When we left off, we had arrived at the FedPayment Improvement project, the modern version of the Atlanta Payments Project, and teased the launch of RTP1, The Clearing House’s private sector solution for faster payments. This time, we’re looking at things as they are in the U.S.

Forcing the U.S. to catch up

Filling the digital gap was left to card networks and new entrants like PayPal. Smartphones added fuel to the fire by giving people anywhere instant access to the internet. This, along with developments internationally, was the environment in which Sandra Pianalto took the reigns of the Fed’s Financial Services Policy Committee (FSPC).

Pianalto, then President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, described the FSPC’s purpose in a 2012 speech: “The [FSPC] is responsible for the overall direction of financial services and related support functions for the Federal Reserve Banks, as well as for providing Federal Reserve leadership in dealing with the evolving U.S. payments system.”

After becoming chair, Pianalto took steps to adapt the Fed’s payment systems to meet the needs of the digital age. This included completing the updates laid out in the Check 21 Act2 as well as looking beyond inter-bank needs and towards “end-to-end” solutions.

In the same 2012 speech, Pianalto laid out the three objectives which would drive future growth and investment:

Move transactions faster from origination to settlement

Function more efficiently

Develop the array of payment instruments that satisfy consumer preferences

These were the bedrock of conversations which took place within the FSPC into the next year. In that time they produced the Payment System Improvement – Consultation Paper and launched the FedPayments Improvement Project.

On September 24, 2013, Pianalto stood before the crowd at the Payments Symposium hosted by the Chicago Fed. In the room were dozens of seasoned payments professionals from the Fed, banks, financial service providers, and industry. Here she announced the project that would culminate in FedNow.

She also stated, in no uncertain terms, that the Fed would take a leading role in guiding conversations.3 The crux of the issue being that the private market might not be able to handle the task alone, because faster payments didn’t have enough demand. Her counter was that “[t]he new electronic payment channels [like ACH] created their own demand.”

The Fed would work with industry to create the faster networks, because innovative systems need a push from an entity willing to shoulder years of slow growth. This is why the Fed subsidized ACH across it’s first decade.

In 2013, Pianalto urged participants not to ask “How will most payments be made in the U.S. 20 years from now?” but instead “How should most payments be made?”

Though Pianalto departed in 2014, the FedPayments Improvement Project summarized their initial findings in the 2013 Payment System Improvement – Consultation Paper which Pianalto presented. These ideas were further refined in Strategies for Improving the U.S. Payment System (2015) and expanded in Federal Reserve Next Steps in the Payments Improvement Journey (2017). The key points from all three are detailed below:

Internal Systems

The fractured U.S. financial system causes any industry led solution to face extreme difficulties on the road to ubiquity.

While market forces drive demand, payment innovation in the U.S. tends to require a large central authority (the Fed, mega-cap bank) to push the market.

Same-Day ACH clearing and settlement can be leveraged while a true real-time system is developed.

External Examples

“The decision to launch a faster payments system has been primarily strategic, not grounded in detailed, positive business cases; most countries have relied on collective action and mandates to implement infrastructure improvements.”

Initial use is typically found in P2P, then B2B follows, and finally C2B + B2C transactions begin in earnest.

“All countries studied relied on a combination of incentives (e.g., additional revenue streams from value added services), disincentives and (threatened) regulation or mandates to drive financial institution and

end-user adoption.”

Faster Cross-Border Payments

Cross-border transactions with the U.S. are slow, opaque, and cumbersome.

Adopting the international payment standard, ISO 20022, is required for any U.S. system to seamlessly integrate in the world financial network.

Connecting to the world can be done through existing networks like SWIFT GPI and FedACH Global or through direct integration with other nation’s cross-border networks (see the recent example from India and Singapore).

The 2013 effort kicked off the race to build a real-time network in the U.S. The results have been a temporary bridge for the existing system — Same-Day ACH, a new P2P rail that simulates real-time payments from Early Warning Services (EWS), and two truly real-time rails in the form of RTP from The Clearing House (TCH) in 2017 and FedNow in 2023.

The Band-Aid

ACH, little more than electronically generated checking instructions, had two handicaps preventing it from being Dr. Lipis’ dream of a POS transaction service: Clearing & Settlement. As a reminder of what we’re talking about:

‘Clearing’ is defined here as the process of calculating amounts due to and from each bank, confirming these amounts, and checking that funds are available for settlement.

‘Settlement’ is the transfer of funds; this extinguishes banks’ obligations

For ACH, clearing is done in batches like physical clearinghouses of old and the settlement is typically done overnight. This leaves ACH payments taking 1-2 business days to settle, and in a world where checks might take a week or more to clear, ACH was gargantuan leap forward. However, in a world where PayPal and cards could have transactions settled in minutes, this wouldn’t be good enough.

To address the shortcomings of ACH while a true real-time network was developed, TCH’s electronic payments network (EPN), the private sector counterpart to FedACH, began trialing Same-Day clearing and settlement of ACH transactions in 2017.4

What makes Same-Day ACH attractive is that the file remains the same as it has been: fixed width text files with standardized forms. All that needed to change to make it same-day was how a bank processed the file. This could be done by changing the payment code within the ACH file.

While this made ACH faster, it did not make it real-time.

It retained the batch processing of old, but now there were 3 same-day processing and settlement windows. While it improved speed, the funds aren’t settled and available (useable by the receiver) until at least 3 hours after they’ve been sent. Additionally, it only functions during normal5 banking hours (no weekends or holidays). Despite the Fed joining in on Same-Day ACH in 2020, further driving ubiquity, it’s still limited to the limitation of its parent rail.

This rules out Same-Day ACH as a method for making most POS or real-time P2P transactions. As a result, the market looked elsewhere to fill this gap.

Zelle: Your Parent’s CashApp

Zelle is a real-time P2P money transfer app that now moves more money than fintech competitors CashApp and Venmo…combined.6

Zelle began life as clearXchange — the joint venture between JP Morgan, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America — in 2011. It was the brainchild of Michael Kennedy (Wells Fargo), David Owen (Bank of America), and Jack Stephenson (JP Morgan Chase) and represented big banking’s answer to the popular PayPal.

“We want our customers to be able to easily send money to anyone without having to establish a new account outside their primary bank. All our customers need to know is the email address or mobile number of a friend or family member and we will take care of the rest utilizing clearXchange.” — Michael Kennedy in a 2011 press release

The idea was to link bank accounts directly using people’s names and phone number or email — what we’d now call a ‘token’. This would make sending money simple, fast, and relatively secure for a bank’s customers. It also helped banks retain those customers by completely bypassing the loading/unloading of a digital wallet.

It was the early days of the consumer FinTech renaissance, but clearXchange struggled to gain acceptance despite being an early pioneer in the space and it’s sizable backing. The main hindrances for clearXchange were its lack of ubiquity (only a dozen banks ever signed on), the fact that it was owned by the largest U.S. banks, and its clunky, desktop-only UI. (see examples from Grant Thomas below)

Due to slow adoption, unlike their Australian counterparts, the owner banks looked to sell off clearXchange in 2015. The next year, the member banks sold clearXchange to Early Warning Services (EWS) owned by (unsurprisingly) the member banks along with PNC and SunTrust (now Truist).

EWS took a year to revamp the product and overhaul the brand before launching Zelle online and on mobile in 2017. The launch came with some fanfare, but it lacked the hype of CashApp and Venmo.7 Due to this, Zelle was destined to be used primarily by users who regularly visit their bank’s branches or online portal.

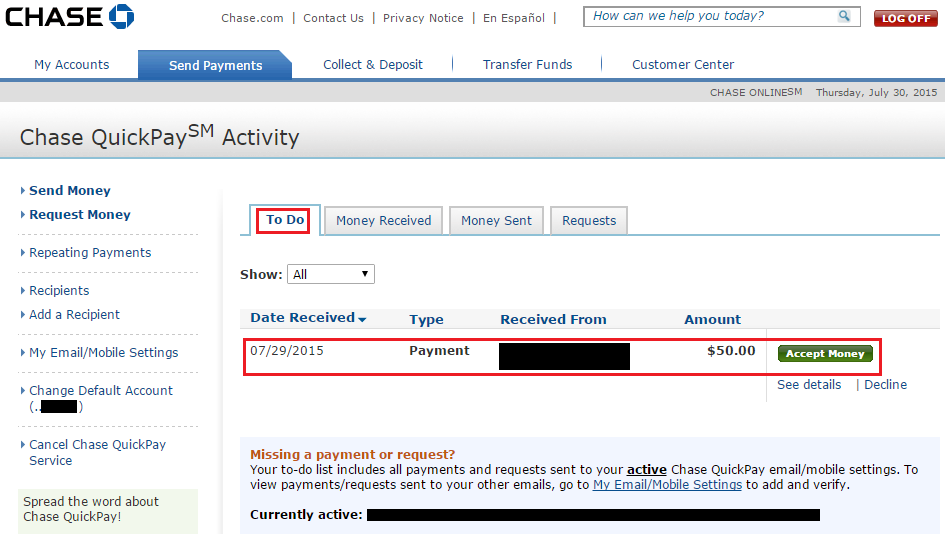

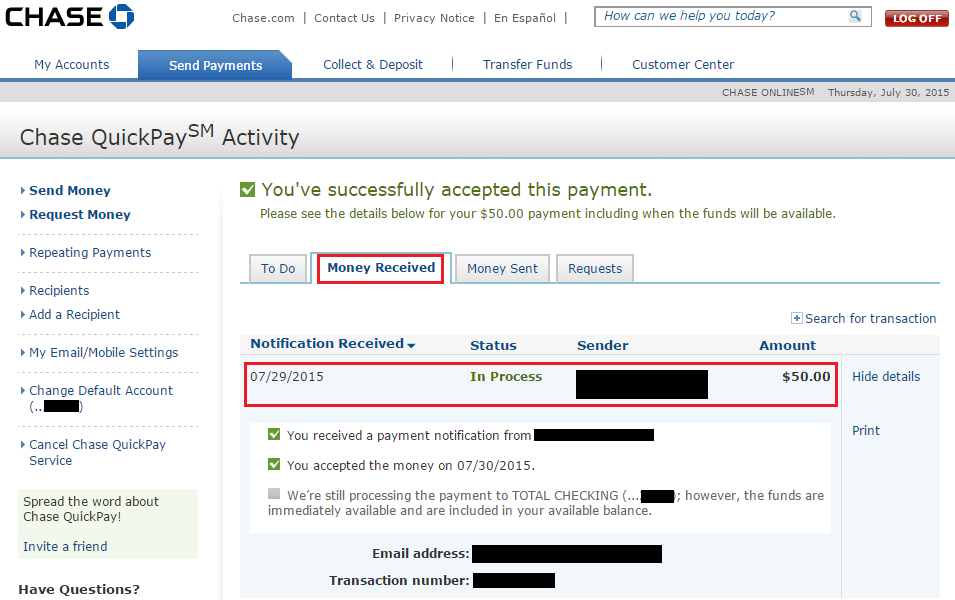

What made Zelle interesting was that the funds were available to the receiver instantly: there wasn’t a waiting period or a requirement to transfer funds out of the app and into their bank account. There are limits on daily and monthly transaction volumes. The latter restriction is to prevent people from operating business accounts without paying fees. But the former exists for a much more important reason — Zelle doesn’t settle in real-time.8

This is what keeps Zelle from being a payment rail. The clearing is handled within the system, but the funds are still settled through traditional rails like ACH and Wire.9

TCH’s RTP is meant to address the issues along with those faced by Same-Day ACH.

RTP

RTP (Real-Time Payments) is a 24/7, real-time clearing and settlement network operated by TCH (The Clearing House). Launched in 2017, four years after the Fed’s kickoff, the network represented the first truly new payments rail in more than 40 years.

In words which echo the launch of ACH, RTP was hailed as a leap forward for the U.S. and a chance to further increase the speed of commerce.

“As an industry, RTP positions us like never before to meet the evolving needs of our customers and commercial clients,” said William S. Demchak, PNC's chairman, president and chief executive officer and chairman of The Clearing House‘s Supervisory Board. “At a time when our clients are asking for the ability to conduct their business with greater speed, efficiency and security, RTP will make everyday financial tasks such as paying bills, issuing invoices, making payroll or settling insurance claims faster, safer and more satisfying for businesses and consumers across the country.”

RTP began development in 2015 after a joint-venture between VocaLink and TCH was announced. VocaLink (a subsidiary of MasterCard) was the mastermind behind the UK’s Faster Payments Scheme (which it delivered in just three years) and Singapore’s FAST payment scheme (which took only two years).

Like the systems in the UK and Singapore, TCH’s RTP is built to ISO 20022 standards. This means it can, in theory, be integrated with other networks like the ones previously mentioned and in places like Japan, South Korea, and India. This opens the door for the U.S. to continue its dominance in international trade and counteract currency rivals like China.

Being built on the new ISO 20022 standard also meant that most U.S. finance professionals and their accounting platforms were not familiar with the file format. This has required fintechs, banks, and accounting platforms to spend much of their time educating customers on what RTP is let alone how to use it.

Familiarity notwithstanding, it has proven difficult to find scalable use-cases for the platform or convince businesses that RTP is worth using vs. Same-Day ACH or wire. And just like Zelle, small financial institutions have been hesitant to join the network because of the influence of big banks and the fact that RTP cost more than an ACH and has lower transaction limits than a wire. All of this has combined to create a network which barely clears 300 million transactions a year compared to ACH’s 60 billion.10

This is where FedNow is meant to solve things.

FedNow

Announced August 5, 2019 by Fed Governor Lael Brainard (a member of the FSPC) and launched July 20, 2023, FedNow is the public market counterpart to TCH’s RTP. It’s built on the ISO 20022 file format and represents the U.S. government’s commitment to joining the rest of the world in real-time transactions. While there’s certainly going to be a lot of hype over the launch, the Fed is expecting more of a turtle than a hare in this race.

If everything goes to plan, FedNow will follow a similar route as ACH with low initial volumes and adoption followed by a slow and steady climb to ubiquity. At some point in that journey, the Fed will turn on the incentives (and disincentives) for members to begin using the platform.

The network is likely to see greater adoption compared to RTP as smaller banks have been hesitant to come under the hegemony of TCH (again, owned by the largest banks in the US). What remains to be seen is whether existing rails will lose volume or if the payments pie will simply grow larger as a result of a new rail. Only time will tell.

To end where we began, I’ll quote Pianalto’s 2013 speech::

The challenge for the industry is to provide a payment system for the future that combines the valued attributes of legacy payment methods – convenience, safety, and universal reach at low cost to the end user – with new technology that enables faster processing, enhanced convenience, and the extraction and use of valuable information that accompanies payments.

…

We have done it before and I know we will do it again.

The next, and final post will explore the world as it should be along with the implications of a real-time future.

If you want to get caught up on this series check out my previous posts:

If you want some other perspectives, check out this explainer on real-time payments in the U.S. from Jared Franklin.

I’ve written about Real-Time Payments (RTP) before, so I apologize to those of you who’ve taken the time to read my thoughts on this before. Hopefully you find that time, research, and experience have sharpened my thoughts (or at minimum my writing skills).

Many of the changes and refinement in my thinking, which I’ll get to in future posts, come from conversations I’ve had with friends and colleagues as well as doing all the research required for the previous posts in this particular series.

For more on the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act (“Check 21”), check out this breakdown from the Federal Reserve. In short, the 2004 act gave solid legal standing to digital copies of physical checks. This eliminated the need for checks to be delivered in order to be paid. The Fed used this act to invest in digital payments infrastructure and cut costs by closing dozens of check processing centers around the country.

The switch wasn’t without some negative side-effects, chiefly cutting 5,000 jobs in the midst of a recession.

At a glance, this collective approach might seem contrary to the thrust of history. Innovation in the US payments system has mainly been driven by the individual, entrepreneurial activity of banks, vendors, processors, and nonbank service providers. They respond to customer demand in a fiercely competitive environment. It is safe to say that American businesses and consumers derive great benefit from this competition in the form of diverse options and lower costs.

There have been times, however, when individual action on the part of banks, vendors, and nonbank service providers was not sufficient to move the payments system forward. Collective action was needed to implement MICR technology; to establish the ACH, card and ATM networks; and to implement Check 21. Collaboration will be necessary to continue to improve the US payments system.

“In Pursuit of a Better Payments System”, speech by Sandra Pianalto on September 24, 2013.

Theoretically, this feature could’ve gone live at any time, but there was no real demand from the market or push from the government. The whole system just required member banks to agree to the clearing and settlement terms.

They extended the windows by a few hours to allow for more flexibility.

This was driven by two primary factors:

It only covered about 60% of deposit accounts, meaning that many small banks were (and still are) excluded from participating in the closed network.

It required a bank account. There was no way to use the service if you didn’t have an account with one of the member banks. So the vast swathes of Americans who are under- or unbanked were left out of the service.

Even though Zelle is a network owned by large banks and directly linked to other banks, there is still the element of trust and counterparty risk. The receiving bank doesn’t want to be on the hook should the funds be recalled or made unavailable between the transaction date and the settlement date (usually end of the business day). There’s also the concern of a sending bank seeing large accounts move all their funds to another bank overnight not to mention fraud risks.

There’s also an immense amount of hesitation and skepticism for small banks joining in on anything EWS or TCH related, because the two consortiums are owned by the country’s largest banks. The smaller regional and community banks are wary of getting swept up and pushed around by the “big kids in the sandbox.”

I don’t want to spoil the narrative, but it’s important to note that certain member banks do settle Zelle transactions via RTP. For most banks, real-time settlement just isn’t necessary. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Proponents of the network will point to the 8 years of growth before the UK’s system reached 1B payments per year. However, it’s been nearly 6 years, and the system is just short of 300MM transactions per year.