Philosophy on Payments | Part 2

This is not a short post - it's 6,500 words - and it does get technical in places. Grab a coffee, because we're journeying from clay tablets to clearing houses.

This is part of a series, you don’t need to have read part 1 to understand this post, but it provides some context for why I’m writing it. This post also only covers up until clearing houses — I felt that cutting it here will be better for the story and your time.

From Clay to Clearing House

Before starting this journey from the past to the present, I’m laying out a framework in which to examine the evolution of payments as we build towards RTP.1 I’ve provided a framework below, but understand that there are, and always will be, multiple ways to do things.

What is a payment instruction?

A payment instruction is, at its core, a promise for someone to pay a stated amount to someone else at a time in the future along with details related to that promise.

Instructions like this have likely existed as long as human civilization2 and often took the form of an oral agreement secured by the trust between two individuals.3 Over time, written communication was established and regular, long-distance trade began.

With long distance trade — “long” here could mean anything from 30 to 300 miles — and writing, we see the first written payment instructions. They all had these key elements:

How much currency or commodity is changing hands

Who is paying (sometimes called a debtor, payer, drawer, or maker)

Who is receiving the payment (creditor or payee)

A form of authorization (typically a seal or signature)

What the payment is for

Some early payment instructions which take this format have existed since at least 2000 BC and likely go back as far as written language itself.45

Bronze Age payment instructions

At the Bronze Age site of Kanesh6, a trading town in central Turkey, hundreds of clay tablets dating to between 2000 and 1600 BC were discovered detailing the commerce and trade which was occurring in the region in meticulous detail. Among them were tablets which featured one of our earliest examples of a payment instruction:

In accordance with your message about the 300 kg of copper, we hired some Kaneshites here and they will bring it to you in a wagon... Pay in all 21 shekels of silver to the Kaneshite transporters. 3 bags of copper are under your seal.

Using the definitions above, we can recode this 3,600-year-old message as:

How much currency is changing hands: 21 shekels (about 1.7 oz.) of silver

Who is paying: the unknown recipient of this tablet on behalf of the merchant

Who is receiving the payment: the Kaneshite traders

A form of authorization: a seal

What it’s for: 300 kg of copper

This basic form of payment instructions has likely existed as long as there have been merchants buying goods in far off lands. Why? Because carrying that much money was risky, expensive (someone must haul and guard it), and impractical for larger transactions where the terms were not prearranged.

But why didn’t they expand into what we have today? Modern determinism aside, there was a low level of trust between the transacting parties.

The Trade Dilemma

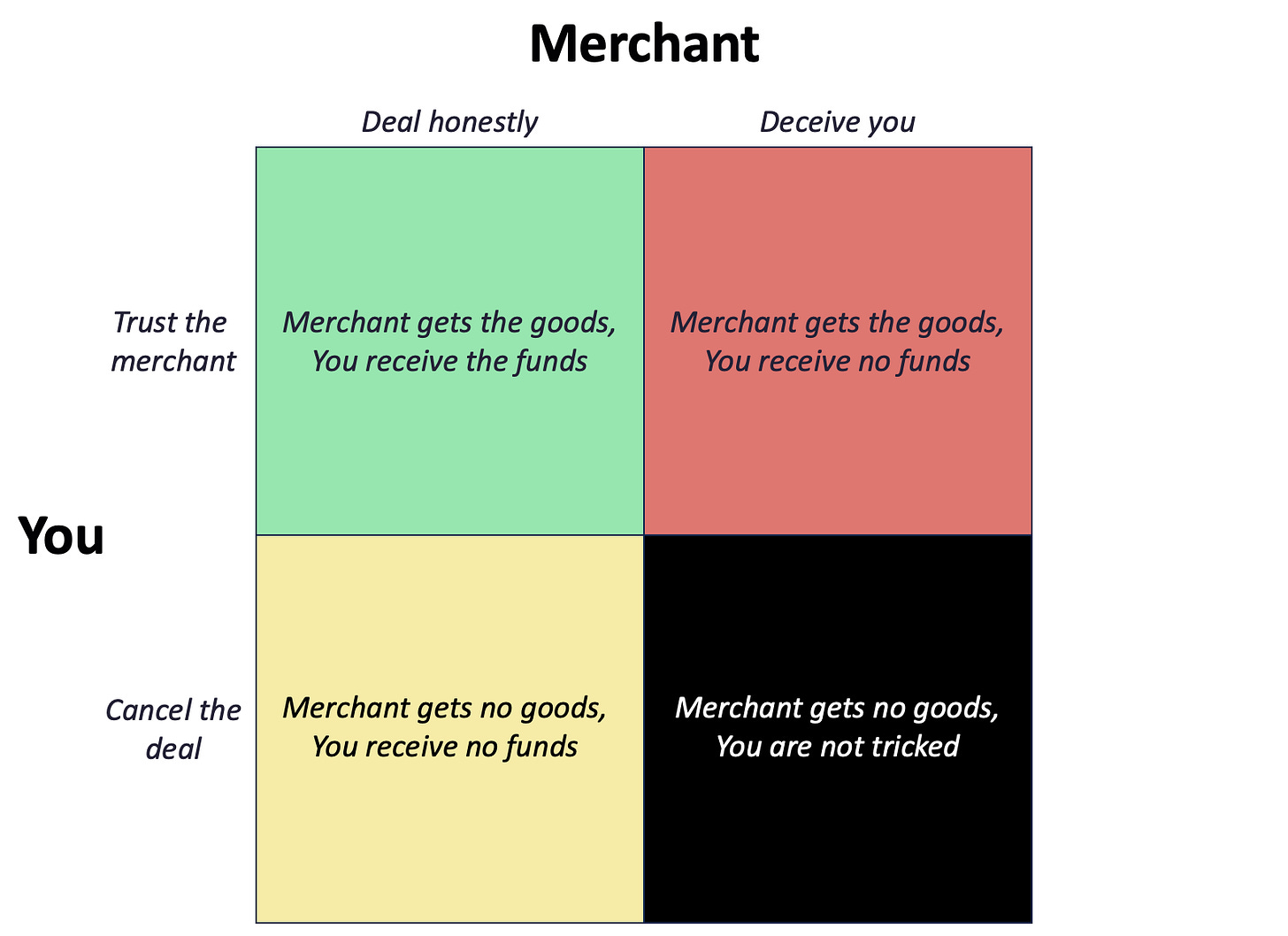

Let’s say you’re closing a sale with someone in a town that you only met that day. After agreeing on a price, you hold your hand out to accept the coins and they hand you…a piece of clay. The merchant insists that the piece of clay contains instructions to their friend in a town on your journey home. And if you just stop by, they guarantee that you’ll be paid.

What would you do? Let’s look at the different choices you and the merchant can make and what the outcomes would be in the graphic below:

The optimal solution depends on how well you know the merchant:

If you know that the merchant is honest in their dealings, then the optimal solution is to trust them and complete the sale (top left).

If they’re suspected of being dishonest, cancel the deal to avoid being tricked out of your wares (bottom right)

But what is the best move when you’ve only just met them and have no prior knowledge? For most of human history — barring times when there was a strong central authority enforcing laws — it was optimal to cancel the deal to avoid the downside risk associated with being tricked and potentially left destitute. Or, to put it in payment terms: for much of human history, the counterparty risk was too high for such payment methods.

To function, the notes we’ve looked at, or indeed any long-distance financial system, require a strong central authority to function. This authority often came directly from the state — the Assyrian kingdom above or, as we’ll see later, a country’s central bank — and occasionally from a religion — temple priests or the tenets of Abrahamic religions.

For millennia, the kingdoms which traded ruling Mesopotamia7 would supply the institutional authority either directly or through state run temples. After each war of conquest had settled, new victor would implement common trade practices and standards across the region. With the standardization of rules and relative peace came increased intra- and inter-regional trade, thus increasing the need for such notes. So long as these two conditions held, credit notes like the ones above would power the trade and commerce of the region.

Nearly three millennia after the copper was delivered, a new power would take its turn ruling the region. Its rulers would combine the authority of past Mesopotamian kingdoms with a religion founded by a former merchant. The melding of historical precedent, religious conviction, and worldly practicality paved the way for the widespread use of what we might recognize as checks.

The Sakk

First seen in the Abbasid Caliphate, the sakk (pl. sukuk), an Arabic word roughly translating to “order of payment“, was a generally standard document which featured the same instructions as the clay tablets above. What makes them novel is the standardization which is why they’re generally considered the earliest example of the modern check.8 To quote historian Eliahu Ashtor9:

The sakk… is a genuine cheque, that is to say an order of payment made through the bank with whom the drawer has an account.

As would be repeated over 1,000 years later with ACH, the sakk’s original use case was for government payments.10 Because it was a payment order coming from the state, the sakk carried a high degree of trust. they could be “cashed” with the state’s bankers. This built trust not only in the newly ascended government, but also in the sakk as a reliable method of payment.

Thanks in part to the stability that came with the Caliphate and the rise of Islamic banking, the use of sakk became mainstream. Merchants and subjects of the caliphate were regularly using sakk as a medium of payment and exchange because of Islamic laws which required free internal trade.

In conformity with the Shari’ah, the [Abbasid Caliphate] adopted and applied the principle of free internal trading, not imposing any restriction on the flow of goods and labour.

_

Furthermore, the government’s free trade principle was extended to external trade too, with both receiving equal tax treatment. 11

With open markets to the east, Western European merchants12, and later armies, came face to face with the Islamic Golden Age. Among the many goods and knowledge exchanged was that of the sakk and, its older, long-distance form: the suftajah.

Suftajah→Bill of Exchange

Suftajah is an Old Persian word brought into Arabic which means “a document written by a person to his representative or debtor instructing him to pay a certain sum of money to his creditor.”13 These formalized documents were the direct descendant of the clay tablets discussed previously. They were intended specifically for long-distance trade and allowed for merchants to avoid the risk of losing money while traveling. If you are robbed of your suftajah, then only the paper was lost.

The trust in the document came from two sources: the reputation of the payer and the knowledge that the Caliphate required bankers who issued the notes to keep detailed records. The threat of state action was enough to clear the minimum bar of accepting the note. If the issuer was not well known or respected, the bill was discounted — rather than receiving 1000 dinar, you may only receive 900. This is what we might call a convenience fee or, more accurately, the “cost of trust”.

The kings and Popes of Western Europe, each accustomed to familiarity and coercion14 as a means of solving the counterparty dilemma, saw in the suftajah a means of potentially replicating the wealth of the Muslim Caliphs and merchants.

So with a few tweaks, the Europeans created what we now call the bill of exchange. Such bills, however, were not used in everyday trade, but served as a means of conducting long-distance commerce.

By the early 15th century, the documents and legal infrastructure necessary to enforce such contracts had been refined to the point where they were being used for interpersonal trade. Using the framework for payment instructions let’s explore an example bill of exchange from 1402:

[Front]

To the noble and wise master Jacomo Gabriel for 300 reals

[the Gabriel merchant seal]

[Back]

In the name of God, amen. 1360, 18th of November in Venice.

Mister Jacomo Gabriel,

I will pay for this first letter in Bruza to Mezo Luio [a relation of] Mr. Bortolamio de Goldia [300] rials, 2 florins per rial, … of which I [used to] purchase here from Mr. Piero Morexini de Santo Antolin [43] books…

Zacharia Gabriel15

Rearranging the message, we see:

How much currency is changing hands: 300 florins at an exchange rate of 2 florins per rial16

Where the currency coming from: Jacaomo Gabriel in Bruza, on behalf of Zacharia Gabriel

Who is receiving the payment: Mezo Luio

A form of authorization: the Gabriel merchant seal

What it’s for: 43 books purchased from Mr. Piero Morexini de Santo Antolin in Venice

What’s important to understand here is that, unlike a modern check which is a credit instrument, a bill of exchange is just that: a bill. To better explain, I’ll borrow from monetary historian Colin Drumm:

When Mezo Luio presented this bill of exchange in to Jacaomo Gabriel in Bruza, he was given ”…the opportunity to ‘draw on’ these foreign balances by ‘drawing’ a bill ‘on’ [Jacaomo, on behalf of Zacharia], which means that [Mezo Luio] is the ‘drawer’ and [Jacaomo] is the ‘drawee.’”

Continuing this:

…The bill of exchange, in other words, is not a demand instrument: upon being presented with the bill, [Jacomo] has additional time to raise the funds to pay the bill (perhaps one or two months), and this period of time, the “usance,” is the period of time for which charging a price would constitute “usury.”

Colin’s original example for how a bill of exchange functions can be found in the footnotes.17 For a more detailed explanation on the precise function and historical context of a bill of exchange as well as their later use in 18th century trade, I would recommend Colin Drumm’s work “Bills of Exchange, Medieval and Modern“.

The trust in this bill of exchange system came first from the merchant’s name and reputation and second from the usance which allowed time for the drawee to gather the funds18. Certain legal protections for drawers did exist but were limited in jurisdiction. Instead, the threat to one’s reputation — the most important form of currency19 — served as a much stronger incentive against defaulting on these notes.

During the three centuries of where the bill of exchange was being adopted across Europe, a simultaneous financial reintroduction was occurring in the trading houses of Northern Italy and the Low Country: deposit banking.

The European Banks

Early banks served to ease commerce by holding funds in deposit, settling transactions between depositors, issuing loans, and investing funds in trade ventures. Initially, these banks were just wealthy and trustworthy men who had received a charter to set up at a lending table, banco di prestiti in Italian.

These banchiere, as they were called, served an important role in local and foreign commerce by providing liquidity and increasing the speed of commerce. In the latter, a banchiere served as the counterparty, that is the drawee, for a bill of exchange

At its most simplified level, when two or more depositors wished to perform a sizable transaction, the group would visit the banchiere and inform him of the transfers which need to take place. The banchiere, upon hearing this confirmation, would open his book and mark the appropriate debits and credits.

This action was little more than an abstraction of exchanging coins, but one that reduced the need for storing large number of coins on hand and made lending easier to manage. The real innovation began when the financing needs of local trade and the practice of written bills of exchange were combined with the deposits in a bank.

Checks as demand instruments

Around the 1400s, the first checks began to appear.20 These checks were often for small sums and made out to local merchants from local payers. Unlike bills of exchange, which carried some degree of counterparty risk and had a built-in time before they were due, a check was payable on demand.

If you showed up to a bank and presented a valid check, then you would be given (but more likely credited) the amount due. No waiting. No usance. Banks were comfortable with this as the payments were local, so they knew well all the clients who might draw upon the deposits. Legal mechanisms — fines, imprisonment, etc. — were also put into place to dissuade the practice of writing fraudulent checks.

This democratization of payments, albeit limited to men of at least some means, meant that even men of modest means were incentivized to deposit their money. It wasn’t for security or earning interest, as you might think, but for the “convenience of an effective means of making payment.”21 Checks, much like today, powered local commerce.

As merchant bankers began opening trading houses in multiple cities, these practices spread to other hubs of commerce. The most important of these hubs for our story is the Dutch Lowlands, what we’d now call the Netherlands. Here, Renaissance checks received their last great transformation to become the modern check: negotiability.

Negotiability & multi-step settlement

Up until now, the payment instruments have required that the person collecting the payment go directly to (or at least through a direct representative of) the party who was to pay the bill/cash the check. This works fine if there’s only one bank or when the size of the network is small — thus allowing trust to be maintained. Where it breaks down is when the payer is not readily available.

To permit these kinds of transactions, checks — or rather the liability for payment of checks — needed to be able to be transferred to other parties. Historians Stephen Quinn and William Roberds call this “negotiability” and said it was “the single most important development in the history of the check”.22

If a check had negotiability, it could be converted to cash with someone other than the final party — often for a discount to the face amount or a nominal fee. These bonds were trusted because of the inclusion of a “bearer clause.” Such a clause allowed for the legal rights of collection to be transferred to a party other than the one listed. (Side note: Checks today are still convertible, and it’s why check cashing is a $20.5 billion industry in the U.S.23)

Below is a note from 1565 issued by Jan Spierinck which includes such a bearer clause24:

I, Jan Spierinck, confess and declare by my own hand to owe the honourable Lord Coenraerdt Schetz the sum of four hundred pounds Flemish groat and this on the account of the equal sum I have received from him to my satisfaction. I promise to fully pay the afore-mentioned Lord Coenraerdt Schetz or the bearer hereof on the fourth day of the coming month of August without any delay, committing my person and all my possessions now and in the future. In the year 1565 11 June

[Signature of Jan Spierinck]

Once again, we can rearrange the message to see:

How much currency is changing hands: 400 pounds Flemish Groat (a type of coin)

Where the currency coming from / who is paying (debtor): Jan Spierinck

Where the currency is going to / who is receiving the payment (creditor): Lord Coenraerdt Schetz or whomever presents the note on August 4th, 1565

A form of authorization: Jan Spierinck’s signature

What it’s for: A loan from Lord Coenraerdt Schetz

Two points of note that make this almost a modern check, but not quite, is that it still has that usance period — in this case the 54 days between June 11 and August 4, 1565 — and that its redeemable only with Jan and not with his banker (assuming he had one).

Notes like this were prevalent in the Low Country throughout the 16th century and would often change hands multiple times before being settled. Sometimes the bills never settled at all and began functioning as a de facto paper currency because people so trusted the payer of the bill to honor the debt if presented.

As the volume of these notes and checks increased, trading these bills became a market in and of itself. If you trusted the person who wrote the note (and the one selling it to you), then you’d buy it at or near the face value — 400 groat in the example above. If, however, you knew it was from an untrustworthy source or didn’t trust the drawee to pay, you might buy it at a low price before turning around to quickly unload the note on an unsuspecting acquaintance.

This led to a messy century where checks had a long chain of endorsers and settlement could take weeks, even months!

The ambiguity also opened a door for fraud and bad, “dishonored” checks to trade in the market leading to several disruptions and scandals.

Frustration with this situation led to the 1609 founding of a municipal bank in Amsterdam to facilitate the settlement of bills of exchange, foreshadowing what would become an important role for the Federal Reserve three centuries later. All bills payable in Amsterdam were required to be settled through the municipal bank, a requirement that limited the indefinite circulation of bills and led to more efficient and predictable settlement cycles.25

Money & Macro has a good video on the development of central banking and a section on the founding of the Bank of Amsterdam if you’re interested.

This centralized settling increased the speed of the transactions and ultimately increased trust in the system. With increased trust, came increased use and paved the way for several financial innovations which made the Netherlands one of the richest nations of the 16th and 17th centuries. The success and wealth attracted the attention, the envy even, of their neighbors across the English Channel.

The Glorious Revolution as Financial Revolution

In late 1688, a group of English elites invited William the Stadholder of the Netherlands and Mary Stuart, the daughter of King James II [of England], to invade England. They did so and deposed the king in a relatively bloodless revolution that dramatically recast the political, economic, and religious future [of England and the Netherlands]. William and Mary’s invasion of England and accession to the throne has traditionally been called the Glorious Revolution.

One crucial key to the invitation was a group of influential London merchants who were envious of the Dutch economic success and displeased with the economic policies of James II. As a result, they invited William to invade and supported his invasion in hopes of bringing his economic policies to Britain26

Five years after this invitation, these merchants received their wish. In 1693 the Bank of England (BoE) was chartered and shortly after began issuing banknotes — paper currency which could be redeemed on demand at the central bank, but only the central bank in London, for coins. The monopoly on bank notes, typically in high denominations, meant that most transactions instead continued to rely on checks for conducting trade.27

One of the imports that did not make it to England, at least not initially, was a centralized check clearing entity like the one we looked at in 1600s Amsterdam. Rather than a centralized agency, bankers would dispatch clerks to travel between the various banking houses and settle checks. This process was time consuming — and in part a reason for banking districts being so compact — and led to uncertainty about available balances. Much like the fed-up merchants of Amsterdam nearly two centuries earlier, the volume of payments via check in London banks became so great that in 1773 a group of London banks formed the London Clearing House.

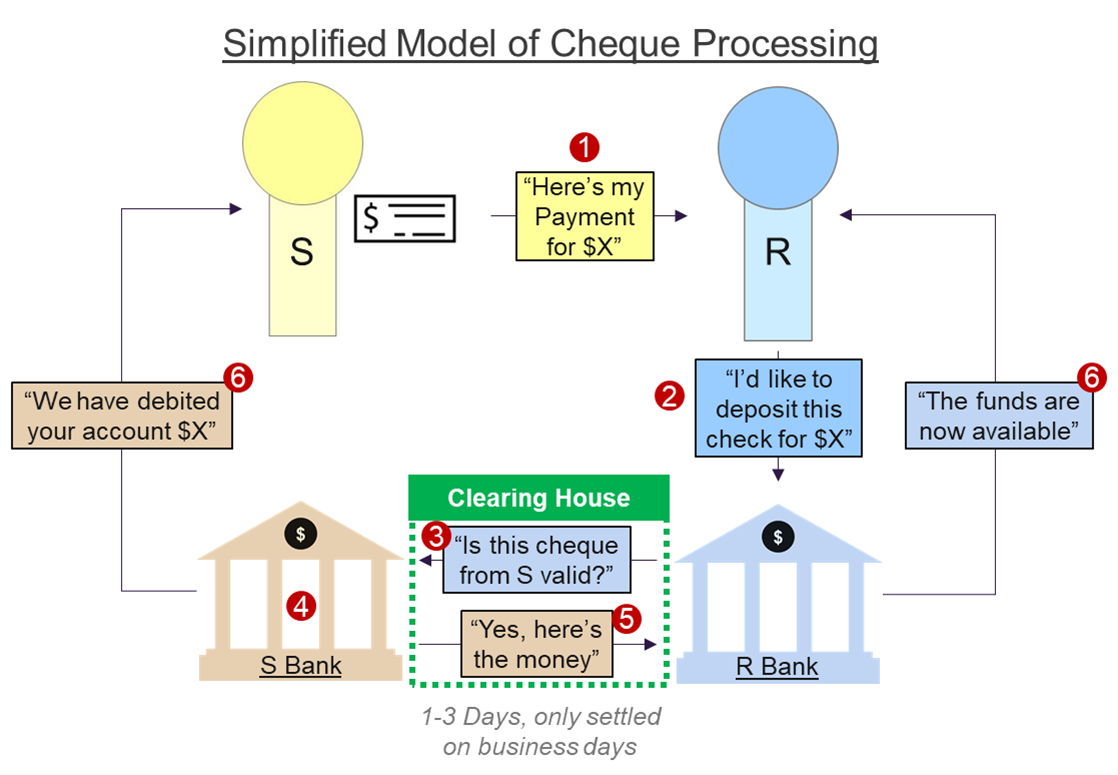

What is a clearing house?

‘Clearing’ is defined here as the process of calculating amounts due to and from each bank, confirming these amounts, and checking that funds are available for settlement. ‘Settlement’ is the transfer of funds; this extinguishes banks’ obligations.28

The London Clearing House served three key roles:

Simplifying Clearing: By bringing all checks together in a centralized location, bankers could quickly calculate how much currency needed to be settled with the various other members of the association.

Speeding Settlement: through regular meetings (weekly and then daily, and netting, only moving the difference between the amount due and amount owed, the speed of settlement was increased, ultimately speeding commerce within the system.

Reducing Risk: eliminating the need for unnecessary currency movement decreased the physical risk of settlement. Accelerating the clearing and settlement reduced counterparty and credit risk.

By being made up of a group, or consortium, of banks, the London Clearing House engendered more trust than any single member bank. This is because the needs of all — settling & clearing — would be considered equally when making decisions and such decisions were often made by vote of all consortium members. In practice, however, while the needs were met equally, the decisions were often handed down by coalitions of the larger members.

After some time, it was decided to use the Bank of England as the “bank to the banks” which prevented the need for holding funds in individual bank vaults. This had the effect of speeding payments ever faster: no more moving bullion, simply moving ink from one page to the next. The other consequence was that the group was now beholden to the regulations of a central authority over which they had no direct control.

It is around this same time that the American colonies experienced similar sentiments about their rule by an entity in which they had no representation.

Later in the 1800s, clearing houses in London absorbed some of the duties of correspondent banks, allowing for easier interregional check settlement. This last feature would play an important role in the highly fragmented banking culture in the U.S. later in the century.

America’s early history with banks and their checks

America was the earliest beneficiary of British financial innovations, but with a distinctly individualist and decentralized spin befitting its revolutionary founding. The U.S. was founded on ideals of liberty and freedom from what was seen as “oppressive” central authorities29 — like, say, the BoE. This is distaste for authority in finance was most evident in the failure of the First (1791 to 1811) and Second National Bank (1817-1837).

A lack of a strong central authority led to an era of “Free Banking” from 1837 to 1863 where bank were subject to loose state regulations, no national regulator, and were able to issue their own currency — think of the Amsterdam checking system but with banks and at a continental scale.30 Even with the elimination of state currencies in 1863, their replacement, checks, fared little better as they relied on long, complicated, and expensive correspondent banking networks to settle and clear.

The founding and subsequent failure of hundreds of banks across the US eroded what little trust the nation had in regional, let alone national, financial systems. If your bank note or check wasn’t worth what was stated, then why trust anything other than hard coins? The penultimate innovation before we explore the founding of ACH was the solution for this exact problem.

American clearing houses

I should note that the clearing houses of America we modeled on those in Europe and grew out of similar circumstances. In fact, the story in America is nearly a century behind the United Kingdom which was itself centuries behind the Netherlands and Italy. America is exceptional in several ways, but innovation in the world of finance rarely happens on the periphery. Look towards the middle of the 20th century for this side of the Atlantic to shine.

To combat this lack of trust, organizations like the New York Clearing House Association (now The Clearinghouse or TCH) were organized by banks beginning in the 1850s.3132 The 50 New York City banks which made up the Association saved clerks and porters hours of scurrying around the city, but balances still had to be settled in gold so at the end of each day, there was still a need for the physical movement of bullion.

Gary Gorton, a Fed Economist, explains the process in his 1984 article Private Clearinghouses and the Origins of Central Banking:

To improve the process of exchange further the clearinghouse issued specie certificates to replace gold in clearing balances at the clearinghouse. Each bank deposited gold with a designated clearinghouse member bank and received specie certificates to use in settling at the clearinghouse. The certificates were issued in large denominations and were used exclusively to replace gold coins in clearinghouse settlements. Gold was still used in clearinghouse settlements, but the certificates reduced the amount needed. In 1857 the specie certificates amounted to $6.5 million, and the daily exchanges to $20 million.

The clearinghouse system at this stage reduced the use of cash, removed the risk of transporting large amounts of gold through the streets, and minimized the costs of runners, porters, messengers, and bookkeepers. Clearings through the New York City Clearinghouse grew by leaps and bounds… By the 1880s clearinghouses dotted the American banking landscape.

This innovation — settling checks with, well, even bigger checks — is the transition point in our discussion. Where previously we were watching modern payment methods evolve, we now are watching the genesis of modern payment systems.

In the next post, we’ll meet our story’s protagonist and watch the system go digital.

This post is Eurocentric in the middle and focused almost exclusively on America at the end, I had to draw boundaries somewhere otherwise this thing would never be published. Remember that (1) the original impetus for this series was FedNow being launched by the US Federal Reserve and (2) I’m based in America (major home bias). That said, I will eventually get into what other countries around the world

Keynes, J. M. The Economic Journal, vol. 24, no. 95, 1914, pp. 419–21. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2222005. Accessed 10 June 2023.

One of the popular fallacies in connection with commerce is that in modern days a money-saving device has been introduced called credit and that, before this device was known, all, purchases were paid for in cash, in other words in coins. A careful investigation shows that the precise reverse is true. In olden days coins played a far smaller part in commerce than they do today. Indeed so small was the quantity of coins, that they did not even suffice for the needs of the [Medieval English] Royal household and estates which regularly used tokens of various kinds for the purpose of making small payments. So unimportant indeed was the coinage that sometimes Kings did not hesitate to call it all in for re-minting and re-issue and still commerce went on just the same.

For more on this line of reasoning please see “Chapter 3: The Myth of Barter” from David Graeber’s Debt.

Gojko Barjamovic et al, Trade, Merchants, and the Lost Cities of the Bronze Age, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 134, Issue 3, August 2019, Pages 1455–1503, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz009

James Wright, ed., INTERNATIONAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SOCIAL AND BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES, Elsevier, 2014

Fikri Kulakoğlu & Güzel Öztürk. 2015. New evidence for international trade in Bronze Age central Anatolia: recently discovered bullae at Kültepe-Kanesh. Antiquity Project Gallery 89(343): http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/kulakoglu343

The timeline of non-Muslim kingdoms roughly works out to Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Seleucids, Romans, Parthians, and Byzantines.

Quinn, Stephen; Roberds, William (2008) : The evolution of the check as a means of payment: A historical survey, Economic Review, ISSN 0732-1813, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA, Vol. 93

Ashtor, Eliahu. 1972. Banking instruments between the Muslim East and the Christian West. Journal of European Economic History 1:553–73.

al-Tabari, Bosworth, C.E.; The History of al-Ṭabarī Vol. 30, The 'Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium: The Caliphates of Musa al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid A.D. 785-809/A.H. 169-193; pg. 106

Oran, Ahmad & Khaznakatbi, Khaida’. (2009). The Economic System under the Abbasids Dynasty. The Encyclopedia of Islamic Economics. 2. 257-266.

I make this distinction precise as the East of Europe was still controlled by the Byzantine Romans. The Byzantines were aware of the suftajah and its value (and necessity) in facilitating long-distance trade. The Western Empire, mired by internal squabbles and incursions from non-Latins, was too preoccupied to provide the stability needed for such trade.

Malaysian Shariah Advisory Council; Resolutions of the Securities Commission Shariah Advisory Council, pg 32-34

“Prosperous and successful crime goes by the name of virtue; good men obey the bad, might is right and fear oppresses law.” Seneca, The Madness of Hercules, lines 251-253 (Amphitryon)

Mueller, Reinhold C. The Venetian Money Market: Banks, Panics, and the Public Debt, 1200-1500. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.68456. Pg. 637

This is where money changers and merchant bankers were able to side step usury laws and generate profit (or compensate themselves for the risk undertaken, depending on your preferred view of businesses). If you offered an exchange rate which was greater than the true rate, then the buyer of the currency — the one presenting the bill of exchange, the drawer — would pay the spread which becomes profit for the merchant banker.

A licit transaction in bills (there are also illicit transactions that we will consider later) must always begin with the completed performance of a transaction in goods. So let us imagine a situation in which there are two merchants: Albert is a merchant in London engaged in the export of wool, and Bernard is a merchant in Antwerp who is importing the wool. Bernard is in receipt of a shipment of wool from Albert which has not yet been paid for, with the result that Bernard owes Albert money. To put it in a way that is more useful for our purposes (i.e. to put it the “right way around”), we might say that Albert holds balances abroad, with Bernard, as a result of a prior non-financial transaction. This fact gives Albert the opportunity to “draw on” these foreign balances by “drawing” a bill “on” Bernard in Antwerp, which means that Albert is the “drawer” and Bernard is the “drawee.” Understanding this allows us to clear up one source of confusion: “drawing” refers not to the “drawing up” of the bill as a piece of writing, but rather to “drawing on” foreign balances in the way that one “draws on” a resource (this usage survives in modern banking when we speak of a check that is “drawn on” a deposit account).

In order to do this, it is likely (though not strictly necessary) that Albert will engage the services of an exchange banker. He will go to Lombard Street, which is called that because that’s the place where you can find the Italians who are engaged in the business of exchange banking. Albert’s goal is to transform his “absent money” (funds that he holds with Bernard in Antwerp) into “present money” (English coins in his pocket in London) and the Italian firms can help him do this in virtue of the fact that they have a network of branch offices in all of the major exchange centers. At Lombard Street, Albert will find bidders for the purchase of his bill drawn on Bernard: the exchange bankers will compete with one another to offer to pay Albert cash in exchange for his bill, by which he instructs Bernard to “pay” the balance owed him to the Antwerp correspondent of the London exchange banker. Thus, Bernard, the “drawee,” is also the “payer,” and the “payee” is the Antwerp partner of the London exchange banker who purchases or “takes” the bill, after which he will “remit” the bill by ship to the Antwerp partner, who will then “deliver” the bill to Bernard, the drawee and payer, who must then either “protest” or “accept” the bill.

If the bill is “protested,” it becomes a matter of litigation between the various parties (and possibly leading to a souring of the business relationship between Albert and Bernard). Thus, the bills of exchange are not anonymous instruments, and gathering the information required to assess the creditworthiness of Albert and Bernard would be essential to the business of the exchange bankers. But if the bill is “accepted” by Bernard upon delivery, then this means that he has both accepted his liability to Albert (has acknowledged that Albert does in fact hold balances with him) and has confirmed his intention to pay the bill upon maturity, at the conclusion of the period of usance. The bill of exchange, in other words, is not a demand instrument: upon being presented with the bill, Bernard has additional time to raise the funds to pay the bill (perhaps one or two months), and this period of time, the “usance,” is the period of time for which charging a price would constitute “usury.”

The usance isn’t a novel idea in global trade, in fact, the traders of the Middle East had been using time limited w.r.t. suftajah for centuries. What’s really interesting, and explored a little bit later, is the fact that a person could redeem the note at an earlier date for a small sum of money. That is, they were practicing the time-value-of-money calculations that everyone who’s taken an account course has learned — without the fancy calculators of course.

Milinski Manfred 2016Reputation, a universal currency for human social interactionsPhil. Trans. R. Soc. B3712015010020150100, http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0100, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2015.0100

“Reputation is a strong driver of cooperation, serving as a currency for future social exchange”

Spallanzani, Marco. 1978. A note on Florentine banking in the Renaissance: Orders of payment and cheques. Journal of Economic History 7, no. 1:145–68.

Spallanzani (1978), pg. 164

Quinn & Roberds (2008), pg. 5

https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-statistics/market-size/check-cashing-payday-loan-services-united-states

Puttevils, J. (2015). Tweaking financial instruments: Bills obligatory in sixteenth-century Antwerp. Financial History Review, 22(3), 337-361. doi:10.1017/S0968565015000207

Quinn & Roberds (2008), pg. 6

Angle, John David, "Glorious Revolution as Financial Revolution" (2013). History Faculty Publications. 6. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_research/6

This is another example of network effects and policy driving unintended behaviors. By limiting bank notes to 50 pounds, which was a crazy high sum at the time, almost every transaction was left to function using coins, which were heavy and could be easily stolen, or checks. As more people began using checks, more people opened deposit accounts, which led to more people using checks. Gotta love flywheels.

Norman, Ben and Shaw, Rachel and Speight, George, The History of Interbank Settlement Arrangements: Exploring Central Banks’ Role in the Payment System (June 13, 2011). Bank of England Working Paper No. 412, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1863929 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1863929

The extended lack of central authority is part of the reason for the myriad of federal and state regulators in the US:

The primary federal regulator for

national banks and thrifts is the OCC, their chartering authority;

state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System is the Federal Reserve;

state-chartered thrifts and banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System is the FDIC;

foreign banks operating in the United States is the Fed or OCC, depending on the type;

credit unions—if federally chartered or federally insured—is the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), which administers a deposit insurance fund separate from the FDIC's.

National banks, state-chartered banks, and thrifts are also subject to the FDIC regulatory authority, because their deposits are covered by FDIC deposit insurance.

Additionally, though unrelated to the story: At the time the U.S. had a central currency in the U.S. Dollar, but the medium of exchange — the bank note — could be issued by any bank in the country. This led to situations where a note for $5 in Long Island, New York might only be worth $3 in Newark, New Jersey or $1 in New Orleans, Louisiana.

This all depended, just like with Renaissance checks, on how well respected or well known the issuer was in the area. As a general rule, the further away a bank, the great the discount there was on the note or check.

The practice of banks issuing notes also meant that those banks whose notes were less likely to be deposited had an incentive to issue more notes than they had in deposits. This cause numerous issues and blow-ups in regional financial systems.

All of this tomfoolery was put to an end with a series of acts

National Currency Act of 1863: Establishes a national currency (the dollar) and National banks

National Banking Act of 1864: Establishes the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC and introduces bank examinations

National Banking Act of 1865: levies a tax on state currency. The tax goes from 2 percent to 10 percent, resulting in the use of checks taking their place in interregional trade.

Gorton, Gary. “Clearinghouses and the Origin of Central Banking in the United States.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 45, no. 2, 1985, pp. 277–83.

As discussed earlier, such systems had already been well established in places like London since 1773 and the Netherlands since the 17th century. See Ecclesiastes 1:9.