when interest rates rise, credit losses spike, or consumer spending slows? Today, companies like Apple and Tesla use embedded lending to smooth product sales. But the danger is the same: when credit markets tighten, those sales may vanish—and so might profitability.

Lesson 2: Corporates Aren’t Built for Credit Risk

Traditional banks are built around risk management: capital buffers, underwriting discipline, and long-term stability. Corporations, on the other hand, are usually set to prioritize growth and shareholder returns. GE was great at engines, not at managing systemic financial risk. Embedded lenders today are mostly tech companies.

Example: Klarna expanded aggressively during the low-interest rate era, but as rates climbed, its valuation dropped from $45 billion to $6.7 billion in a year. Companies integrating finance must ask: are they building a sustainable credit business, or just using easy lending to boost short-term sales?5

Lesson 3: Regulation Eventually Catches Up

GE Capital was eventually labeled systemically important and regulated like a bank. That spelled the beginning of the end. Now, the CFPB is classifying BNPL as a form of credit. Embedded finance players like Apple, Uber, and Affirm are expanding financial services without banking charters. These companies may find out the hard way that financial convenience comes with regulatory scrutiny.

Example: If Apple Card, Apple Pay Later, and Apple Savings reach scale, regulators may question whether Apple is a tech company or a financial institution. Will the company be ready for that level of oversight?

Closing Thoughts: Is It Different This Time?

GE introduced embedded finance to sell more washing machines — not to become a bank. But the more successful it became, the more it lost its core identity. Today’s tech giants are echoing the same play.

Regulations introduced after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis introduced safeguards meant to prevent this identity drift. Most companies now turn to third party financial services providers like Affirm, Railsr, Marqeta, or Green Dot to enable embedded finance.

These extra-industry partners are often a black box to the companies they support. This introduces dangerous “unknown unknown”6 risks. When those providers can implode under pressure — as the Synapse bankruptcy showed — it’s not just the company that suffers — it’s their customers.

So, the question isn’t whether embedded finance works — it does.. The question is whether companies will learn the right lessons from the past. Because if you lean on something long enough, it eventually becomes a crutch you can’t let go.

Some more questions to consider:

Will Big Tech firms limit their financial exposure or go deeper? The rewards for financialization are great, particularly when priced at tech multiples (15-20x) rather than bank multiples (8-10x). With a market measured in the hundreds of billions, there’s a scramble to get a slice of the pie. Embedded finance cash flows can add jet fuel to R&D and expansion, or be used to streamline internal issues. Alternatively, they could be used to finance buy-backs, manipulate earnings, and chase quick revenue gains.

Will regulators force embedded lenders to act like banks? The financial data access (FIDA) framework and the third European Payment Services Directive, have brought increased scrutiny to embedded finance in the EU. The OCC and CFPB (for now) are examining the implications of embedded finance in the U.S. which could force companies to partner rather than take on the risks of building in-house. Regulation could mean maintaining capital requirements, additional consumer disclosures, or enhanced bank partnership models.

Disclaimer: I am an employee of Global Payments. The posts (or views) on this site are my own and do not reflect the positions, strategies or opinions of Global Payments Inc.

GE was founded in the “Gilded Age” and financed with the help of titans such as J.P. Morgan, Anthony Drexel, and Samuel Insull. It was the “Big Tech” company for more than 60 years — producing the literal engines that propelled the US to the forefront of world manufacturing and commerce. In the 1960s and 1970s, its hard tech and manufacturing was displaced and later eclipsed by the electronics tech industry while low-cost overseas competition finally caught up. I get into it later, but these two factors serve as sort of a catalyst for the financialization of the business.

This is the polite way of saying the women of the house, as domestic tasks often fell on the mothers, daughters, and grandmothers. Anyone who’s even had to use a scrub board and line to wash clothes understands just how much time and effort it takes to clean clothes.

Synchrony is or has been the issuer behind credit cards for Amazon, PayPal, Lowe's, and Verizon. They’re still the largest private label issuer in the country.

Source: “GE Capital: The House that Jack Built” by Dexter Van Dango. Welch’s legacy is mixed, to say the least. I was first introduced to it via Rana Foroohar “Makers and Takers” and have been attempting to justify a neutral view of his time at GE ever since.

This gets into a larger theme around unit economics for companies that have been propped up by easy access to funds from the capital market. “Watch your costs” is the most common refrain from old-school founders and business leaders, and for good reason. Controlling your costs gives you more leverage in pricing, winning deals, and riding out financial panics.

Q: Could I follow up, Mr. Secretary, on what you just said, please? In regard to Iraq weapons of mass destruction and terrorists, is there any evidence to indicate that Iraq has attempted to or is willing to supply terrorists with weapons of mass destruction? Because there are reports that there is no evidence of a direct link between Baghdad and some of these terrorist organizations.

Rumsfeld: Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns -- the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.

And so people who have the omniscience that they can say with high certainty that something has not happened or is not being tried, have capabilities that are -- what was the word you used, Pam, earlier?

Q: Free associate? (laughs)

Rumsfeld: Yeah. They can -- (chuckles) -- they can do things I can't do. (laughter)