A Primer on Open Banking in the U.S.

Notes from a fireside chat on Open Banking the U.S. with Peter Tapling & Geoff Scott, head of compliance at Aeropay.

Disclaimer: I am an employee of Global Payments. The posts (or views) on this site are my own and do not reflect the positions, strategies or opinions of Global Payments Inc.

“This is the year of Open Banking” has been a rallying cry for the past five years in the U.S. However, the free & easy exchange of bank data in the U.S. hit a stumbling block earlier this month. The CFPB1 announced that the definition of a key rule — Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act — was going to be revisited.

This comes just months after a standard had been established and banks began making plans to become compliant. While the future of Open Banking in the U.S. is uncertain, banks are moving forward with the new standards set in October 2024. All that is known is that the current administration is pushing for market-driven regulation in an era of rapid technological advancement, a dangerous recipe if not managed carefully.

“The administration is considering backing off on the rule in its entirety... but I will go out on a limb and say it doesn’t matter, because financial institutions are going to do open banking. It would be better... if they did it in a standardized way, but if they don’t... it’s still going to happen.”

—Peter Tapling

Regulatory Background & History

U.S. open banking efforts stem from Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act. This section has three important mandates collectively known as the Personal Financial Data Rights (PFDR) rule:

Consumers must, upon request, receive their financial data from a bank for free.(with a few restrictions)

All data sent to consumers must be in a usable electronic form.

The CFPB will establish a standard format for data

This simple mandate was set in 2011 and finally went into effect in 2024 after years of committees, lawsuits, and revisions. The turf war between the CFPB and industry groups added to the delay, but genuine concerns over privacy and technical readiness also delayed the rule. This delay had the benefit of allowing other countries to implement open banking with the final PFDR rule being inspired by the UK’s Open Banking model and account switching tools.

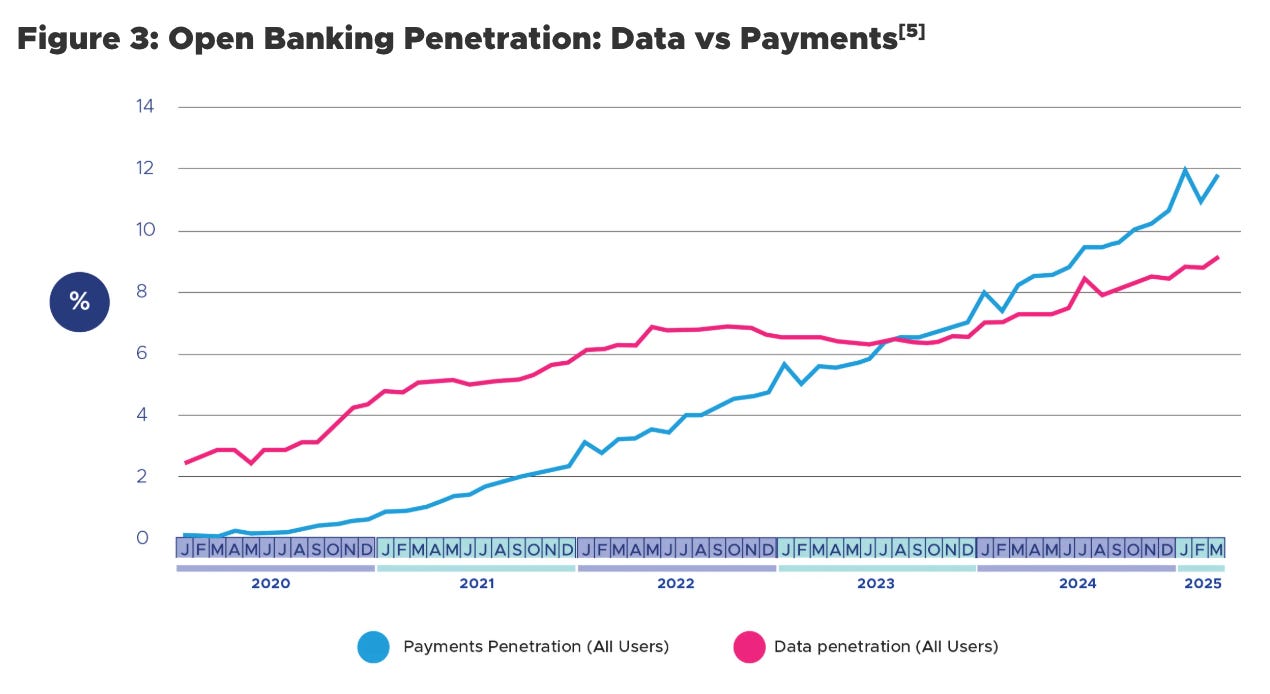

Since launching in 2018, the public-private regulatory partnership has seen 20% adoption among consumer and business bank accounts. The free, standardized flow of information has enabled neo-banks like Monzo to easily consolidate their financial life in a slick, easy to use app.2 While the UK’s model was a major inspiration, the final PFDR rule is more mechanically complex.

Rule Mechanics & Implementation

“Once the API is done, it’s a document. It doesn’t do anything.”

— Geoff Scott

The PFDR rule mandates standardized APIs for data transmission and standard-setting bodies. The original idea of porting the UK model evolved into a sprawling series of use cases and definitions that cover everything from deposit account balances to check images. To harmonize all of these definitions, a standard setter needed to be vetted.

The Financial Data Exchange (FDX) is the only verified standard setting body for PFDR. Though they’ve been selected, FDX is still developing the API standards — all of which are read-only and don’t yet support payments, check images, ACH returns, or joint accounts. This presents a challenge as the first deadline for bank adoption was set for 2026.

“While they did put in the concept of standard setting organizations, they did not put in anything related to how do you vet people who are able to use these APIs... There are no standards around them.”

—Peter Tapling

Further adding to implementation challenges are the third-party recipient concerns. This “fintech rule” for vetting is vague. There’s currently no standard process for vetting fintechs like Plaid, Acorns, Mint, or others. This has led industry participants to voice concerns over liability.

Then, there’s the elephant in the room. The current administration has appointed a CFPB lead who has called for a 90% reduction in headcount and an end to all enforcement activities. Then in May 2025, the CFPB announced it would be vacating the current PFDR rule — resetting the clock on widespread U.S. open banking.

Market Dynamics & Trends

Despite (perhaps because of) this uncertainty, the market is continuing to move forward. The three largest banks, Chase, Wells Fargo, and BofA, already support API-driven access to a limited scope of account data. This makes sense given the 2026 deadline they faced until two weeks ago, but it’s also a security move.

Have you ever wondered why the online login process for your bank seems to change every few weeks? It might be the button has moved or it now asks you to type your username, click enter, and then type your password. All of this is to prevent screen-scraping fintechs like Plaid, Acorns, Mint, and others from being able to access your account information.3

Screen-scraping poses a massive security risk for banks, because you’ve willingly shared your actual login credentials with a third-party. It also adds an intermediary between you and the bank. Intermediation from the Plaids and Yodlees has been a major threat to banks, and open banking via APIs are seen as a way to fight back.

In response to these moves from banks, middleware providers (e.g. Plaid, Yodlee, Flinks) are pivoting to trust managers and data brokerage services. It remains to be seen whether this long-term pivot will work out given bank competition and regulatory uncertainty.

Risks & Open Questions

There are many questions and risk opinions — +550 pages worth — associated with the PFDR rule. I’ve grouped the concerns discussed in the fireside chat into three buckets: Liability, Third-Party, and Commercial Incentives.

Liability: Banks are in the business of risk management. Easy access to their customer’s data is a major risk — particularly when it’s unclear who owns the liability. If data is misused after being accessed via API, who is responsible—bank, intermediary, or data recipient? Plaid was featured in a $58 million settlement for misleading customers. But for open APIs there is no firm answer right now, which should be a big concern for consumers — this may end up like filing an insurance claim and being put in an endless runaround.

Third-Party: I touched on this earlier, but the vetting of open banking third-parties/fintechs also needs to be standardized. Common standards like PSD2, PCI DSS, or CCPA provide a degree of confidence for banks working with fintechs. The U.S. could again turn to the UK and borrow their accreditation and insurance model for third-parties. “This is an area where, the CFPB and the rule passed up that responsibility,” Scott said. “It’s up to the industry to come together with some kind of standard code.” The balance between tough vetting and free-markets is a difficult one to strike, and it remains to be seen what comes next in the U.S.

Commercial Incentives: How do banks and FIs justify the PFDR rule compliance costs if they can’t monetize access? This framing comes from the banking industry. A market-neutral framing might be: what products/services do banks introduce to keep customers in their ecosystem? Regardless of the framing, the concern is valid. Regulatory compliance costs time and money which can place undue strain on smaller FIs who don’t have deep pockets.

What’s important to note, is that these questions assume open banking is the way forward. They seek to give more clarity and better define the landscape going forward.4

Why Open Banking Rules Matter

“Good rules and standards benefit all participants... Visa and Mastercard — whether you love them or hate them — the beauty is, you tap your card and it always works.”

—Peter Tapling

The rules define the playing field for banks, fintechs, businesses, and you and me. Clear, well-defined rules allow for better planning and decision making, and clearly highlights areas for innovation. The biggest area for innovation in the U.S. is in payment flows.

Open banking is viewed as a key piece of the real-time payments tech tree. Adoption lags without end-to-end automation. APIs enable smooth pay-by-bank implementations in online checkout, supply chain management, and (the newest buzzword) agentic AI.

Good rules and standards benefit all participants. History has shown that in U.S. finance, these tend to be top-down — often in response to a crisis. Perhaps the US will succeed this time in bottom-up, market-led adoption. What is known is that the future of open banking in the U.S. is coming, but the door is once again open to define it.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, one of the key banking, payment, and financial regulators in the U.S. The CFPB was established by the Dodd-Frank Act in 2011 to write and enforce rules related to consumer finance, principally mortgages, credit cards, student loans, and predatory lending.

However, the growth has primarily been in payments (i.e. “Pay By Bank”) vs. account switching and data management. Payment of taxes, utilities, and recurring bills like mortgages are some of the largest use cases for the UK system. Much of this is to do with bank parity — there’s little need to switch when there’s only a handful of functionally identical banks — and the “stickiness” of consumer banking relationships.

Some fintechs have relationships with the banks that eliminates the need for screen-scraping, but it’s still widely prevalent.

Screen scraping is actually how I got into fintech. I built screen scrapers for mainframe screens at SunTrust/Truist using Visual Basic because actually getting the data from any other source could take days or even weeks.

A good extension would be to examine what the market looks like depending on the answers to these open questions.

For example, if API data risk sits with the bank, you can expect a rigorous vetting process along with fees for that vetting to be passed to the third parties (importantly not the consumer).

Another example: what if there’s a small bank exemption for PFDR rules like there is for Durbin interchange? How does the Banking as a Service (BaaS) model change in this environment?

I thought the CFPB open banking framework was rejected by the current administration. Any idea if they're coming up with new regulations?

Great article. I've never understood the open banking thing because of how quickly it can get so complex and expensive. In Australia the banks spent a fortune on open banking and constantly have to meet new regulatory demands - yet there are very low (if any) benefits accruing to customers.