Event Studies and the *Proof* for EMH | Finance Papers 1.4

The moment we've been building towards is here! Let's see how a salesman, computer programmer, and two PhD students worked to deliver empirical evidence for the efficient markets.

Fama’s 60+ years of impactful output began in 1965. Fama, however, was just getting started. The following 5 years saw a string of papers coming out of the University of Chicago and MIT, culminating in two classics of economics:

These papers helped catapult EMH from just another idea in the academic discourse to a fundamental and (for a time) universally acknowledge idea which has defined careers for generations of economists. Before this could happen, Fama would need to prove (or at least not disprove) that EMH was valid.

Enter the true hero of our story: the event study.

What is an event study?

Well, Richard Roll, one of the authors of the 1969 paper, provides a pretty clear answer during an interview with the Cal Tech Heritage Project:

An event study examines stocks that do the same thing, but at different points in time.

The “thing” that stocks do could be a dividend, merger/acquisition, stock split, CEO change, etc. Studying the event usually — but not always — examines how the price of a given stock changes in the weeks and months before and after the event. Roll continues:

But of course, if you look at a single stock, there are lots of other things going on, a lot of noise in the data. What you do in an event study is, you line up all these different stocks, find a sample of companies that have done the same thing …, and you line them up on the date of the [event]. And by doing that, you wash out all the noise of other things that happened to each stock so that you're left with only a pure measure of the [event].

Running these tests requires a lot of data on a lot of stocks — the 1969 paper covers 622 companies from 1926 to 1960. However, at the beginning of the 1960s no database of sufficient size and scope existed. Luckily a University of Chicago alumni was willing to fund such a database, but for a very different purpose.

The Man Who Brought Wall Street to Main Street

The dataset used by Fama and team was the brainchild of Business Week editor and Merrill-Lynch partner Louis Engel. A brilliant salesman, Engels always sought ways to bring value to his investing clients — his most famous work in this regard was a 6,450 word, full-page ad in the New York Times detailing the process for buying stocks.

In 1959, Engel had a “silly idea”: if you threw a dart at any given stock on the NYSE, what was the probability you could make money? After shopping the idea around and refining his question to “what’s the average rate of return on the market”, he reached out to his alma mater and came into contact with James Lorie, associate dean of the business school and professor of marketing.

Lorie assured Engel that they would “answer this question [of market return] better than it had been answered before for $50,000 in one year.”

“We spent $250,000 and took four years.”

— James Lorie

The Quant: Larry Fisher

Part of the reason the project ran so far over was because of the data — there wasn’t any that a machine could read. It was stored in printed tables, on exchange receipts, and in the filings of companies; and the information was messy: formats, naming conventions, and record quality varied between each stock and reporting period. It is no small thing to say that this task would require the brightest mind in data and statistics.

To accomplish the herculean effort of ingesting, cleaning, and analyzing what was, at the time, the most extensive financial database ever assembled, Lorie recruited Lawrence “Larry” Fisher to be associate director of the new Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP).

Fisher was naturally gifted in math — particularly logic and statistics — and was an accomplished coder. He wrote nearly every line of code from basic search functions to analysis and reporting tools. To quote Fama, “I still don’t know how [Larry Fisher] did it…he thought of everything that could possibly be relevant and [made] the data perfect.”

It was Fisher’s pioneering work in data analysis and quality control that allowed CRSP to be used to answer Fama, Jensen, and Roll’s later questions as well as the one that had started CRSP in the first place.

And the Answer Is…

In December, 1963, CRSP announced its findings in the Journal Of Business before Engels had the article re-published, again as a full page ad, in a January 1964 edition of New York Times under the title “Rates of Return on Investments in Common Stocks.”

To answer Engel’s original question: the market returned about 9.0% before taxes and between 6.8% and 8.2% after taxes (depending on your tax bracket). With nearly 60 years more data, the market return has continued to average about 7.0%.

Now CRSP had the ability to answer more problems, they just needed people to start asking them. Thankfully, two doctoral students were ready to (be told to) start asking some questions.

“Well, We Did Have Data on [Stock] Splits”

[After the 1964 publication,] Lorie became nervous. He said, ‘OK, Merrill Lynch gave us this massive amount of money [to build the CRSP database]…now we don’t know if anybody’s going to use it. So [Lorie] said, ‘Why don’t you do a study of stock splits’

A quick overview on stock splits: ‘Stock Splits’ are when a company chooses to increase the number of shares owned by an investor based on a specified ratio and the original number of shares owned. The ratio and reasons for a split are less important for our discussion (see Investopedia for a more detailed explanation), but what’s important to understand is that the total value of the company does not change, only the price per share.

If you had a company with 10 shares outstanding each worth $10 per share, then the total company value is $100. Suppose you decide to split your stock 2:1 — two shares for every one owned — then, all else equal, you’d have 20 shares which are each worth $5 and the company would still be worth $100.

At the time the paper was written, 1969, stock splits were “very often” linked to “substantial dividend increases.” This will become more important later in the post.

As the newly minted Professor Fama was teaching Chicago’s first finance course on Markowitz, he assigned a term paper on the topic to two PhD candidates: Michael Jensen and Richard Roll. So the two started digging in, not thinking anything of what was to come next.

“A Bug in the Code”

Jensen and Roll started by developing a stock price model, because if you’re going to measure the variation in expected return, you need to have a model for creating and forming those expectations. The two students leveraged their course studies under Fama to develop a market beta log-return model — a descendant of the one Sharpe had published in 1964.

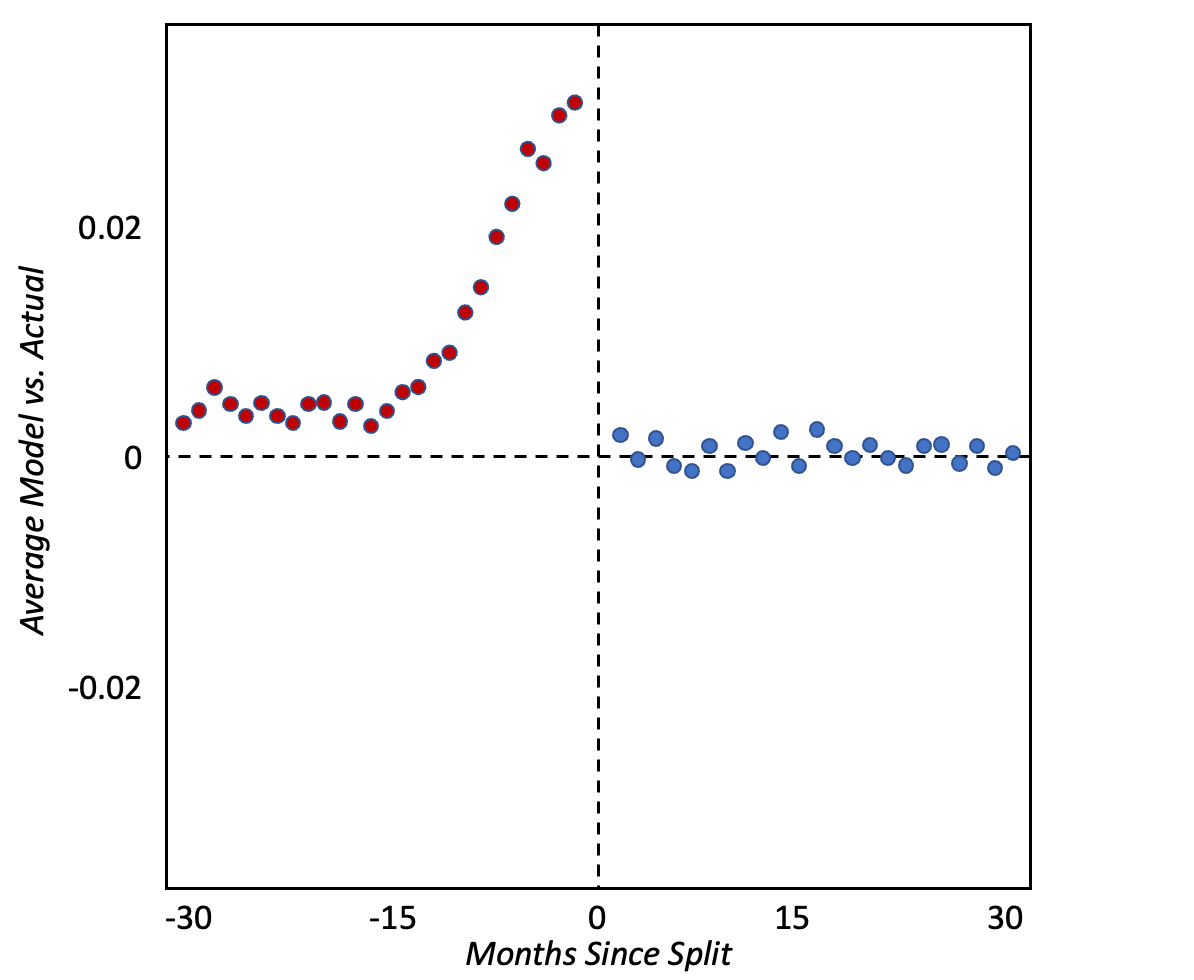

With a sufficient model in hand, Jensen and Roll got to work analyzing the CRSP data with the help of Fisher. They began by identifying 940 stock split events between 1926 and 1960. Because CRSP only had monthly return data and events, Jensen and Fisher applied their model to the 2.5 years (or 30 months) on either side of a stock split announcement date (month 0).

To “wash out all the noise of other things”, Jensen and Roll took the average of the resulting differences between expectation and reality and plotted it vs. the time relative to the stock split.

“This can’t be right”, they thought. “The plot is supposed to hover around zero, not spike in the months leading up to a split.”

The pair went back, checked their code, and plotted it again.

“Same result. Maybe there’s a bug in the code?”

Proof* for the EMH — FFJR (1969)

After the initial confusion, Jensen and Roll, with the help of Fama and Fisher, realized that they had just plotted some empirical evidence in support of the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

I’m going to quote their conclusion in full (emphasis is my own):

In sum, in the past stock splits have very often been associated with substantial dividend increases. The evidence indicates that the market realizes this and uses the announcement of a split to re-evaluate the stream of expected income from the shares.

Recall from the Markowitz post, that dividends are used to model the share price of a stock. If the dividends paid in the future are expected to be larger, then the share price should shift by a corresponding amount.

Moreover, the evidence indicates that on the average the market’s judgments concerning the information implications of a split are fully reflected in the price of a share at least by the end of the split month but most probably almost immediately after the announcement date. Thus, the results of the study lend considerable support to the conclusion that the stock market is “efficient” in the sense that stock prices adjust very rapidly to new information.

If the market is made up of rational actors with rational expectations about the future and equal access to the information, then they’ll all react the same way until the price reaches Bachelier’s “true price”.

The evidence suggests that in reacting to a split the market reacts only to its dividend implications. That is, the split causes price adjustments only to the extent that it is associated with changes in the anticipated level of future dividends.

This is most evident when looking at how the market treated companies which raised their dividend (the flat green series on the graph below) and how it reacted when companies did not increase or decreased dividends (shown in yellow on the graph below).

Finally, there seems to be no way to use a split to increase one’s expected returns, unless, of course, inside information concerning the split or subsequent dividend behavior is available.

A reminder of the definition of market efficiency for which we now have *proof*:

“In an efficient market … actual prices of individual securities already reflect the effects of information based both on events that have already occurred and on events which as of now the market expects to take place in the future.”

— Fama, 1965

Based on all the posts so far, it’s an open and shut case.

An investor can’t consistently outperform the market as all expectations of the future and available information are priced in immediately after the split is announced.

However, you might be left with a few nagging questions:

Why even bother investing actively if the market is efficient?

How can bubbles form if the market is efficient?

Here’s the thing: it’s not efficient…except for when it is.

There are a lot of opinions to unpack.

Sources & Additional Reading/Viewing

Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) History & Mission

Louis Engel

Richard Roll

The previous post in this three-part look at Fama’s Efficient Market Hypothesis

Here’s a preview of what’s coming up next…

“Pinpointing Where the Hypothesis Breaks Down”

To say that the Efficient Market Hypothesis is universally accepted is, to put it judiciously, hotly contested. To see what I mean, let’s check out what two of the 2013 winners of the Nobel prize — Eugene Fama and Robert Shiller — had to say about the EMH:

The evidence in support of the efficient markets model is extensive, and (somewhat uniquely in economics) contradictory evidence is sparse. — Fama, 1970

Economists look at the stock market, they see it going up and down, and usually they don’t have the foggiest notion why. They think they need an excuse, so they figured out a theory [the efficient market hypothesis] that excused them from not knowing. — Robert Shiller, 2013

We’ve spent the last 4 posts building the case for EMH up until 1970. There seems to be consensus so far, but like the early Christian Church, a single orthodox or catholic belief is only universal so long as everyone agrees on the priors. And as it turns out, not everyone was getting the same message from the published works…

Welcome to the [great] financial economics schism.

Extra Bits

It’s astonishing just how connected the financial economics community was to the University of Chicago in the 1960s…

“I've known Bill Sharpe longer than anybody else in the whole profession because I was a [MBA] student when he was an assistant professor [at the University of Washington].” — Richard Roll

I think what’s delightful in this interview of Fama by Roll is to see the smiles come to their faces as they recall their early days together and what it was like to be a pioneer in a field.

Engel’s full-page, all-text ad for Merrill-Lynch was titled “What Everybody Ought to Know about This Stock and Bond Business” and clocked it at 10 times the length of the average NYT article of 622 words. It provided a plain language and thorough explanation what a stock represented and a guide on how to trade them. The ad was so popular that readers asked for a book which resulted in the 1953 classic “How to Buy Stocks”