Philosophy on Payments | Part 3

Transforming America's payment landscape from pen and paper to bits and bytes.

The rise of the Federal Reserve

As the banking panics continued, major clearinghouses time and again served as the backstop against financial collapse. Between 1850 and 1907 there were five such “panics” which, aside from the panic of 1857, saw clearinghouses stepping in as the lender of last resort to struggling member banks. This served to strengthen confidence not only in the financial system, but in the private clearinghouses as a necessary bulwark against ruin.

Following the last of theses panics in 1907, the half-century of lessons learned and trust built by these private institutions were rolled into the Federal Reserve via the Federal Reserve Act of 19131. The act gave the Fed authority to step in and take the role of clearinghouse for the nation — specifically sections 13 and 16:

Section 13, Subsection 1: “Any Federal reserve bank may receive from any of its member banks, or other depository institutions, and from the United States, deposits of current funds in lawful money, national-bank notes, Federal reserve notes, or checks, and drafts, payable upon presentation…”

Section 16, Subsection 13: “Every Federal reserve bank shall receive on deposit at par from depository institutions or from Federal reserve banks checks and other items…”

For an exhaustive (and exhausting) breakdown of the Fed’s early clearing system, see Section 10 of “The clearing and collection of checks”, by Walter Earl Spahr (1926).

These enumerated powers combined with certain characteristics of central banking to make the Fed’s payment system different:

Top-down government mandate vs. a bottom-up consortium of banks

Nationwide vs. regional scope

Operated payment systems at cost

An early target of the Fed’s new powers was the practice of discounting checks, “non-par banking,” which had been around for at least a millennium at this point. Through the powers in Section 16 and by serving as a universal correspondent bank, the Fed sought to make $1 = $1 no matter the bank or city. While a Supreme Court ruling would set this back, they did the next best thing — disallowed non-members from using the system unless they settled at par.

Additionally, the restrictions on interstate banking made conducting interregional trade via check expensive and time consuming. The number of correspondent banks, each taking a fee along the way, made most transactions impractical. So even though the use of the Fed’s payment system wasn’t required by law, many banks decided to use Fedwire as it was low cost, fast, and nationwide.

Turning to Fed Governor Lael Brainard speaking in 20182

Fostering a safe, efficient, and widely accessible payment infrastructure has been a crucial aspect of the Fed's mission from its founding in 1913. By creating a new core infrastructure for clearing and settling checks, the Fed was able to boost confidence in banks and America's payment system, ensure Americans received the full value of their checks, and speed up payments.

That was the first, but not the last, time that the Fed played a central role in transforming America's retail payment system…

Defusing the (paper) bomb

The years between 1913 and 1968 saw an explosion of growth in the U.S. economy (with one notable exception) along with several galvanizing moments. The economy expanded rapidly during the 1920s only to see hundreds of bank and clearinghouse failures in the 1930s. It then roared back to life during the 1940s while prosperity and consumer spending saw it reach ever higher through the 1950s and 1960s.

The increase in economic activity meant more money was flowing around and into banks. With more money in the bank, Americans increasingly turned to their preferred payment method, checks. By 1960, Americans were writing 14.5 billion of them annually and showed no sign of slowing down.

“One of [your grandfather’s] duties at the end of every day was to walk the bag of checks from Natchez First Federal Savings and Loan to the local bank Britton and Koontz National Bank two buildings down the block every night so they could be cleared.” — Mom

To handle the deluge of paper, 1 in every 6 bank employees was assigned to manually sorting and processing checks — each one varying in size, format, and even shape.3 Adding to the headache was the fact that accounts were organized by name at a branch level.

To solve this, several banks (including California’s Bank of America) began turning to the new field of computing for relief.4 The computer scientist’s first recommendation was to do away with ordering accounts by customer name and instead assign each one a unique number.5 These numbers would then be printed on standardized checks as a decided upon by the American Bankers Association and Federal Reserve.

With sorting and identification solved, the last challenge was reading a check into the mainframe computers which were revolutionizing the world of finance. The two solutions — IBM’s barcodes and Stanford Research Institute’s magnetic ink character recognition (MICR) system — were each considered with MICR winning out in 1956 because it was human readable6.

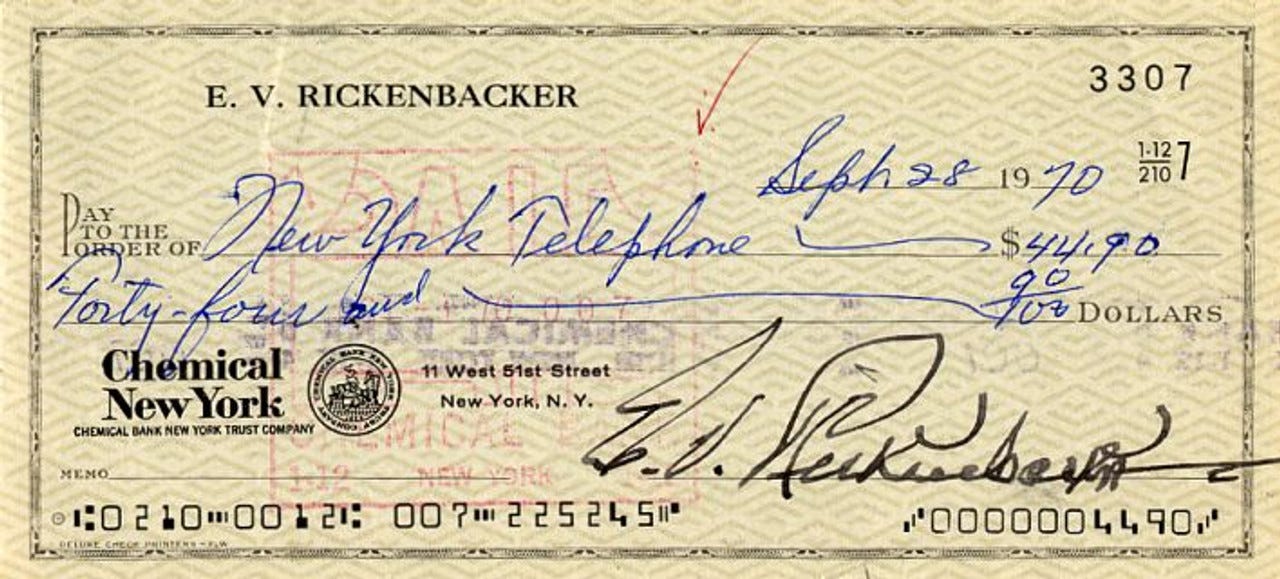

The checks now took the familiar form we see below:

How much currency is changing hands: $44.90 (“000004490” in bottom right corner)

Who is paying: Chemical New York, routing number 021000127, from account 007225245 owned by Eddie Rickenbacker

Who is receiving the payment: New York Telephone

A form of authorization: Rickenbacker’s signature

What it’s for: the memo line is blank, so we don’t know for certain. Perhaps a phone bill?

The data processing department of the two community banks I worked for had several of the machines that people (mostly all women in the processing department) sat at all day keying in the amounts and then running the check through the machine to add the magnetic ink amount in the corner. — Mom

The MICR lines allowed for checks to be processed with computers, however, the system still required someone to look at the check and type in the amount on the check.8 Even leaving manual processing aside, the settlement and clearing still relied on the centuries old laws that a check be physically presented to the bank before it could be settled.

This holdover was important as it reduced the risk of fraud, but it meant that “the average check [by 1971 is] handled ten times between the time it is written and the time it finally operates as a draw upon its account...”9

To overcome this last vestige of the past and truly enter the digital age, parallel studies across the country were conducted all with the same goal. But rather than SCOPE (which eventually became CACHA then WesPay and inspired NACHA)10, we’re going to take a look at the less talked about experiment taking place in the country’s networking hub.

A Checkless Terminus

Long a hub for logistics, by the late 1960s Atlanta was home to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph, National Data Corporation, and Dr. Paul Han, an enterprising professor at Georgia Tech’s School of Industrial Management. 11

Han was an optimist who saw the looming check crisis and decided to do something about it and bring about a “checkless society.” He wasn’t alone in this desire — the idea was prevalent in the 1960s with dozens of bankers, scholars, and futurists theorizing what it would do for society. 12

What made Han unique was his timing and ability to garner support for his idea. The Federal Reserve of the 1960s and 1970s had enthusiastic governors like George Mitchell who were pushing for the electronification of payments. Coupled with the Atlanta Fed and its Senior Vice President Brown Rawlings being three blocks from campus and funding from the Georgia Tech Research Institute, Prof. Han and several graduate assistants launched what would later be called the Atlanta Payments Project.13

The Project was split into four phases to be completed in rapid succession:

An Analysis of Payments Transactions (1969)

Payments Flow Data (1971)

General Systems Design and Analysis of An Electronic Funds Transfer System (1972)

A Technical, Marketing, Organizational and Cost Evaluation of a Point-of-Sale Terminal System (1972)

The end goal was a framework for the United States’ first electronic check payment network.

Following the death of Prof. Han in 1971, the project was handed off to Dr. Allen Lipis who would see the project through to completion. In need of additional funding and industry expertise, Lipis brought four of the largest banks in Atlanta14 together with the Atlanta Fed to complete Phases 3 & 4.

Phase 3 came in at 1,300 pages of detailed information on electronic funds transfers and formed the technical backbone of the Fed’s ACH system launched in 1973. Phase 4 was of similar length and would influence the POS ATM cards of the mid-1980s.

But what were they proposing to do with all these findings? Dr. Lipis had four immediate use cases for electronic payments, see if they sound familiar:

Direct Deposit of Payroll & Benefits: Funds automatically arrive in a person’s account, no need to visit a bank and deposit a check on payday

Automatic Bill Pay: No more checks walked over to the utility office or mortgage broker, instead they would automatically bill you for the amount (previously shared via mail, of course)

POS Transfer of Funds: Debit Cards rather than credit or ”charge” cards, eliminating check float and lack of check acceptance by merchants outside a bank’s core market.15

Check Imaging: Recognizing that the system couldn’t eliminate checks outright, this allowed for checks to be scanned and turned into electronic funds transfers.

In time, all of these ideas would come to pass, but it wasn’t without intense resistance:

60% of Atlanta’s households were opposed to direct deposit with only 29% supporting the idea. 81% of businesses also opposed the idea, but “if their responses are only a reflection of employees’ attitudes, however, the situation might be changed.”16

70% of households opposed pre-authorized payments

So why the resistance?17 As with anything novel, it came down to a lack of trust, understanding, and desire to change old habits.

Changing Tides

Throughout that history no technology has ever precipitously replaced its predecessor; changes, spawned and modulated by shifts in underlying cost structures, have taken place gradually. — Edward Dauer

What does happen is that its opponents gradually die out, and that the growing generation is familiarized with the ideas from the beginning: another instance of the fact that the future lies with the youth. — Max Planck

There were two major sources of distrust in the proposed system: one behavioral and the other legal.

The legal question — is an electronic message a valid question — was short-lived. Banks had been relying on the Fedwire system since 1918 and electronic records had been generally accepted as valid sources of record. The behavioral change would take several generations as memories of bank collapses and failures during the 1930s lingered in the American psyche.18

Convincing people to cede (perceived) control over their paycheck could be done with educational campaigns about the reduction in cost and potential time savings.19 The problem with this is that humans aren’t profit maximizing automata — we are homo sapiens not homo economicus. Instead, the Federal Reserve went with a different strategy: brute force.

In search of an initial user for the network, the Fed turned to a large, familiar (and captive) customer: the US Government. In September 1974 after pushing by Fed Governor George W. Mitchell, the US Air Force began paying 45% — 270,000 employees — via ACH. He was “undeterred by the fact that neither the Air Force, Federal Reserve System nor banking industry were prepared.” Governor Mitchell, considered the father of electronic payments, was going drag the U.S. kicking and screaming into the era of electronic payments.

Rather than waiting for everyone else, Governor Mitchell continued to push ACH as the replacement for checks. The Treasury Department and Social Security Administration followed the Air Force in 1975. That same year, the gates were opened to all banks across the country to participate using the Fed’s 42 Regional Check Processing Centers (RCPCs) to handle the rolls of magnetic tape containing payment information.

The rolls of tape were initially trucked and flown around the country through the Fed’s existing check settlement infrastructure. A secure, long-distance communications network would be implemented in the 1980s. The rolls of magnetic tape contained the same payment instructions as a check but were standardized and much less human readable. Although it’s less friendly than its physical check counterpart, we can still decipher the text file using the payment instructions framework laid out in the last post:

The transaction instructions are on lines 1 through 4, with my own emphasis added for clarity.

101 02100002 10000000000 180515 0735 A09410 JPMORGAN CHASE

QANAMEFORCOMPANY

5220

111111111111111111110000000000 PPD Payroll MAY 30 180530

MAY 30180530 1021000020000001

632 081904808 12345678901234567 0000010000 123456789012345 MARY JANE

1000000000000001

705 PAYROLL PAYMENT FOR FIRST WEEK OF MAY

00010000001How much currency is changing hands: $100.00 (displayed as “0000010000”)

Who is paying: JPMorgan Chase, routing number 02100012, from account # 10000000000 owned by QANAMEFORCOMPANY

Who is receiving the payment: Bank of America, routing number 081904808, to be deposited in account # 12345678901234567 owned by Mary Jane

A form of authorization: The file control record, several check variables sprinkled throughout (like the trace number “1000000000000001”

), and the fact that it was securely transmitted from the bankWhat it’s for: Payroll payment for first week of May

This jumble of numbers and letters was going to revolutionize recurring payments, but despite all their best efforts "…consumers by the thousands [had] built up resentment against the mistakes and impersonal narrowness of computerized operations.”20

With the Fed subsidy ending in 1985, their ACH network was set adrift and left to fend for itself against other market competitors, physical and electronic. This led one Fed commentator to call it “a network whose potential has not yet been realized” while another called it “an elusive dream.”21

Realizing that dream took several catalysts, and the one I’m focused on originated from a surprising source: the FOMC.

Gaining Ubiquity

My first boss out of college told me: “Incentives drive behaviors.” In the late 1980s interest rates, the determining factor of a bank’s success, skyrocketed to 14.6% and remained above 6% under Paul Volcker’s FOMC leadership. His campaign to squash the Great Inflation coincided with the “bomb” of check volumes finally exploding. These simultaneous events created the incentive for banks to get on board with electronic payments like ACH — float.

Float, in this context, is the time between a check being written and the funds being deducted from the account. While a check was “floating” the funds were not available to be spent by the payee and the payer still held the funds in their account. This was an inconvenience for the payee but could be a boon for the payer as it might mean that additional interest could be earned or that overdrafting an account22 (spending more than you had) could be avoided.

The payer and their bank were able to earn interest on the account for the 2-5 days that it took to clear a check. While not an issue for personal transactions, the loss on the billions of dollars in payroll and benefits represented a sizable opportunity cost for banks. This along with an aggressive advertising and education campaign from the Fed would lead more banks to join the network and encourage their customers to switch to digital payments during the 1990s.

With sufficient levels of acceptance achieved, the Fed — in a stroke reminiscent of its actions around check processing 80 years earlier — used its powers to mandate that banks in its payment network be ready to accept electronic transfers in March 1994.23 They did this by amending Regulation E to bring benefit programs under its jurisdiction, growing the network until it overtook check volumes around 2008.

But then nothing changed. There were innovations in ways ACH data flowed around the country and card networks stepped in to provide real-time transactions, but the Fed made no change in the way it moved money — it certainly didn’t bring about a “checkless society.”

If we look to the private sector operator24, TCH (The Clearing House; the successor of the New York Clearing House from the last post), replicated the rails introduced by the Fed:

Fed Check Clearing → CHECCS (Clearing House Electronic Check Clearing System) operated by TCH subsidiary SVPCO (Small Value Payments Company)

Fedwire → CHIPS (Clearing House Interbank Payments System)

note: CHIPS settles via Fedwire. The CHIPS messaging service just allows banks to net transactions, saving money on transfer fees.

FedACH → EPN (Electronic Payments Network)

It wasn’t until 2013 — almost 50 years since the Atlanta Payments Project began — that another Fed Payments study would take place. The result would be the United State’s first new payment rail, RTP. Rather than coming from the Fed directly, this one came from the private sector and, as of this writing, is the most modern payment rail in the US.

We’re now at the present day which means we’re also at the end of this look at “things as they were”. In the next post, we’ll take a look at the current landscape in the US as well as glancing out into the world to see what was going on. I hope you’ll stick around for it!

If you want to get caught up on this series check out my previous posts.

This act goes by another name: the Glass-Owens Act. It was co-sponsored by Carter Glass, Democratic Senator from Virginia who, among some questionable other things, also co-sponsored the Glass-Steagall Acts during the Great Depression which created the FDIC, cleaved investment banking from commercial banking, and pretty much killed interstate branch banking.

From Governor Lael Brainard’s speech “Supporting Fast Payments for All” given at the Fed Payments Improvement Community Forum in 2018

There have been several instances of scraps of paper along with golf ball and champagne bottle-shaped checks being issued as valid checks.

In information computing, these unique identifiers are known as “keys”. Keys allow you to quickly reference a database table. There’s a large body of research on the optimal way to assign keys and search for them, but that’s outside my scope of expertise.

We still use this by the way, and you can see it for yourself. Take a check from your checkbook (assuming you still have one) and hold it over the edge of a table. If you bring a strong magnet towards the numbers on the check, you’ll see the paper move.

The same trick works for US currency notes and is one of the ways a vending machine can tell your bill is real. This was my exact 4th grade science project — so I guess the fact I ended up interested in payments isn’t surprising in retrospect.

The Federal Reserve made MICR mandatory in 1967. Though this was more of a formality as over 97% of checks already featured the technology by 1962.

This is still a valid routing number for JPMorgan Chase, the successor to Chemical Bank.

The technology that transformed handwritten amounts into computer data was actually developed by the US Post Office around this time. Why? Because the volume of mail was growing similarly out of hand.

The details of this story and how it relates to Georgia Tech can be found in the Winter 1972 Alumni Magazine. https://issuu.com/gtalumni/docs/1972_50_2/10

Bank of America put together ERMA (Electronic Recording Machine-Accounting) to automatically process physical check in 1955. However, by 1968 the physical volumes of paper were too large for ERMA to manage. To combat this, the Los Angeles and San Francisco clearinghouse associations joined together and created the Special Committee on Paperless Entries (SCOPE). SCOPE’s findings would eventually become the California Automated Clearing House Association in 1972 before becoming WesPay in 1993. (Source)

For a detailed account of ERMA’s development, check out Highways of Commerce Chapter 8, Hannah H Kim’s post in Increment, or GE’s 1961 sales meeting

It’s now the Scheller College of Business. Tech has a rich history in industrial engineering and management which you can read about here.

Bátiz-Lazo, B., Haigh, T., & Stearns, D. (2014). How the Future Shaped the Past: The Case of the Cashless Society. Enterprise & Society, 15(1), 103-131. doi:10.1093/es/kht024 https://www.imtfi.uci.edu/files/docs/2013/payments_salon_reading_batiz-lazo_haig_stearns_how_the_future_new.pdf

For more on the Atlanta Payments Project, check out “How Georgia Became a Payments Mecca” (2015) by Trevor Williams or “Development of Electronic Funds Transfer Systems” (1976) by William C. Niblack.

The banks were Citizens & Southern National Bank, First National Bank of Atlanta, Fulton National Bank, and Trust Company of Georgia.

It doesn’t fit with the overall narrative arc here, but the concept of check float comes up a LOT in the literature.

Personal Finance. Elizabeth M. Fowler. New York Times. July 15, 1971. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/07/15/archives/personal-finance-bank-customers-appear-to-oppose-the-concept-of-a.html

It was immensely complicated to operate and required all banks involved to collaborate for the better good of the banking system rather than their individual needs. Mutual cooperation continues to appear in this story as it is a prerequisite for the institutional trust required to implement such measures.

Nearly half the US population in 1970 was born prior to 1940, meaning that the vast majority of Americans were wary of banks to begin with.

The processing costs for banks would go from $0.16-$0.20 to as little as $0.008 — a +95% reduction. That’s just the direct processing costs. If you consider the cost associated with float, the savings quickly approach +99% (source)

Quote from Dr. Lipis can be found in the 1970 GT Alumni magazine.

Frisbee, Pamela S. "The ACH: an elusive dream." Economic Review Mar (1986): 4-8. Link to pdf

“The first bank I worked at made a significant amount of money off of these check-related fees. Our CFO used to share in staff meetings that ‘we had the best worst check writers in town.’” — Mom

All the other operators began consolidating in the 1930s and then again in the 1990s. This left The Clearing House, for better or worse, as the only player in private market. Owned by some of the world’s largest banks, it is designed to act for the benefit of all financial institutions. But as we’ll see in the roll out of their RTP product, TCH has only been able to garner support of 300 out of the +10,000 banks and credit unions across the USA.