Pinpointing Where the Hypothesis Breaks Down | Finance Papers 1.5

Professional consensus can only hold for so long - about 9 years for the Efficient Markets Hypothesis. Let's see how our EMH story wraps up for Fama and witness the birth of Behavioral Economics.

To say that the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is universally accepted is, to put it judiciously, hotly contested. To see what I mean, let’s check out what two of the 2013 winners of the Nobel prize — Eugene Fama and Robert Shiller — had to say about the EMH:

The evidence in support of the efficient markets model is extensive, and (somewhat uniquely in economics) contradictory evidence is sparse. — Fama, 1970

Economists look at the stock market, they see it going up and down, and usually they don’t have the foggiest notion why. They think they need an excuse, so they figured out a theory [like the efficient market hypothesis] that excused them from not knowing. — Robert Shiller, 2013

Right then.

We’ve spent the last 4 posts building the case for EMH up until 1970. So far in our story, there seems to be consensus, but like the early Christian Church, a single orthodox or catholic belief is only universal so long as everyone agrees on the priors. And as it turns out, not everyone was getting the same message from the data…

Welcome to the [great] financial economics schism.

Re-Viewing the EMH

Like many schisms, the cracks in Financial Economics began when the early believers were brought together to reconcile their differences and establish a universally accepted doctrine. In the case of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, this reconciliation was undertaken by one man near the center of it all: Eugene Fama.

Riding of the wave of the 1969 event study paper, Fama began to collect the growing body of evidence for the Efficient Market Hypothesis in a review article. I call this out because everything discussed thus far in this series has been a research article.

The simplified distinction is that review articles summarize the current state of the research on topic while a research article presents new work and analysis on a particular facet of said topic. For those who need more, I’ve included a table highlighting some of the differences.

Fama’s second most-cited work fits the review article pattern well — walking through the foundational research chronologically before highlighting the recent papers and studies in support of EMH.

The main conclusions — what you and I are supposed to take away from the paper to proselytize to the masses — can be summarized as follows:

Markets exist to allocate resources and resources are allocated where they can generate the greatest return for a given investor’s risk tolerance.

Markets are considered “efficient” when prices “fully reflect all available information.”

There are 3 forms of the EMH which gradually relax the conditions of efficiency:

The strong-form does not relax the condition that ALL information is reflected in prices. “We do not expect [strong-form EMH] to be literally true.” It’s ‘an extreme view’ that doesn’t hold up to real-world tests and is ‘best viewed as a benchmark.’

Semi-strong-form only looks at the reaction of prices to public information. There is some robust evidence supporting this form — including FFJR (1969), Ball and Brown (1968), and Scholes (1969).

Weak-form EMH states that prices reflect past information and that the past information cannot be used as a reliable predictor of future returns. Fama spends 1/2 of the paper detailing voluminous weak-form research and supporting evidence.

Using the 3 forms of EMH detailed above, we are led to accept Semi-Strong Market Efficiency as the most likely form to be correct.

There is one point that I’m leaving out. It’s a gap that will end up becoming the chasm dividing the EMH believers. How do we know what the correct price is?

“Where the hypothesis breaks down”

It was clear from the beginning that the central question is whether asset prices reflect all available information…

This is the strong-form of EMH, and Fama has already admitted that this view is inconsistent with reality. But that’s ok for now, because the semi-strong-form — best exemplified in Fama, Fisher, Jensen, Roll (FFJR) the year prior — still holds up.

We can’t test whether the market does what it is supposed to do [reflect all information] unless we specify what it is supposed to do. …Tests of efficiency basically test whether the properties of expected returns implied by the assumed model of market equilibrium are observed in actual returns.

The market is “supposed to” conform to one of the asset pricing models — usually a model based on Sharpe’s CAPM — developed by economists. EMH proponents then use the expected returns generated by such models and compare them to the actual returns of the asset. If we don’t see a meaningful difference between the expected and actual returns, then we fail to reject that the market is efficient.

At the time, Fama wrote in 1970 that “[t]he evidence in support of the efficient markets model is extensive and (somewhat uniquely in economics) contradictory evidence is sparse.” At the time, Fama was correct…

However…

If the tests reject [the EMH], we don’t know whether the problem is an inefficient market or a bad model of market equilibrium. This is the joint hypothesis problem…

— Eugene Fama, 2013 Nobel Prize Lecture

And there it is. In one sentence, Fama, here with over 40 years of hindsight, spells out the issue. To put it more plainly:

In efficient markets, the difference between modeled and actual returns should be zero.

The return models assume that markets are made up of rational investors.

The sum of all rational investors is assumed to create an efficient market.

…wait…

How did this happen?

To find the source of this logic loop, we’ll need to briefly return to the past and look at a patriarch of financial economics: Simon Kuznets.

To quote one writer in 1985:

When Kuznets began his work … it could rightly be said that economics was a speculative discipline. ... This method had yielded moderately useful results for our understanding of relative prices and the allocation of resources among markets. It was, however, almost helpless in matters concerned with the aggregative behavior of economies, their growth and fluctuations. To deal with these aspects of economic life, economics had to change from being a branch of applied logic into an empirical science. … We owe this change as much—or more—to Kuznets's achievements and leadership as to those of any other single scholar in our time.

But why does Kuznets matter to our story? Well, besides inventing the equation for GDP, he taught Milton Friedman at Columbia University.

Friedman would go on to teach Harry Markowitz, Eugene Fama, and many more at the University of Chicago from 1946 to his retirement in 1977. To keep track of all the names and relationships, I’ve included a graphic to follow along.

Kuznets stressed the importance of empiricism — being able to test a hypothesis against real world data — in economics. This was a lesson that Friedman took to heart and stressed to his students (among many other things at the Chicago School).

Markowitz’s doctoral advisor was Friedman, who by then was a fellow of the mathematically grounded “Econometric Society”. Again, recall that Markowitz was also heavily influenced by the members of the Cowles Commission, another empirically minded group, while writing his 1952 paper on the efficient frontier which would form the bedrock of CAPM and later EMH.

To create this frontier Markowitz made two key assumptions which now bring us us back to our story:

A (rational) investor clearly wants to select the portfolio with the maximum return and the minimum risk.

If the investor selects a portfolio with less correlated assets, the riskiness of the overall portfolio decreases.

“Anomalies”

After publication, economists became wrapped up in the “efficient markets revolution”, propelled mostly by Fama’s enthusiastic evangelizing. Economists had finally secured what the Cowles Commission and Econometrics Society had dreamed of: a comprehensive and testable model of finance.

The number of papers testing market efficiency ballooned in the 1970s — even Robert Shiller, Fama’s co-recipient of the 2013 Nobel and author of the scathing introductory quote, “was part of the movement then… with my Ph.D. dissertation (1972) about the efficiency of the long-term bond market.”

It was, to quote my conversation with economist Dr. Jeffrey Born, “a time period when reporting anything other than evidence in support of the EMH just did not happen in most of the highly regarded finance journals.”

Over the decade, however, economists began to publish about certain circumstances where market efficiency didn’t seem to hold. Rather than saying the hypothesis was false, authors opted for the more demure label of “anomaly.” The choice of the word revealing the bias reviewers and editors had in the day.

Toward the end of the decade and despite Fama’s best efforts, these anomalies had piled up to the point where they were no longer relegated to so called “B journals”, but came to the mainstream. By 1979 the literature was pointing out that these anomalies like small cap stocks out-performing and asset pricing bubbles seemed to defy the tenet that investors were rational.

So we reach the end and the “95 Theses” of our story: the 1979 publication of “Prospect theory: Analysis of decision under risk” by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. The paper was “a critique of expected utility theory” (the basis of Markowitz’s work which lies at the bedrock of modern finance).

Kahneman and Tversky, along with Richard Thaler and Robert Shiller, had kicked off the behavioral finance revolution which focused precisely on the ways that individuals were irrational and portfolios were more correlated than we believed.

So is the Efficient Market Hypothesis dead?

Not everyone was ready to throw out EMH, particular Fama. He has since gone on to incorporate the most notable of these anomalies into a new asset pricing model alongside Kenneth French in 1992 and 2014.

Fama’s also kept up a tremendous publishing pace, averaging about 2.4 papers per year across his nearly 60 year career. Most of the work, unsurprisingly focused on market efficiency and it’s continued role in our ever changing world.

Given all of this how does our protagonist think he’s done?

I don’t count papers, I count number of citations! — Eugene Fama, 2022

And if that’s the measuring stick of a successful idea, then I think Fama and his almost 350,000 citations have a pretty compelling case to make yet.

This concludes my first season (series?) of Finance Papers. Together we explored the history of modern finance from Markowitz’s bedrock 1952 paper on the efficient investment frontier, saw the application of the idea applied to create a William Sharpe’s capital asset pricing model (CAPM) a decade later, and watched it all come together as Eugene Fama, along with several of his students and colleagues, established the Efficient Market Hypothesis as one of the most important (and most controversial) ideas in all of modern finance.

The next series of Finance Papers will follow a familiar name as he goes from Fama’s star student to the master of management finance. Join me as we explore the Theory of the Firm.

Acknowledgements:

I couldn’t have completed this work without help from my copy editor (thanks Mom), creative sounding board, Thomas, and ever patient wife, Dana.

Thanks also go out to Dr. Jeffrey Born and Joeri Schasfoort, PhD. for direction on this topic. Several of my ideas also were influenced by blog posts from Beatrice Cherrier and Noah Smith.

Sources & Additional Reading/Viewing

“A Brief History of the Efficient Market Hypothesis”, Lecture by Eugene Fama (2008)

“Are markets efficient?” : A Debate between Richard Thaler and Eugene Fama (2016)

The previous posts in Fama’s series:

The excerpts are taken directly from the Nobel Prize lectures given by Eugene Fama & Robert Shiller. To view the lectures in their original forms, please see this link for Fama and this one for Shiller.

Aggregated Predictability of Global Anomalies, Mike Dong (2019)

“If Fama were Newton, would Shiller be Einstein?” by Noah Smith

Here’s a preview of what’s coming up next…

The Business of Business | Finance Papers 2.1

Businesses are made of individuals, each of whom work together to achieve a common goal. Maybe the goal is to create great products, to provide exceptional service, or create the next big thing.

Why do the products have to be great? Because they want to sell them.

Why does the service need to be exceptional? So that they’re chosen over others who offer such services.

Why create the big thing? Because there might be a way to monetize that attention.

The business of business — or better put the purpose of a corporation — as posited by many business professors “is to make money.”

This series of Financial Papers will follow the ideas of a familiar face through the history of corporate finance to discover whether money is really at the root after all.

Extra Bits

If you’re curious, 350,000 citations is a lot. Fama (1970) has over 37,000 citations. Per the journal Nature: ~45% of papers are never cited, and less than 1.8% are cited more than 100 times.

The “fair game” model of market efficiency which Samuelson and Mandelbrot identify relies on two key pillars:

1. Market equilibrium can be modeled as a function of expected returns

2. All information is fully utilized by a market and reflected in prices

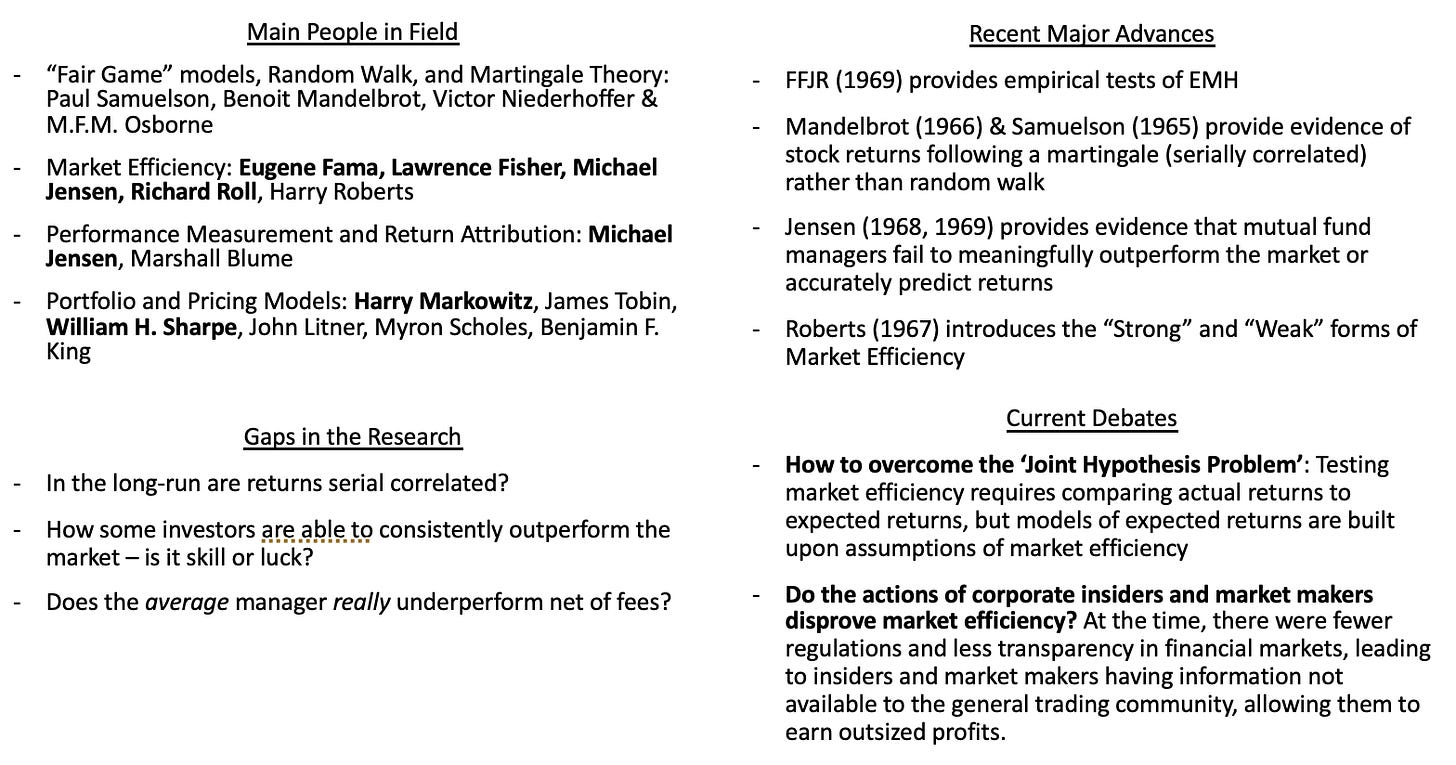

Astute readers may notice that this sounds familiar.I made a diagram of Fama 1970 paper using the framework proposed by UT Austin. Fama cites himself and his advancements a lot in this work — something that tends to happen when you’re pioneering — so I tried to focus more on the other authors in the space.

Friedman ended up with a teaching position at the University of Chicago precisely because of his mathematical rigor. You can read the correspondence about his hiring here.

“I think most of the time, most financial asset prices reflect what is public information. When we discover something that seems to stand apart, professional money tends to come in and make the so-called anomaly go away.”

— Dr. Jeffrey Born, Northeastern University

Fama didn’t take the breakup too well: “The behavioral finance literature is largely an attack on market efficiency…[it] has not put forth a full blown model for prices and returns that can be tested and potentially rejected.”