The Rise, Fall, And Legacy of Firethorn

They built the future of mobile payments before the world was ready — and watched it slip away.

In the late 2000s, the future of payments was uncertain. A new technology, the smartphone, was fundamentally changing possibilities in commerce and payments. Mobile carriers had long monopolized mobile payments, but Apple had just put computers in everyone’s pocket. And the payments industry was scrambling just to have a hand in shaping their future.

SWAGG was a bold attempt to redefine mobile commerce — a last-ditch effort to keep Firethorn’s dream of a universal digital wallet alive. It was born out of necessity and wildly innovative. Its solutions and its team laid the foundation for Apple Pay and Google Pay, but it was a product ahead of its time. And in the world of technology, being early is the same as being wrong.

Firethorn’s arc — from explosive growth to quiet collapse — are lessons in what happens when innovation collides with real-world frictions. Its legacy continues to shape payments every time you tap your phone to pay.

This is the story of how Firethorn sought to redefine what payments could be — told by the people who lived it.

An incredible debt is owed to Aidoo “AO” Osei, Frank Young, Robert Dessert, and the many other Firethorn and Qualcomm employees who contributed their experiences to this story.

I. The World Before Apps

The State of Mobile Banking in the 2000s

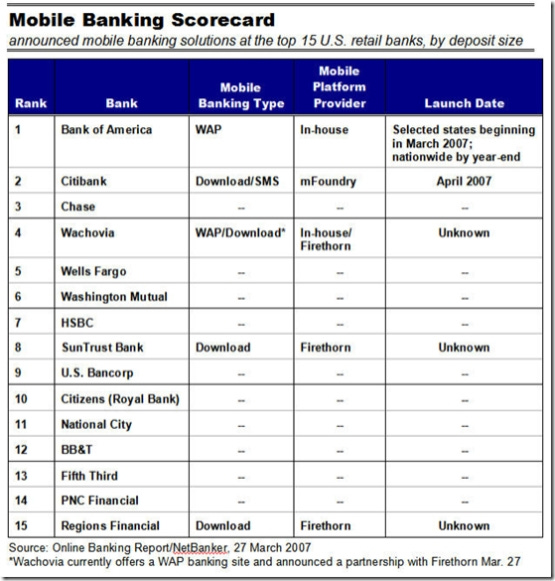

Before being app and hardware-led, mobile banking and payments were dominated by mobile carriers. The largest carriers at the time — Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and MetroPCS — kept a tight leash on the experiences available to their mobile customers. If a bank wanted to enable mobile banking, they had to go through the carriers. Carriers, however, didn’t integrate directly with the banks. Instead, they used a short list of approved developers including ClairMail, mFoundry, and Firethorn. However, only Firethorn held preferred status with carriers and came pre-loaded on the phones.

Firethorn

Founded around 2001, Firethorn connected financial institutions and carriers through a single, secure platform.1 Firethorn did this through developing back-end infrastructure and links to banks and credit card companies and enabling those connections via a mobile app.2 This stood in contrast to ClairMail which was SMS based and mFoundry which built separate apps for each bank.

The Firethorn solution enabled full-service banking capabilities for consumers — bank accounts, bill pay, and balances — into a secure mobile app. The app serves as a digital replacement for the physical wallet, designed in alignment with wireless carrier expectations for a single, consistent user experience, controlled by one PIN.

As one of the only carrier preferred third-party bank apps, Firethorn was in a unique position. “If you were a bank and wanted to get on [the carrier’s] phones, you went through Firethorn,” said Frank T. Young, head of business development at the time. This power is why users could add multiple financial institutions (e.g. Wachovia, SunTrust, and BancorpSouth) into the same app instance rather than individual bank apps.3

In a time when mobile internet was charged by the megabyte, Firethorn brought mobile banking to millions. Their platform was free for customers to access, but using the application came with charges from the carriers and banks. Firethorn then received a cut of these fees from the carriers and banks.

At its peak, Firethorn earned $6 per user per month. With 126 million mobile subscribers between Verizon and AT&T, the addressable market seemed enormous. It was enough to attract Qualcomm — the company that enabled most phones with their wireless chips.4 Firethorn wasn’t just another mobile banking vendor. It was positioned to be the gateway to digital wallets — and Qualcomm saw that before almost anyone else.

Marrying Hardware & Software

Qualcomm had been an early investor in Firethorn — earning the internal nickname “the Bank.” Their relationship with “the Bank” got Firethorn in the door with carriers, because Qualcomm’s radio technology powered much of the mobile industry (both then and now). Then, in a whirlwind weekend, the Firethorn leadership team inked a deal with their financier.

Qualcomm acquired Firethorn in September 2007 for $210 million in cash. The stated rationale for the deal came down to Firethorn’s extensive banking network and carrier relationships. Qualcomm shares rose 5% following the announcement of the deal:

The addition of Firethorn's expertise in the financial industry and key relationships with wireless operators, financial institutions and payment processors supports Qualcomm's broader strategy to enable end-to-end wireless services that enhance the mobile experience and to deliver compelling applications that drive increased consumer adoption of new mobile data services

The deal also married Firethorn’s software and network with Qualcomm’s chip and radio hardware. This combination overcame a key concern for banks entering mobile payments: security.

As one industry observer at the time put it:

The most secure thing is to do [mobile banking software] through hardware. If, like Qualcomm, you’re the chipmaker working with people on the back end, you can put something right into the hardware that can’t be copied. That, and wanting to get involved in the infrastructure, is probably why Qualcomm is buying Firethorn.

The market opportunity was in the billions and the potential for growth was enormous. Firethorn’s model seemed solid – until a seismic shift in mobile tech changed the rules overnight. The team had no idea that within two years the user fees paid would fall 98% — from $6 to just 10 cents.

II. Shock to the System

The inflection point for Firethorn — and the whole world, really — was Apple’s release of the first iPhone in July 2007. Though it was locked to AT&T and initially mocked as less functional than a BlackBerry, the iPhone ultimately put a user-friendly computer in everyone’s pocket.

But what made the iPhone special was its use of third-party vs. carrier enabled apps. The same month Qualcomm announced its $210 million acquisition, Bank of America released their first iPhone app, bypassing carrier portals entirely. Thus, the first crack appeared in Firethorn’s foundation.5

Disruption: The App Store Changes Everything

Made available in July 2008, the App Store enabled third-party developers to build apps that could be directly installed on a user’s iPhone. Steve Jobs, learning his lesson from making Mac OS a walled garden, opened the App Store developer tools (SDK) to all. By opening the SDK to all developers, Apple handed power to app creators — and took it away from carriers like AT&T and companies like Firethorn.6

As one Kleiner Perkins partner explained at the time, “A lot of the best entrepreneurs haven’t wanted to start anything because the carriers had to bless you.” Access to SDKs enabled developers of all stripes to build and ship products (with Apple’s blessing) for users to download. This one change upended Firethorn’s entire business model.

Within weeks of the App Store launch, major banks — including Firethorn’s partners — were releasing their own mobile banking apps. Firethorn responded by launching an app of its own: Mobile Banking on AT&T (screenshot below, link to 2009 demo), but by then, the ground beneath them had already started to crumble.

The iPhone and App Store triggered what Young called an “existential response” inside Firethorn. No longer essential as a bank-on-phone gateway, Firethorn had to reinvent its value proposition or be disintermediated to oblivion. The challenge was staying focused on the right innovations rather than riding the hype wave or building pet projects. What began as a defensive move soon turned into something much more ambitious.

A year after the acquisition and 4 months after the App Store was released, Firethorn announced a wave of new features — loyalty, rewards, personalized offers, geofencing ads — all in a bid to move from banking utility to mobile commerce engine.

On the surface, Firethorn was trying to smoothly transition from being just a bank access provider to the enablement partner for mobile commerce. But the 2008 announcement buried the lede a few paragraphs in: Firethorn intended to be the ones to introduce true mobile payments — something that at the time only existed in futurist forums and magazine columns.

The product and business development teams behind the scenes were frenetic. “We had this idea of being a ‘universal wallet’ and set out to build it long before digital wallets were a thing,” Aidoo “AO” Osei, a senior product manager at the time, recalled. “We explored a bunch of ideas — near-field communication partnerships with First Data, digitizing state lottery tickets — before landing on digital wallets and gift cards.”

III. The Dream of a Universal Wallet

Creating the first mobile wallet

What came next was as ambitious as anything in Silicon Valley at the time: build a digital wallet for the future — years before Apple Pay or Google Pay existed. To do it, the Firethorn team would need to overcome a series of challenges.

The first challenge was compliance — where most fintech ideas die. The team worked to ensure that data was secure and met the PCI DSS standards set by Visa and Mastercard.7 The next came the challenge of how to make card payments from a mobile device.

Near-field communication (NFC) technology — the tap-to-pay tech we use today — existed, and the team even piloted an NFC solution with First Data. But in 2008–09, neither consumers nor merchants had the necessary hardware, and security concerns loomed large.

Everyone [in the industry] understood the phone could do something when it came to payments. No one was quite sure what or exactly how. — Robert Dessert, Sr. Director Product Strategy

To solve this, the team at Firethorn built on their original idea8 of a financial “super app” — turbo charging it with account management, additional payment methods, offer presentment, receipt management, and more. It was from this foundation that Firethorn would try to dominate mobile payments. Along the way, the team had a breakthrough — the kind that still impacts the way we pay to this day.

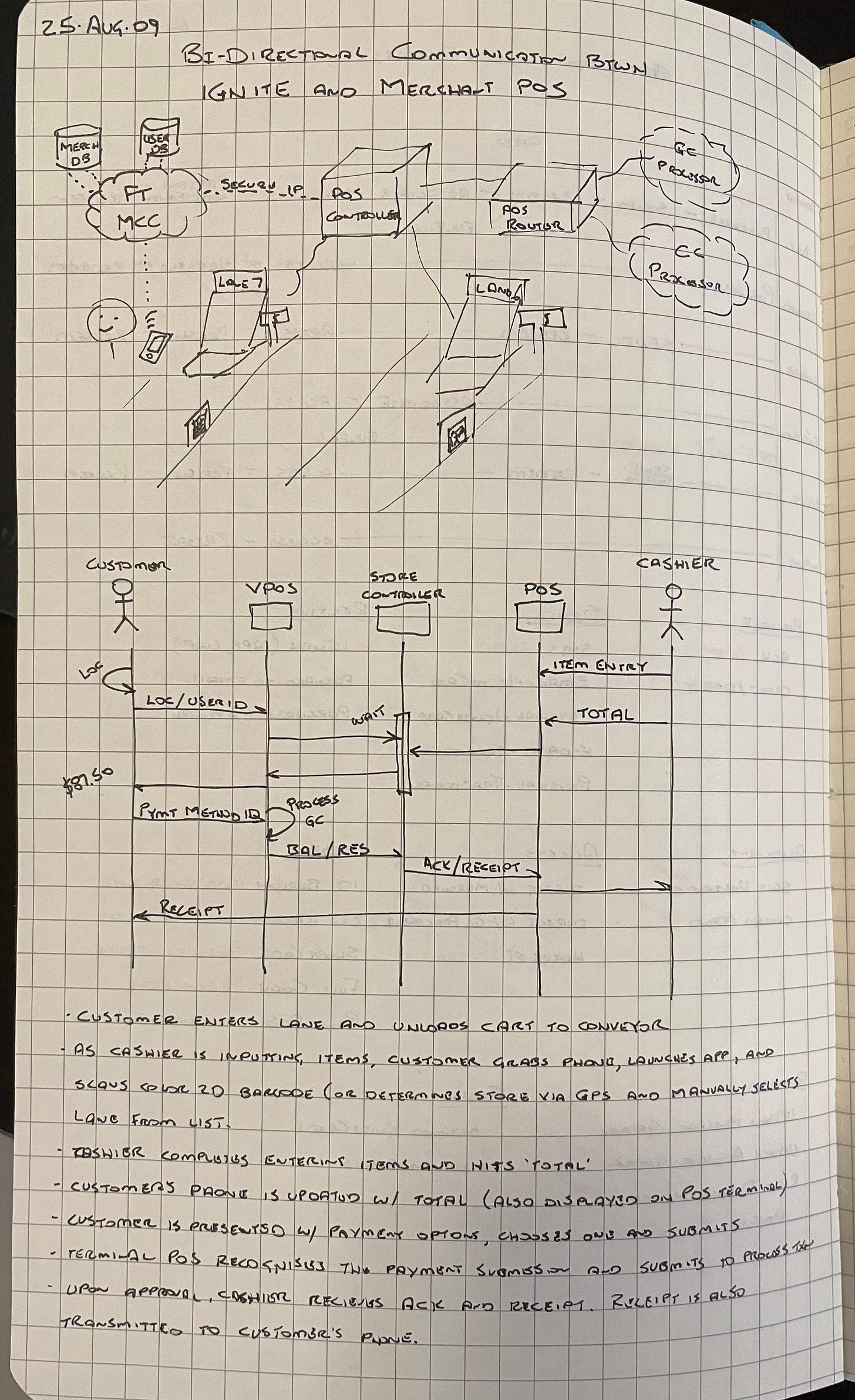

A Late Night Sketch of Tokenized Payments

One night, I sat up and opened my notebook. I jotted down an idea for a mobile payment system and bookmarked the page.

— Robert Dessert, Sr. Director Product Strategy

The bookmarked in Dessert’s notebook is the first sketch of a foundational patent still used by Apple and Samsung Pay to this day. Firethorn had already worked through storing credit card information on their database and using that information to make credit card payments. The risk and compliance challenges, however, made this system untenable for the company.

Then, in a eureka moment, the team worked out a solution. Instead of transmitting stored card numbers — a compliance nightmare — Dessert and the team figured out a workaround: a single-use card number valid for just five seconds. It was the first real-world prototype of what would later become Google and Apple Pay. Here’s how it worked:

When a customer would present their phone to make a payment the merchant would initiate a request for payment information to Firethorn using the customer ID (CID) along with the Merchant (MID) and Terminal ID (TID).

Firethorn would then pass the CID, MID and TID to the customer’s bank.

The bank would validate the information, and generate a one-time use card number with a 5 second expiration — just long enough to ensure the transaction would process in the card network.

The temporary card number would then be transmitted directly to the merchant’s payment processor from the customer bank.

In the parlance of modern payment processing, the team at Firethorn created the first tokenized virtual card system.

One teammate, Scott Monahan, was pivotal in turning Dessert’s notebook sketch into a working product. Monahan, the lead engineer, famously solved problems others deemed “impossible” – at one point even hacking a vending machine’s credit card reader just to prove a concept. The team jokes, “if it’s impossible, give it to Scott.” In short, Monahan got mobile payments working before anyone else could.

The breakthrough in tokenization solved the security problem. But one challenge remained: how to get a one-time card number from the phone to the merchant POS in five seconds — without any new hardware. The solution? Develop a virtual card swipe.

Quick Response Payments

Robert Dessert explained the problem:

Droid [now Android] technology was open, but lacked scale at the time. Apple’s NFC feature was turned off by default. because it quickly drained the battery. It was cumbersome to turn on and [due to the battery issues] we couldn’t get people to leave NFC on all the time. We then turned to Bluetooth, but the channel couldn’t support payments — that wouldn’t come until BLE [the next generation of Bluetooth].

We tried to barcode, but we were never able to get the resolution right on the phone screen to enable the payment.

Without a method of initiating the payment from the phone, the idea was dead in the water. Instead of waiting for NFC to scale, the team engineered a way to use quick response (QR) codes as a keyboard emulator, embedding transaction details directly into the code.9 This allowed for easier integration with existing merchant hardware. As Frank Young explained it:

A QR code is just a keyboard. You can format the basic payment information in a code, scan it, and using our system it would be as if you swiped the card. The idea was that the merchant would scan it and the payment information would then be sent to the merchant’s bank the same way a normal card payment was processed.10

With the core process and methods identified, the team prepared to launch headlong into uncharted waters. The team would split the technology across two products: Ignite and Spark. Ignite would serve as the mobile wallet for bank cards, while Spark would host the gift cards and loyalty features.11

A Spark in Search of Kindling

As mobile wallets become popular, a rising question is: ‘‘Will mobile wallets replace traditional leather wallets?” Or, ‘‘How will mobile wallets be positioned in the market?”12

A payments network is a two-sided marketplace — you need both payers and merchants. As Firethorn, they’d proven their ability to get on phones and gain user adoption. But a gift card app with no redemption options was dead on arrival. To make the universal gift card wallet work, they needed merchants on their platform.

Otherwise, there’d be no value for users and the team would fall headlong into the “Field of Dreams fallacy” — building a product and expecting users to flock to it. To solve this, the team started pitching the largest merchants in the country.

“We needed to get a blue chip, marquee client with near-everyday use to really make it work,” recalled Osei. The team approached grocers like Kroger and Publix, but couldn’t make the transaction economics work with the tight margins. They then approached two of the largest retailers — WalMart and Target — but found price and employee training as limiting factors.

Young stated the problem simply, “there’s no small change to POS.” Physical merchant adoption was the big challenge, because new POS technology is expensive, employees need lots of training on the POS systems, and staff turnover is incredibly high — between 70% and 120%13. The solution needed to be “dumb simple” and integrate with what already existed at the point of sale. The latter is why focus shifted away from NFC and Bluetooth payments to barcode and QR-based systems.

“Early on, we pitched the QR code idea to Starbucks,” Osei recalled. “We were going to enable Starbucks gift card payments directly from a mobile phone.” There was one problem with this plan: Starbucks didn’t want to compete for real estate next to other merchants. The Seattle coffee giant wanted to own the customer experience and built the app in-house, partnering with mFoundry to launch the first Starbucks Mobile App in 2009.14

IV. SWAGG: Big Ideas, Big Expectations

While the engineering team was solving deep technical challenges, “the Bank” was losing patience and millions — including a $114 million goodwill impairment in 201115. Qualcomm leadership decided the product needed something else: a bold new face. And that meant more than a new app — it meant a new identity entirely.

In 2011, the Firethorn brand was retired and replaced by Outlier along with new leadership including Rocco Fabiano, President, and Steve Statler, head of strategy. To complement the change in name and leadership, the brand also received a refresh. They brought in Marc de Grandpré — a Red Bull marketing exec — and marketer Mel Clements to reimagine the concept. Over the course of one weekend, the entire office was transformed to something new, something bold.

The Reset: Deal With It

Over the weekend, the marketing duo brought in an Atlanta graffiti artist to cover “every inch of the office” with the new brand. SWAGG and its tagline “DEAL WITH IT.” — aside from being emblematic of 2010 culture — represented the edginess of the period. It was intended to be a “revolution to enhance the way consumers transact.”

SWAGG was Firethorn’s reinvention as a consumer-facing mobile wallet — focused on digital gift cards, loyalty rewards, and personalized offers. Qualcomm introduced the brand at the 2010 Consumer Electronics Show with a star studded VIP party and concert.

On January 7th, 2010 at the Hard Rock Hotel And Casino in Las Vegas, SWAGG was announced to the world. “The kickoff in Vegas was wild,” recalled Young. “We had Kid Rock as the headliner. His rider contract included provisions for gambling chips and two stripper poles.” Dessert added, “Kid Rock only had one clause in his contract for the performance — don’t sing ‘Sugar.’ So at the end of his set, the band starts playing the song and he just holds out the mic. The crowd sang the entire song.”

This bold, flashy brand image was a hit with younger audiences and had the brand featured at social events around the country. However, it alienated more conservative merchants like WalMart — dealing the first major blow to the nascent project’s long-term prospects. Undeterred by the loss, the team pressed on leveraging their brand and “the Bank’s” deep pocketbook.

A Flurry of Ideas

The original business model for SWAGG was to let consumers transfer funds between gift cards for different retailers and merchants. This would take place in one, easy to use mobile “super app”. Then more ideas were piled on, including rewards, in-store offers, and customized pricing, but this was a sign of things to come.

SWAGG had the brand. It had the tech. But it had a major problem under the surface: too many ideas. To get a sense of the scope, take a look at this excerpt from the “Just Deal With It.” trademark application:

The DEAL WITH IT. trademark is filed in the Computer & Software Products & Electrical & Scientific Products category with the following description:

Computer e-commerce and mobile commerce software to allow users to perform electronic business transactions via a global computer network;computer software and downloadable computer software for use with mobile phones and mobile digital devices for providing banking services, financial services, credit card and debit card services, gift card and rebate card services, loyalty account management, redemption and tracking services, maps and direction services, and location based shopping information and recommendation services using global positioning services (GPS) technology and other locating-sensing technology

That’s eight different solution sets spanning at minimum three domains: financial services, retail solutions, and geo-location services. The SWAGG program earned considerable hype, because they weren’t just selling vaporware — they had really developed technology.

The “super app” concept struggled under the weight of corporate pressures, technological limitations, and the challenges of building a two-sided marketplace. However, SWAGG had to justify, or at least recoup, the $210 million investment Qualcomm made in Firethorn. So the team pressed forward trying to weave them all into a cohesive product.

They continued pitching the core solution — mobile gift cards — to gas stations, fashion retailers, department stores, and restaurants. However, gift card balances aren’t revenue — they’re liabilities. And accounting for them gets messy fast, especially across 50 state-level escheatment laws. One exec put it bluntly: “It would take an Act of John to get the liability off Papa John’s books.”16

A Closed Open-Loop

The SWAGG team realized that they would need to develop another innovation to make the universal wallet dream a reality. They would need to make a payment card that could be locked into a single retailer, but give cardholders the ability to change which retailer they wanted to use. This required solving three problems:

Managing a gift and private label card program

Removing the unused gift card balance liability from the merchant

Switching the merchant associated with the card without a transaction

To solve the first problem the team turned to i2c, one of the largest gift card issuers in the country. They used i2C’s My Card PlaceSM — also used by Western Union — to manage the gift card processing. Removing the liability required a way to get the funds into a separate account managed by Firethorn. Here, they turned to early BaaS providers Bancorp and Metabank, ultimately going with Bancorp.

The last challenge, switching the assigned merchant, required the most innovative thinking. The solution they landed on involved issuing the cards on the Discover network. These cards, managed through i2C, would be open-loop pre-paid cards meaning they could be used at any merchant that accepted Discover. To lock it into one merchant, the team at Firethorn used a restricted auth network (RAN)17.

A RAN creates a sub-network within the card ecosystem. RANs restrict the merchants where a card can be authorized for a payment. This technology is what allows national franchises to accept gift cards — it’s also a factor to why your gift card won’t work with certain airport, mall, or international locations.18

Over the course of 2010, SWAGG would land a string of major retailers including JCPenney, Live Nation, Levi’s19, and Burger King.20 Leaning into the brand, they found a niche with younger brands and aging companies looking to reinvent themselves. The platform’s hype, publicity, and genuine innovations earned the SWAGG team the title of “Most Innovative Prepaid Program” and “Best Mobile Prepaid App” in 2011.

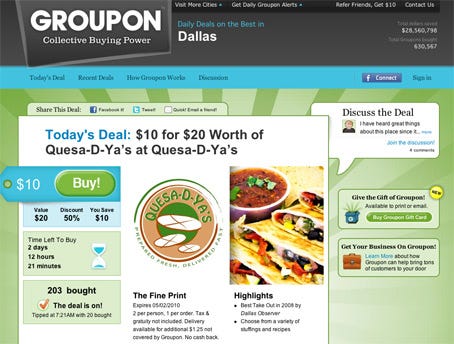

While SWAGG was lining up retailers and hosting star-studded events, a scrappy new startup was quietly rewriting the mobile commerce playbook — with fewer features, and far better timing — going from $5,000 to $1.6 million in revenues in just under 3 years.

V. The Quiet Collapse

Simple Can Be Better

What really sealed the deal [for SWAGG] was when we saw what Groupon was doing

— Aidoo “AO” Osei

Groupon, founded in 2008 by Andrew Mason, was initially a simple web platform that delivered daily deals to subscribers via email. Groupon wasn’t trying to build a platform. It just emailed you a deal and let you click to buy. Simple, familiar, and wildly effective.

These deals came from partnerships with brands and their desire to access the wallets of Groupon’s rapidly growing subscriber base. Over the following years, the company rapidly expanded its tech stack and network through acquisitions of tech platforms and various regional clones.

Groupon's core value proposition was offering consumers significant discounts on local goods and services, while providing businesses with a platform to attract new customers. This model resonated strongly during the post-2008 financial crisis, as consumers sought bargains and businesses aimed to increase foot traffic in the early e-commerce age.

Then, in 2011 the company released “Groupon Now,” a mobile app offering live location-based deals to users. Coupled with a $13 billion IPO and fresh $700 million in cash, Groupon was better positioned, better funded, and more focused than SWAGG — a project in a division in a multinational tech conglomerate — could hope to be.

The Breakdown: Too Many Cooks Throwing Spaghetti at a Wall

The explosive growth of Groupon, lack of product-brand-fit for SWAGG, and need for Qualcomm to get some ROI brought scrutiny on the SWAGG team to generate revenue — and fast. However, the innovative ideas came too quickly, and the team didn’t have the time or focus to see any of them through. Dessert put it plainly:

We kept building the newest solution each quarter — trying to chase revenue. So we continued trying to ride the hype wave and never allowed ideas to come out of the trough of despair. What we really did was take a “throw spaghetti against a wall and see what sticks” approach to development rather than staying focused on core customer needs.

The problem with this approach is that you end up with a big mess on the floor. In chasing new innovation and revenue quarter by quarter, SWAGG never gave any one idea time to survive the trough of despair — that post-hype dip where real products are forged. Instead, it created a blur of half-launched features, abandoned pilots, and missed signals. In the end, it wasn’t the next big thing that won. It was a daily email deal.

Qualcomm, by this point, was ready to move on. They had overpaid for a company whose core business moat disappeared overnight. Then, in trying to salvage something, anything, out of the business, Qualcomm ended up losing hundreds of millions trying to find a viable solution. This frustration is evident in the last public mention of Firethorn in their 2012 Annual Report (emphasis added):

The initial consumer adoption rate of SWAGG had fallen significantly short of the Company’s expectations, and as a result, the Company revised its internal forecasts to reflect lower than expected demand and reduced the Firethorn cost structure.

So the high-flying tech company went from $210 million in 2007 to $17 million in 2012 to be buried in the dustbin by the end of 2013.

VI. Mixed Legacy

Being Too Early

Among those who built SWAGG, two causes came up over and over: being too early, and chasing too many ideas. The technology was visionary — but adoption lagged, the market shifted, and even the best breakthroughs need the right timing.

It may be true that the mobile wallet is an innovative technology that can provide customers with a great convenience, but are consumers ready to embrace this new method of payment? What barriers/incentives might reduce/increase the diffusion of mobile wallets in the consumer market?

Consumers and merchants in 2011 weren’t ready to embrace mobile payments. There were early adopters who could see the long-term value, but the hard truth was that the technology wasn’t in the right place. NFC and Bluetooth were available but not at scale in stores or on mobile devices.21

The cumbersome process of scanning a code and following a different process at checkout added friction for buyers and sellers. Consumers and merchants crave simplicity. Even though the technology Firethorn and SWAGG developed was innovative, the frictions were just too much to overcome.

Firethorn wasn’t alone in this experience, either. Carrier-backed initiatives like Softcard (formerly Isis) and wallet startups like Obopay also tried — and failed — to build mobile payments before the conditions were right.

Innovation Without Focused Execution

The SWAGG brand carried a suite of solutions across several domains: payments, account management, loyalty & rewards, and geo-location services. On their own, any of these solutions could have been a standout success. But combined, SWAGG struggled due to technological limitations, brand expectations, and economic assumptions.

Technology: As already shown, the technology was being invented as the team was developing the product. These new features were meant to entice merchants, energize shareholders, and drive users to the app. The innovations were just at or beyond the bleeding edge. This led to a clunky user experience for merchants and consumers.

Brand Expectations: SWAGG The brand promised a Ferrari. But the product? More like a Civic — no frills and reliable. It was billed as this flashy, edgy brand. This was great for concerts and generating what one marketer called “errational excitement” among consumers, but, as covered earlier, it was a miss for most merchants. At its core, SWAGG was a gift card payments and rewards app, not a revolution. So when the gates opened, all people found were empty shelves.

Economic Assumptions: The core assumption for SWAGG — that the wall of gift cards at checkout would become a hoard of users in the app — was shaky. The team believed that people would buy and manage gift cards multiple times a year from their mobile phone, and merchants would pay for the privilege of targeting them. But unlike card networks or Apple, they had no ability to enforce fees or adoption.

The problem was that the wall of gift cards didn’t require the checkout lane to have a relationship with each and every merchant on that wall. One aggregator — like Blackhawk or InComm — manages the merchants while the retailer with the wall of gift cards manages getting consumers in the door. Turns out, winning over the merchants is harder than building the tech.

Lots of Leaders, But Little Leadership

The extensive list of ideas and capabilities reflected the innovative product and business development teams. However, it also shows a lack of focus and guidance from the leaders of the organization. Lulled into a false sense of security by being part of an organization so big, the team didn't understand how perilous the situation was. By the time Fabiano stepped in to lead the group, the ship had already begun sinking.

Leaders in sales, product, strategy, engineering, and upper management were all working to solve the problem. The sales team was working to sign clients while product and engineering teams were busy creating solutions at lightning speed. The strategy was being adjusted with each monthly flight between Qualcomm HQ in San Diego and SWAGG HQ in Atlanta. As 2012 came around, it became increasingly clear that the mobile banking and payment premise wouldn’t work.

The Legacy of SWAGG

SWAGG and Outlier were folded into Pai before being absorbed into Qualcomm Retail Solutions (QRS) in 2013. Of all the solutions spawned from SWAGG developed, it was the geofencing and proximity tech that would find the most lasting success in QRS. The group shifted focus to developing smart posters and bluetooth beacons. Then in 2014, the division was spun off as Gimbal — the bluetooth beacon manufacturer.22

SWAGG failed. But its DNA lives on — not in its app, but in how the world pays today:

The RAN approach pioneered by the team helped launch modern tokenization.

QR-based POS integration shaped merchant-driven payment systems.

The lessons traveled with the team — into the foundations of Google Pay.

The Builders Move On

The members of the core Firethorn and SWAGG teams would go on to develop solutions across the payments and fintech industries. To close, I want to highlight three of those team members who most made this post possible:

Frank Young went on to be a core part of the Google Pay founding team. He then went on to be Chief Strategy Officer of Merchant at Global Payments and is now a Senior Advisor at BCG.

Robert Dessert remained at Qualcomm until 2018 leading long-term strategic research. He and I would cross paths at Truist where he served as Director of Corporate Strategy. He’s now a Strategic Advisor for Toffler Associates.

Aidoo “AO” Osei leaned into the emerging Internet of Things (IOT) trend at Qualcomm, becoming Director of Business Development for the division. After a stint at Intel, AO would land a role as SVP of Product Strategy at Global Payments.23

Ultimately, technology doesn’t win on brilliance. It wins on distribution, trust, and ease. That’s the real legacy of Firethorn: a reminder that payments innovation always follows the path of least resistance.

VII. Epilogue: History Rhymes

Fulfilling the Mobile Wallet Dream

In 2008, Firethorn tried to build a mobile wallet. The tech was too early, the merchants weren’t ready, and Apple had yet to enable NFC. Though the SWAGG solution never took off, it represented a leap forward in mobile payments. One paper that analyzed the technical development of mobile payments cited Dessert and Monahan’s patents as “[a key step] on the main path of technological development.”

The Firethorn and Qualcomm team changed the trajectory of mobile payments by by turning decades-old ideas into real, foundational technology. This locked-in Qualcomm’s competitive advantage in mobile payments for the following decade.

Firethorn’s greatest flaw was that they never controlled the rails — instead relying on carriers or device manufacturers — and without that, even brilliant technology couldn’t scale. In contrast, Apple Pay shipped pre-installed in 2015. That’s the difference between a product and a platform.

But even then, Firethorn pops up. Apple Pay was live thanks in part to the technology developed by Firethorn & licensed by Qualcomm — tokenized card wallets and integrated NFC payments. The same building blocks, just at the right time with the right control.

Executing Payments + Real-Time Ads

In an announcement tailor-made to coincide with this write-up, PayPal recently announced the launch of PayPal Ads:

“PayPal Ads will deliver insights, based on scaled shopping intent and transaction data for relevant users, that will allow brands to create dynamic ad messaging and full-funnel campaigns that drive business growth. Brands will then be able to measure the return on investment and impact to market share. The solution enables interested PayPal users to discover relevant brands and products that enhance their shopping experience, while also helping merchants grow their business.”

This is just one of the solutions SWAGG brought to market — though they had built for in-person and mobile commerce. In 2010, the world wasn’t ready. It remains to be seen whether the timing and tech are aligned. Who knows? Perhaps PayPal will succeed where Firethorn and SWAGG failed.

One Last Thing

SWAGG was an ambitious attempt to redefine mobile commerce, but it faced insurmountable challenges in merchant adoption, technical execution, and shifting market forces. These appear obvious in hindsight, but were hard to foresee at the time, and made even more difficult with the pressure to deliver financial results.

Just as then, today’s environment is full of similar challenges

While the product ultimately failed, its core ideas lived on in Google Wallet, Apple Pay, and today’s mobile commerce platforms. If you take away nothing else from this story of innovation, success, and failure, take these lessons from the guys who lived it:

Own the rails. Firethorn didn't control the mobile platform like the carriers or later device manufacturers. And in payments, as in all tech, those who control the rails decide who gets to ride.

POS change is hard. Retailers need seamless, low-friction integrations. Consumers need simple, reliable experiences.

Hype doesn’t equal adoption. Big budgets, media buzz, and epic launch events don’t guarantee real-world traction.

Stay focused. Early on, find where you add the most value and optimize for it. Save the flashy add-ons for day 2.

Consumer trust matters. Apple Pay and Google Pay succeeded because they simplified security and onboarding.

Timing is everything. SWAGG’s ideas (scan/tap to pay, digital wallets) eventually became mainstream—just not on their timeline.

Payments innovation follows the path of least resistance.

Firethorn’s 2007 Board of Directors reads like a “who’s who” of payments and telecom. Aside from CEO Tripp Rackley, the board featured:

Charles Brewer: Founder of MindSpring, later acquired by EarthLink — making it the second largest internet service provider (ISP) in the country.

Dave Dorman: former chairman and chief executive officer of AT&T. Was also on the board of Motorola, one of the largest mobile device manufacturers at the time.

Gene Gabbard: An investor and inventor responsible for developing time-division-multiple-access (TDMA), the tech used to power 2G communications in most digital wireless phones and global satellite systems.

Paul Garcia: CEO Global Payments — took the company public and ran it from 1999 to 2013. I wrote more about him and that transition here.

Campbell Lanier III: Co-founder ITC holdings which sold Powertel to T-Mobile. Also funded and was the largest shareholder in EarthLink. He passed away last year, but did a wonderful Ted Talk back in 2018.

John Stanton: co-founded three top-10 wireless operators, including Western Wireless (Alltel), where he served as Chairman and CEO. Also served as Chairman and CEO of VoiceStream (later T-Mobile). He is now the chairman of the Seattle Mariners.

For a corollary, think of them as the ancestors of Twilio. They enabled banks to access carriers, managing the relationships for both parties.

Accounting for about 10% of all US deposits at the time, Firethorn’s network included Wachovia ($314 B), SunTrust ($114 B), Regions ($88 B), Synovus ($21 B), FirstBank $0.9B), and BancorpSouth ($10 B).

In an alternate universe, Firethorn becomes Plaid for mobile. However, this idea was still years from being relevant and the phone was the wrong platform for that era.

They were also architects behind the BREW mobile operating system used by Firethorn and virtually every other mobile app developer at the time.

Pre-App Store, apps could be developed, but you had to download them like third-party software directly from the developer. This is how BofA got on the iPhone first. Seeing the obvious threat to control and security, Apple made plans to launch the App Store.

It also set the stage for Apple and Google to later dominate mobile wallets themselves, but we’ll get to that another time.

Meeting these standards enabled Firethorn's merchant customers to process contactless card payments and other POS transactions, such as gift cards and loyalty rewards.

Patent application US20100125495A1, titled "System and Method of Providing a Mobile Wallet at a Mobile Telephone," was filed in November 2008, and published in May 2010.

I should note that the Firethorn team was not working in a vacuum when it came to using QR codes for payments. Two innovative engineers at Symantec, Shaun Cooley and Andy Payne, created a system for online QR code payments in 2010 — about a year after the Firethorn team developed the solution for physical POS.

This realization is similar to the one Jack Dorsey and the Square team had about card readers. When a card is swiped, the magnetic strip passes over a sensor that converts the varying magnetic field into electrical impulses. This is the same technology that powered audio cassette tapes. The Square team realized that if a cassette reader could convert music into electrical signals that could be played through a headphone jack, then they could convert the electrical signals from a card swipe and pass it back through that same connection.

Team Highlight: Scott “The Guy” Monahan

While the rest of this story follows Spark, it’s worth a brief aside to highlight an incredibly talented individual, Scott Monahan. As Dessert puts it, “without [Monahan], the world of mobile payments would look very different.”

The stories of genius developers are often hyperbolic, but this doesn’t seem to be the case for Scott Monahan. Monahan was the Software Architect behind Firethorn‘s mobile payments platform — the one who took Dessert’s sketch and made it real.. According to the team, Monahan more than anyone else was responsible for taking mobile wallets from notebook page to functional product.

Dessert explained, “[Monahan] was the guy who got [mobile payments] to work before anyone else could figure it out.” Monahan engineered the backend solution and integrations needed to turn a QR code embedded with a BID and TID into a virtual card number that was processed through the network in less than five seconds. This clever trick solved the key issues of NFC and Bluetooth enabled payments.

Some anecdotes on Monahan:

A common phrase among the team was “if it’s impossible, give it to Scott.”

“In Building N of Qualcomm’s San Diego headquarters, two floors below the executives, there was a vending machine with a credit card reader. Scott turns to me and asks if I wanted a soda. I said, ‘sure.’ So he asked for my credit card and said, ‘watch this.’ He types in the information, and out pops my soda. Vending machines are just POS systems without a human behind them. He had tapped into the vending machine via a backdoor and let us order whenever we wanted.”

“He created the Amazon core payment system over a weekend. Over the course of 7 years, it was only ever down for three seconds.”

D.H. Shin; Towards an understanding of the consumer acceptance of mobile wallet; Comput. Hum. Behav., 25 (6) (2009), pp. 1343-1354; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563209000958/pdfft?md5=a309811c7c636ec1d10340141ecb9580&pid=1-s2.0-S0747563209000958-main.pdf

This is to say: For 70% turnover, imagine a room of 10 people on January 1st, 7 would have left by December 31st. For 120% turnover, Walmart would have lost that whole group of 10 plus an additional 2 that they hired to backfill the positions.

One of the deal-makers from mFoundry team, Jon Squire, would go on to found CARDFREE in 2012. CARDFREE integrates with stored value (gift card) systems through a merchant’s existing POS system. The system not only enables cards but also offers, rewards, points, and other loyalty programs. Their first big client? Taco Bell.

Rodney Aiglstorfer was the software engineer behind most of mFoundry’s patents at the time. His contributions enabled multi-factor authentication, secure data transmission, and off-device application processing for mobile phones. For more, the list of mFoundry Patents can be found here: https://patents.justia.com/assignee/mfoundry-inc

2011 10K, page F-18 (79 in the PDF). Full quote:

During fiscal 2011, the Firethorn division in the QWI segment introduced a new product application trademarked as SWAGG. The initial consumer adoption rate of SWAGG had fallen significantly short of the Company’s expectations, and as a result, the Company revised its internal forecasts to reflect lower than expected demand and reduced the Firethorn cost structure. Based on these adverse changes, the Company performed a goodwill impairment test for the Firethorn division, which was determined to be a reporting unit for purposes of the goodwill impairment test. The goodwill impairment test is a two-step process. First, the Company estimated the fair value of the Firethorn reporting unit by considering both discounted future projected cash flows and prices of comparable businesses. The results of this analysis indicated that the carrying value of the reporting unit exceeded its fair value. Therefore, the Company measured the amount of impairment charge by determining the implied fair value of the goodwill as if the Firethorn reporting unit were being acquired in a business combination. The Company determined the fair value of the assets and the liabilities, primarily using a cost approach. Based on the results of the goodwill impairment test, the Company recorded a pre-tax goodwill impairment charge of $114 million in other operating expenses in fiscal 2011. Subsequent to the impairment, $40 million of goodwill remained for the Firethorn reporting unit.

Gift Card Accounting 101

Whenever a gift card is loaded with funds, those funds become a liability for the company. Although the company has the cash, it also means that at some time in the future, they’re liable to pay out that cash in the form of a purchase. This is bank accounting 101. Gift cards throw in additional complexity because of breakage escheatment.

If these balances go unused for long enough, they become unclaimed assets. Depending on the jurisdiction, the balances may become breakage (i.e. free money) and flow to the company. However, in some states those unused balances become escheat and become property of the state while they seek out the rightful owner. The complex web of jurisdictions and codes makes managing a gift card program a headache for any company.

The process for creating a RAN was developed by American Express and is used by license across a variety of card-based platforms.

The technical mechanism used was to limit the MIDs and even the TIDs where a card could be redeemed. This is primarily how your HSA, student campus, fleet or rebate cards function. Some HSA programs today are sophisticated enough to limit transactions down to the per item level! Learning this finally answered a long-burning question for why my BuzzCard needed a separate terminal at the Tech Square Waffle House.

To win the deal, the team built an entire online ecosystem for a fake denim company. The app featured a selection of jeans and jackets and integrated the offers & targeted promotions features announced in 2008.

The BK App featured here was part of the Pai initiative. The app, however, had some challenges on the business end. One insider explained:

In a meeting with BK's holding company in Miami, their management team said, "I'll sign your contract now, today, under one condition: We want exclusivity for 1 year."

[The Pai] retail funnel looked strong enough that we declined it - we wanted Pai to become a ubiquitous solution. But obviously...it was not to be. The funnel — which included Starbucks — dried up, and we were left with no one.

NFC payments didn’t see wide adoption in the US until half a decade after SWAGG was wound down. By then, the device manufacturers like Apple and Samsung had locked down the infrastructure.

As part of researching this series, I had the chance to interview Steve Statler, better known as “Mr. Beacon,” host of the Mr. Beacon Podcast. He’s just as affable and knowledgeable live as he is on the show. Steve reinforced many of the points AO, Frank, and Robert described. He’s the source for the quote “Being early is the same as being wrong”

His office door opens to my desk at work, which is how we were introduced. He’s the one who pitched the idea of doing this write-up to Frank and Robert. This story wouldn’t have been documented or as enriched without our quick chats.