Is It Faster Payment or Credit in Disguise?

How fintechs and banks are quietly underwriting speed

Disclaimer: I am an employee of Global Payments. The posts (or views) on this site are my own and do not reflect the positions, strategies or opinions of Global Payments Inc.

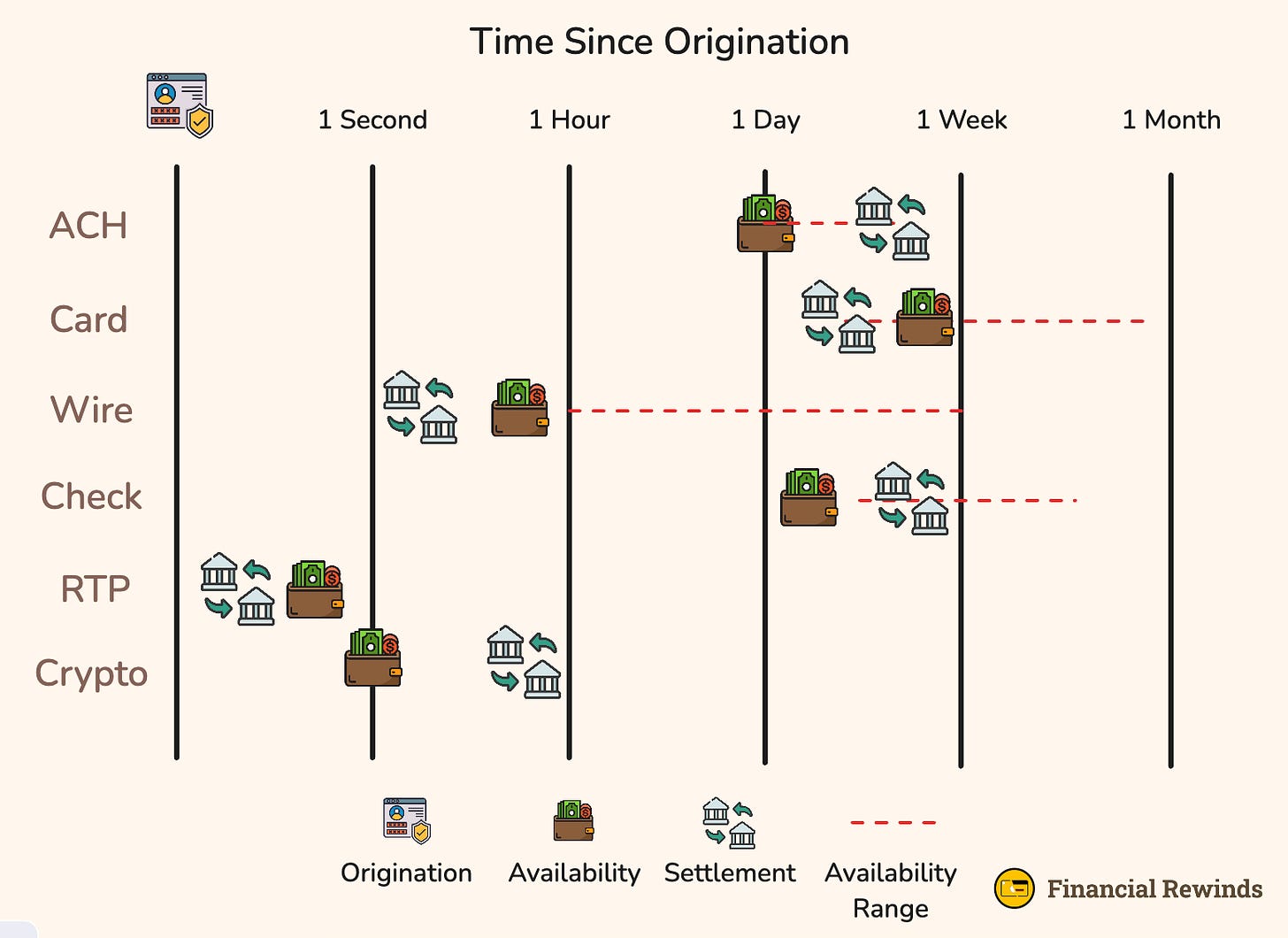

Most people think a payment is instant, but two words define whether the money is actually yours: Availability and Settlement. These terms are often conflated and confused, but failing to understand the nuance is the difference between paying the bills and losing your shirt.

In truth, managing the float between availability and settlement is an act of underwriting. Whether its called that or not, offering funds before settlement is a form of credit. Banks and fintechs front the risk based on trust in transaction timing, payer identity, and network reliability. For anyone spending the funds, they may be unknowingly taking the risk of having their funds recalled.

This post goes into how this works in theory and practice. It also explores how companies like Stripe and Melio are able to offer If you haven’t already, I recommend checking out my previous post: Who Profits from Slow Payments? It will provide much of the context for this post.

What Looks Like Speed Is Usually Credit

It’s common to have funds settled (be finalized) before they’re made available for spending. There are structural reasons — like the rail settling in near real-time, eliminating the need for advancing funds — but mostly, it’s a matter of risk management. Taking on unnecessary counterparty risk without compensation is bad business.

When money appears “early,” it’s rarely because the payment system itself has gotten faster. It’s because a financial institution is confident enough to front the money (extend credit) — and absorb the risk of being wrong. This is the engine behind the trend of “early direct deposit” offerings. Free credit is a risk more and more banks will take for consumers, but virtually none will take for businesses.

To get access to funds faster (i.e., receivables factoring, working capital lines of credit, or invoice discounting), businesses will need to pay. Sometimes, this is through interest on a loan while for others it’s a discount against a payout. The latter is used in some BNPL schemes and is analogous (though slightly different in end purpose) to merchant discount rates seen in credit card processing.

Before getting into the examples, it’s important to understand exactly what availability and settlement mean — and the nuance in how they differ.

Availability: Can I use the funds?

Availability is the nuance I left out of Who Profits from Slow Payments? For most people, availability and settlement are synonymous. If you can use your funds or see it’s been deducted from your balance, then you generally stop caring about the transaction. The only time most of us experience an issue is on the rare occasion we receive a bad check.

Businesses use a variety of methods to send and receive funds, compared to mostly ACH deposits for consumers. If the business is cash strapped, having access to the funds can mean the difference between staying open and closing shop. This is why a large number of businesses rely on short-term credit — like credit cards or working capital lines of credit — to smooth the time between invoicing and funds availability.

Settlement: Are the funds mine?

Settlement is the final transfer of funds. In accounting terms, when funds are settled, the account receivable (for the payee) and the account payable (for the payer) are set to 0.1 If funds are available or transactions approved prior to settlement, then risk creeps in. These counterparty risks — insufficient funds, fraud, reversal — are why banks don’t immediately pay out credit card charges to merchants. For individuals, counterparty risks are why there are limits on mobile check deposits.

Why The Nuance Matters

No matter what you’re managing — a bank, a payment system, or a business — these distinctions and nuances aren’t just academic. They shape product design, risk exposure, and business success. The real costs of bridging float — that is making funds available prior to settlement — are in risk (mis-)management. As I wrote previously: the float acts as insurance against these risks.

Inside the float window:

Payers can reverse suspicious charges

Payees receive a guarantee that payers have sufficient funds to complete the transaction

Banks and payment companies ensure compliance with rules, policies, and regulations — complicated even on the simplest transaction

When funds are made available prior to settlement, risk is introduced. How these risks are managed varies by use case — some examples:

Deposit Banks — Early Payroll

When we receive early payroll, the bank isn’t getting paid faster by the employer. It just trusts that the ACH will land on time and extends the credit for free. On an average paycheck, this service costs the bank about $1.50 once funding costs, reversal risk, and processing are taken into account.2 Banks absorb the cost as a competitive strategy. They make up some of it by offering lower deposit rates on funds or through interchange.

Stripe Capital — Receivables Based Lending

Lending against outstanding receivables (“factoring”) is a staple of commerce. Lenders like Stripe (“factors”) will offer short term loans equal to some discounted amount of a business’s pending sales. By being plugged into the transaction flow and order history, Stripe can model projected sales more accurately than most lenders.

Stripe’s insider data stream along with lending fees and interest, provide security against risk. To further mitigate risk, the repayment of the loan taken as a fixed percentage of daily sales. This only works because Stripe controls both the flow and the risk model — underwriting with real-time, operational data.

Melio — Pay by Card & Settle by ACH

Fintechs like Melio allow businesses pay vendors with cards, while the vendor receives ACH. In essence, they’re a payments transformer — allowing companies and vendors to use their preferred payment method. In exchange for taking on the risk of faster payments, Melio charges a 2.9% fee for card payments. Their last line of defense is a clawback clause — allowing them to retrieve funds from vendors or payers in the event of disputes or fraud.3

Bridging the Float Gap Is Risky — But Worthwhile

Whether you offer early payroll, instant merchant settlement, or card-to-ACH conversion, you’re not just speeding up payments — you’re absorbing risk. However, as volumes scale, even a tiny increase in counterparty risk can wipe out margins — turning a profitable operation into a crippling liability.

The smartest fintechs know this. They build infrastructure that knows which transactions to advance, how long to float, and when to hold back. Companies like Stripe and Melio embed themselves in the transaction flow. As a result of this data, they can price float in real-time. Plugging into the core transaction flow is what separates real infrastructure from just-an-interface.

As rails accelerate and expectations rise4, the winners won’t be the ones who move money fastest. Because payments isn’t just about movement — it’s about timing, exposure, and trust. Float is the hidden force underneath it all. The ones who thrive will be the ones who know exactly how fast they can afford to go.

Norman, Ben and Shaw, Rachel and Speight, George, The History of Interbank Settlement Arrangements: Exploring Central Banks’ Role in the Payment System (June 13, 2011). Bank of England Working Paper No. 412, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1863929 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1863929

For those curious, here’s the calculation:

The average weekly paycheck is ~$1,194 (per Q1 2025 Bureau of Labor Statistics).

Interest/opportunity costs are based on overnight bank funding rate of 4.33% over two days and uses this formula:

Reversal rate costs are assumed to be 0.1% or $1.19, with processing & management costs assumed to be about $0.10.

This gives a grand total of $1.57 or 1.31% of the total paycheck.

Melio uses Fiserv to enable core services and faster payments. But looking at the numbers and time windows they list, it looks like they almost exclusively use same-day ACH. Looking at the footnotes on their website, we see them reference 02:00 to 19:00 ET, Monday-Friday availability. Thing is, Same Day ACH only clears three times throughout the day with cutoffs at 10:30, 14:45, and 16:45 ET. From the terms of service:

6.6. Faster Payments. Melio may make available to approved Payors and/or Recipients a service that enables such Payors and/or Recipients, as applicable, to request that certain eligible payments be delivered more quickly via Same-Day ACH, real time payments, push to card payments, and expedited mailing of checks (“Faster Payments”). Faster Payments may be subject to an additional fee which will be displayed to an approved Payor and/or Recipient, as applicable through the Services at the time such Payor and/or Recipient requests a Faster Payment. In connection with Faster Payments, Payors or Recipients, as applicable, remain responsible to Melio for chargebacks, clawbacks and ACH returns pursuant to Section 13

resulting in, what I’ll call “real-time receivables factoring”