Payments. Explained for Everyone.

Payments 101 and ways to think about money movement in 800 words.

This one is for my colleague Shenika, because no one really goes to school for payments.

It’s a critical industry that enables the global economy, but most of us learn on the job. I was lucky enough to have a mentor to explain the basics. My mentor, Neal, taught me how payments move — the foundation for a successful career. Why? Because once you understand it, you’ll realize who profits from slow payments, why Substack won’t build tips, how airlines are just loyalty program operators.

Inspired by Matt Brown’s excellent “X in 1,000 Words” series, this is what I would say to my friends and family ask “what do you do?” or a new-hire who asks “how do we make money?”

The Basics — 2, 3, and 5 Party Models

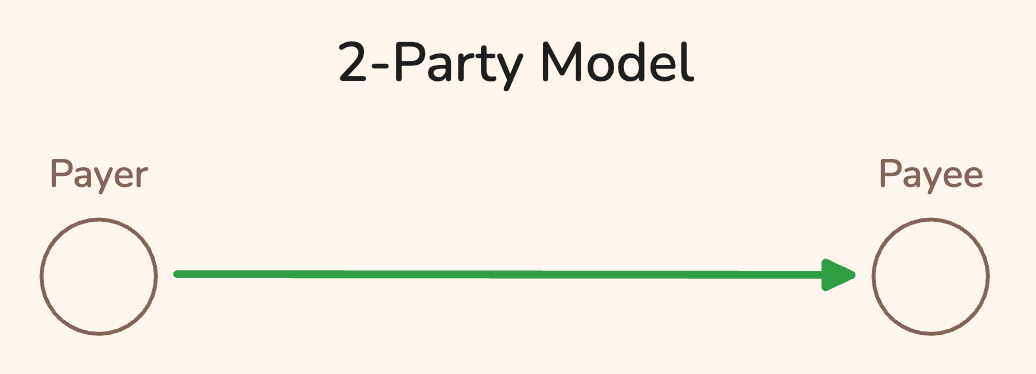

A payment is the transfer of money. It can be gold, paper notes, or electronic funds. All that’s needed for a payment is trust in the medium of exchange and trust between the parties involved. The most simple type of payment is between two parties: a payer (the one giving the money) and a payee (the one receiving the money).

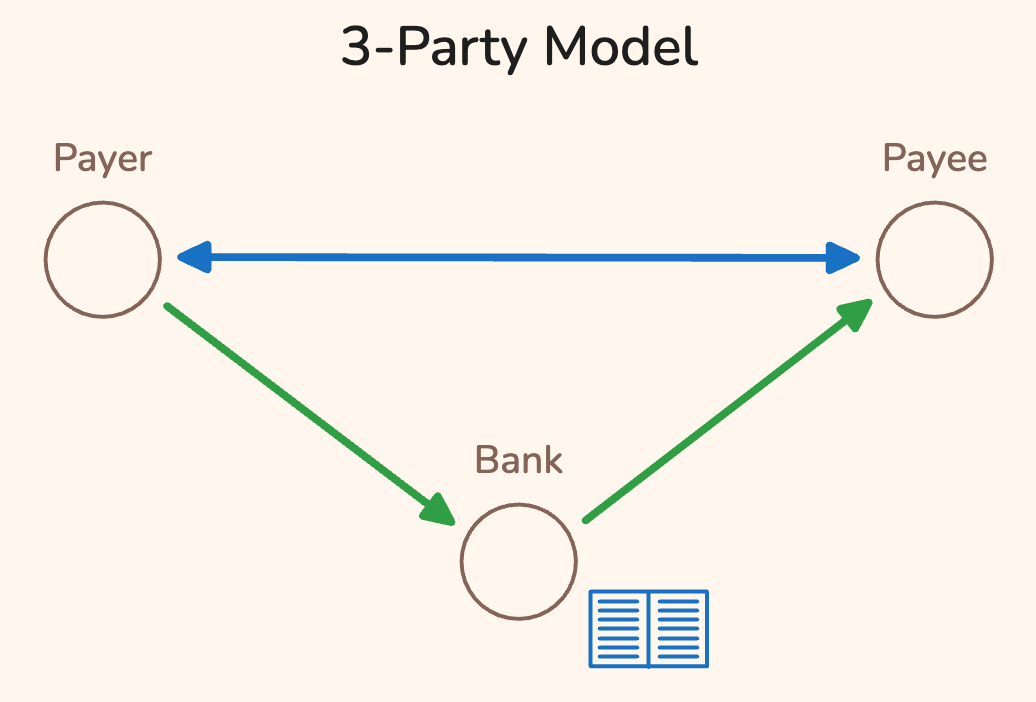

Carrying around and storing currency can be a challenge. To make the process easier, we can add a third party: a ledger keeper (aka a bank). This ledger keeper tracks balances for both the payer and the payee and moves balances between people. (For simplicity, I’m going to label these “banks” but know that not every ledger keeper is a bank.) Conceptually, this how is American Express, Paypal, Apple Cash, and Bitcoin work.

The three party model relies on the payer and payee having the same bank and shared ledger. If the payer and the payee don’t share the same bank, then we have the four-party model: payer, payer bank, payee, and payee bank.1

Those of you in the industry who are about to click away at the upcoming heresy, please, please see the footnote first.

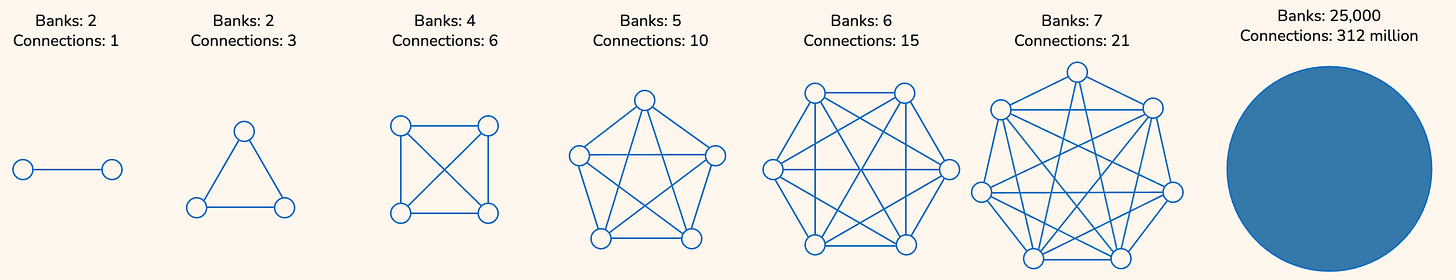

This works fine if there are only a few banks. But it falls apart when the network gets larger, which is why it doesn’t really exist outside of small banking systems or between central banks. If all of the estimated 25,000 banks in the world were connected to one another, it would require more than 312 million unique connections.2

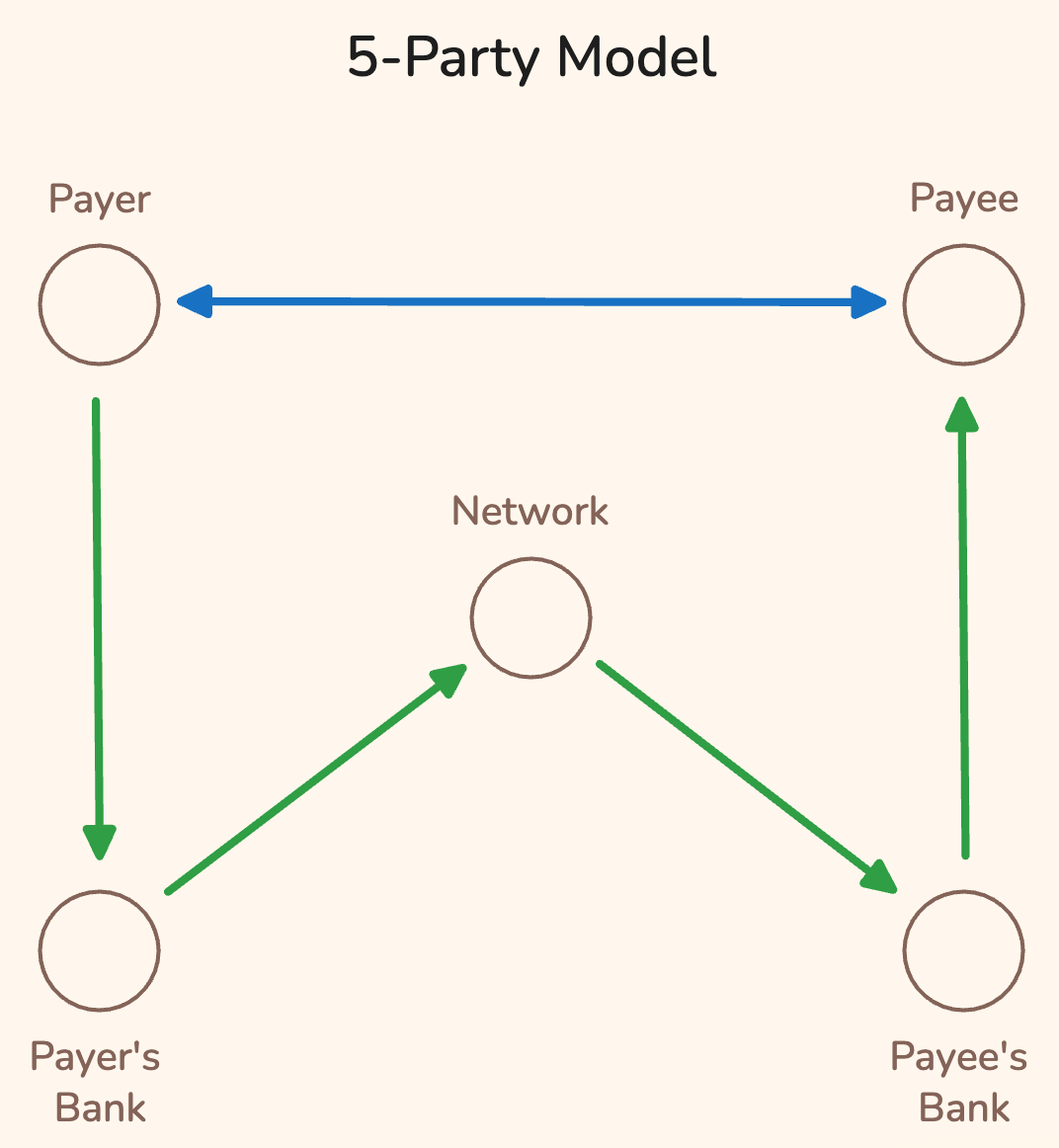

This scenario is intentionally impractical and improbable, but does raise an important question: how do you effectively connect the banks? To solve this, banks regularly turn to a fifth party: networks.3

Network operators reduce the complexity of connecting two banks. The five-party model is the basis for most modern payment systems like credit and debit cards, ACH, wire, and real-time systems.

In cards, people will often call this the “four-party model” as the network is folded into the line connecting the payer and payee banks. I’ve chosen to separate the network here because it’s a distinct party making its own decisions.

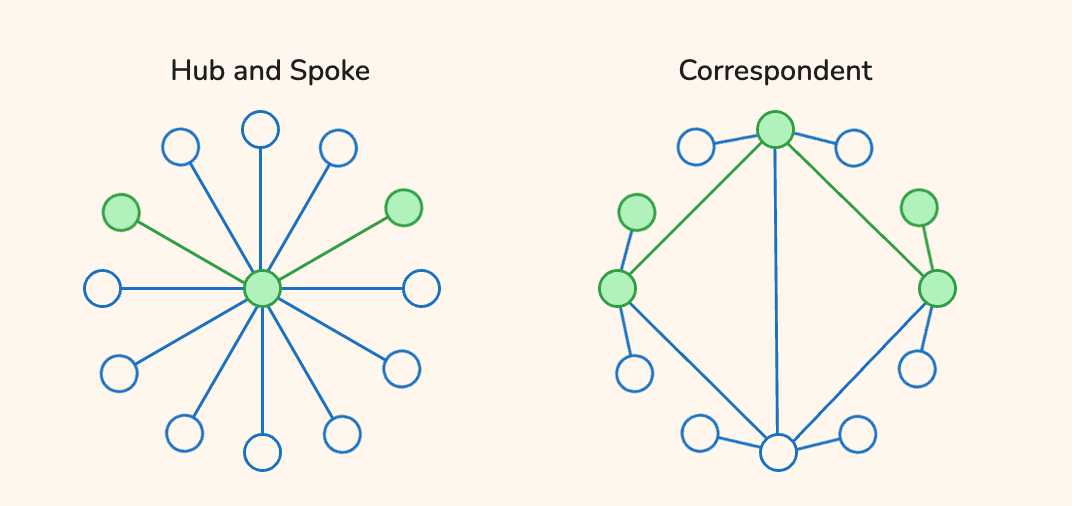

Some networks, like Visa, Mastercard, or Fedwire, are a hub and spoke model: maintaining direct connections with all financial institutions in the network. Others, like those used in international transfers, use correspondent networks and rely on multiple connections to connect two banks.

For simplicity, all the various network types are shown as a single circle, but it helps to know that there may be more going on behind the scenes depending on the payment.

Now that you have the basics of 2, 3, and 5 party models, let’s do something with it.

Using these models to understand the payments FAQs

To sure up our understanding, let’s answer two different questions:

Why doesn’t everyone accept American Express (Amex)?

Why does it take days to send money internationally?

Why doesn’t everyone accept American Express (Amex)?

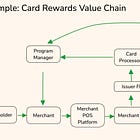

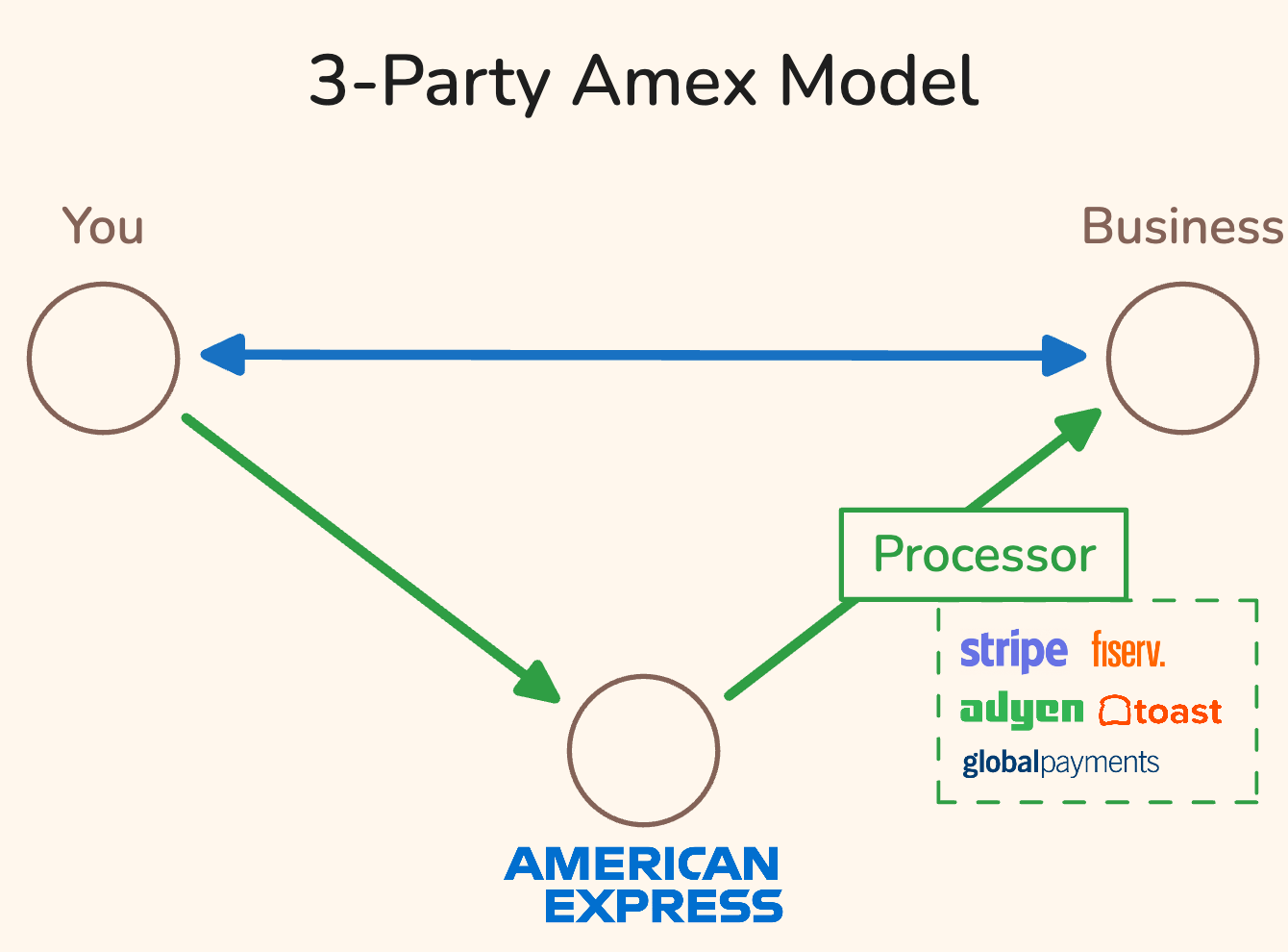

Let’s start with the three-party model to understand why stores and restaurants might refuse to accept Amex. Amex is a bank, and when you spend money on that card, you’re borrowing from Amex.4 If a business wants to accept an Amex card, then they need to have a merchant bank account with Amex. This makes Amex a three party model: You, Amex, the business.

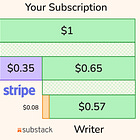

This extra bank account can be expensive and complicated to manage, so most business have their payment processor manage the account. This adds cost to the transaction on top of the fees charged to the business for accepting the card (e.g. “interchange”). For some businesses, these costs are too high, especially given that almost every Amex cardholder is likely to also have a Visa or Mastercard in their wallet. This is why many will opt out of accepting Amex — especially outside the US.

Why does it take days to send money internationally?

And why is it so expensive?

International transfers are based on a five-party, correspondent model. Unless you’re sending funds from one mega bank to another, your money is going through a web of nostros (literally “on us”) accounts in addition to changing currencies.5 Each of these adds cost, with the former adding significant amounts of time.

At each step in the transfer, banks have to perform some level of fraud and risk checks. This adds time and cost to the transaction. Most banks run wires only a few times a day, so depending on the number of jumps your money has to take and when you send it, it could be anywhere from two days to two weeks before it arrives.

This post only just scratches the surface of how payments work. It’s all things that I wish I’d understood much earlier, because it explains why companies make the decisions they do. If you have a nagging question, feel free to send a reply to this email or drop it in the comments — I read and reply to all of them.

Typical industry blogs and explainers will say that this is the end of the story. I disagree, for reasons which I explain in ~100 words. There’s another footnote with an industry focused rebuttal.

Some back of the napkin math says we’d need about 460 billion miles of fiber optic cable. That’s ~1,500 miles for the average connection. For context, that about 180 times more than all the fiber optic cable on earth today.

Before I take flak from the payments community: Yes, I know that it’s usually referred to as the “four party model.”

Historically, Visa, Mastercard, and the other network operators have acted as switches. When Visa and Mastercard were owned as bank consortiums, profits from the networks were paid out as dividends to banks shareholders. This is a perfectly acceptable way to view things given that scenario, but Visa and Mastercard have been independent companies for 20 years now. They are separate entities with roles bigger than just serving as a switchboard. Mastercard now makes more money from value-added services than it does from basic network operations. Therefore, I feel justified in claiming that networks ought to be called out as separate entities and that the four-party model needs to be retired in favor of the five party model that more readily accommodates payment methods like RTP or stablecoins.

Again, gross oversimplification. American Express is a bank. They offer banking services such as deposits and lending under a national bank charter (OCC Charter # 25151, FDIC Cert # 27471). They issue credit cards like other banks. What makes Amex and, say, Bank of America different is that Amex operates its own card network rather than a third-party like Visa or Mastercard. This network is “closed-loop” meaning that Amex cards only work at merchants registered with Amex.

For those of you wondering, this is where the “nostros fee” line item on your bank statement comes from.

Really enjoyed this framing! I recently shred a post talking about stablecoin adoption by banks and how it could impact payment networks. Would love to hear your thoughts!

https://open.substack.com/pub/theuncredentialed/p/wtf-are-stablecoins?r=26ya72&utm_medium=ios&shareImageVariant=overlay